Preparing for the 2022 KS2 Reading SATs: unpicking challenge in non-fiction texts

Helping children to flex their comprehension muscles on the best texts we can find - those that not only delight, amaze, and intrigue but that align well with the challenge featured in the test – will ensure that the knowledge and skills pupils have honed throughout their primary years are applied confidently during the timed test. Getting the pitch right therefore is key.

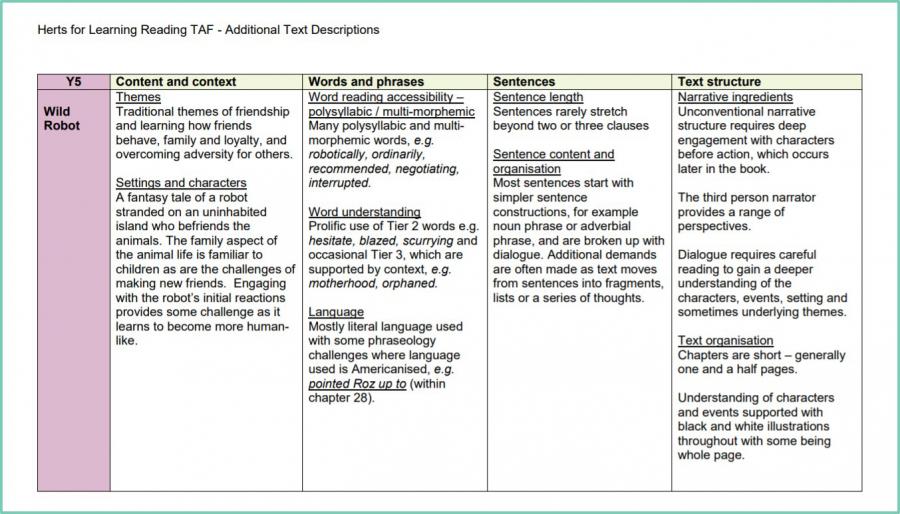

Selecting fiction texts in line with ARE has been helped by the publication of HFL Education’s Assessing with Age-Related Texts (AART) document. This is a unique reading assessment resource illustrating what ‘age-relatedness’ looks like at the end of years 3-6, as children move beyond book bands and reading schemes. Many teachers are finding this resource invaluable in helping them to refine their understanding of what constitutes a well-pitched fiction text for year groups across KS2.

You can find further details, including a video that explores this document, as well as others exploring the wider HFL Education KS1-KS2 Reading Tooolkit.

This blog is designed to complement this existing resource by offering an insight into the challenge presented by differing types of non-fiction texts.

By analysing the non-fiction texts that have featured in KS2 Reading SATs past papers, teachers can begin to build up a holistic understanding of the level of challenge presented in the test. Armed with this knowledge, teachers can engage pupils with texts of comparable complexity in the lead up to the SATs providing them with ample practise of tackling similar challenge in advance of the test day.

The KS2 Reading SATs consists of 3 texts comprising a range of fiction, non-fiction and poetry – although not all appear every year and not in that order. The texts are designed to move from most accessible (text 1) to most challenging (text 3). Since 2016 (when the test became more demanding), the past papers have featured a non-fiction text in positions 1-3, thus enabling an exploration of each text to gain an understanding of the features that constitute increasing challenge, according to the Standards & Testing Agency.

What follows is an analysis of the non-fiction texts that have featured in SATs papers from 2016 to 2019. Teachers should use this analysis to cross reference with the texts they are exploring with their pupils in the run-up to the KS2 SATs. In order to prepare pupils effectively for the KS2 reading test, it is helpful if children have encountered and explored - to varying degrees as appropriate - texts that contain many, if not all, of the features identified.

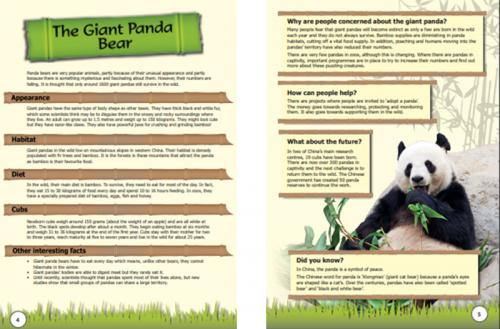

The Giant Panda Bear (2018)

Text position 1 – most accessible pitch

Features of the text:

- fairly standard, prototypical text type - non chronological report;

- consistent use of simple present tense throughout;

- simple sub-headings clearly indicate the content of the paragraph, including the use of single-word headings e.g. ‘Appearance’, ‘Habitat’, ‘Diet’;

- short paragraphs – approx. 4-5 sentences per paragraph;

- majority of sentences begin with the noun relating to the main subject of the text e.g. ‘the panda’ or use of a pronoun (they) in its place;

- some limited use of fronted adverbials to start sentences e.g. ‘In the wild, their main diet is bamboo.’

- most sentences follow a predicable pattern e.g. noun + verb + complement (Giant pandas have…/ Panda bears are…/Newborn cubs weigh…)

- greater reliance on coordinating conjunctions rather than subordinating conjunctions (limited range of subordinating conjunctions used e.g. where, which, as because).

Swimming the English Channel (2017)

Text position 2 – middle challenge pitch

Features of the text:

- mixed text type: biography; recount; Q & As; report;

- large chunks of text with limited use of subheadings to introduce new topics/sections;

- increasing variety of sentence constructions: 55% percent of sentences begin with a noun: most other sentences begin with a fronted adverbial e.g. ‘Nearly twenty-seven hours later…’/’In fact…’/’It must be said…’;

- some use of figurative/literary language e.g. idioms, metaphor and simile (the lone swimmer);

- cohesion is created through synonymous references to the same subject, moving beyond the simple use of the main noun or pronoun e.g. the lone swimmer/the exhausted man.

Fact Sheet: About Bumblebees (2019)

Text position 2 – middle challenge pitch

Features of the text:

- mixed text type: report; persuasion; explanation;

- attempt at humouring the reader e.g. ‘Bumblebees will never interrupt your picnic or steal your sandwiches!’

- sub-headings break up the text but vary in construction e.g. questions; commands; noun phrases (Save our bees/ Did you know that bumblebees have smelly feet?/ Buzz Pollination);

- some use of figurative/literary language e.g. idioms, metaphor and simile (a lifeline/ Don’t bee confused)

- widening range of subordinating conjunctions used to extend sentences (e.g. because, that, which, so, when, if);

- cohesion is created through several synonymous references to the same subject, moving beyond the simple use of the main noun or pronoun e.g. bumblebees/fat, furry little creatures/hardworking pollinators.

The Way of the Dodo (2016)

Text position 3 – most challenging pitch

Features of the text:

- no sub-headings;

- use of a variety of sentence constructions: only 40% percent of sentences begin with a noun/pronoun;

- regular use of long, complex sentence constructions: 50% of sentences contain 3 or more clauses;

- limited use of coordinating conjunctions; reliance on use of subordinating conjunctions (45% coordinating conjunctions; 55% subordinating conjunctions)

- considerable use of literary language e.g. idioms, metaphor and simile (easy pickings/ slipped into the pages/ wiped out/ in a new light/ offered themselves up/ brought its fate upon itself);

- increased use of nominalisation (turning verbs or adjectives into nouns or noun phrases) used frequently throughout the piece e.g. disappearance, thirst, suffocation, discovery, indication.

In summary, the most accessible text is a prototypical example of a commonly encountered text type (non-chronological report). This is the sort of reading material often planned into the Year 2 curriculum (and regularly revisited thereafter), with pupils given multiple opportunities to read reports about various topics, often animals, and write their own reports about a topic of choice. The sub-headings aid the reader through their clarity and relevance to the information grouped beneath. Within the most accessible text, the sentence structure is mainly predictable and repeated and most often follows a standard pattern: noun +verb +complement. There is some limited use of fronting clauses/adverbials before the main clause. Sometimes a sentence will begin with a pronoun rather than a noun but due to the limited range of subjects referred to within the piece, it is relatively easy for the reader to keep track of the topic/subject in question.

More challenging non-fiction texts can be characterised by less regular use of subheadings to guide the reader. Where sub-headings are used, they may vary in format, style and purpose. These texts often present a hybrid of text types. Sentence structure begins to vary in more challenging non-fiction texts. Sentences often begin with a fronted adverbial, meaning that key info is delayed which has an impact on the reader’s ability to grasp the topic until they have got some way through the sentence and discovered the subject. Cohesion is created within and across paragraphs through the increased use of connecting adverbs, as well as the use of synonymous references to the main subject, or subjects, within the piece. Synonymous references to the subject are often through extended noun phrases rather than single words e.g. fat, furry little creatures. The most notable difference between the most accessible text and more challenging non-fiction examples is in the increased use of literary language, specifically the inclusion of figurative language, including idioms and metaphors. The world of fiction and non-fiction writing collide in more challenging texts. Humour can also feature - in the text examples outlined above, this is evident with the inclusion of a pun (‘Don’t bee confused!’)

In the most challenging non-fiction texts, the average sentence length increases in line with the regular use of multi-clause sentences; the reader moves from one long sentence to another long sentence with little respite. Most notably, literary language is used liberally throughout the most challenging non-fiction texts to create detail, depth and imagery for the reader. Sub-headings are often omitted and readers have to work hard to summarise as they read, teasing out factual detail from often quite lengthy noun phrases. Cohesion is created across a number of paragraphs with multiple subjects being referred to in multiple ways forcing the reader to keep track of several concepts across the piece. Nominalisation – the process of changing verbs to nouns - is also a more prominent feature of the most challenging text. This grammatical process is a feature of academic writing and makes the text appear more formal. The use of repeated nominalisation can tire the reader as they must unravel the meaning of a single word that would, in an easier text, be expressed as a more accessible verb chain, using, most probably, a more commonly encountered verb e.g.

Original version from the 2016 text ‘The Way of the Dodo’:

‘The very fact that the dodo was still alive and well on Mauritius 4,000 years after a drought that claimed the lives of thousands of animals is an indication (noun) of the bird’s ability (noun) to survive.’

Amended version removing nominalisation:

The very fact that the dodo was still alive and well on Mauritius 4,000 years after a drought that claimed the lives of thousands of animals indicates/shows/demonstrates/proves (verb) that the bird’s was able to (verb chain) survive…harsh conditions’

Although nominalisation does feature in the more accessible texts, it is used less frequently. Of particular note is that even though nominalisation often reduces word count (a verb chain is reduced to a single word/or fewer words e.g. ‘was able to’ becomes ‘ability to’) the average sentence length remains high in the most challenging text (see below); this reaffirms the challenge that readers face when tackling the hardest texts – each sentence contains a great deal of information meaning that there is a lot for the reader to work through and retain. In summary, it is the combination of more challenging grammatical features, alongside their frequency, paired with the lack of navigational features, such as headings, that creates the cumulative challenge in the hardest non-fiction text presented in the KS2 Reading SATs test.

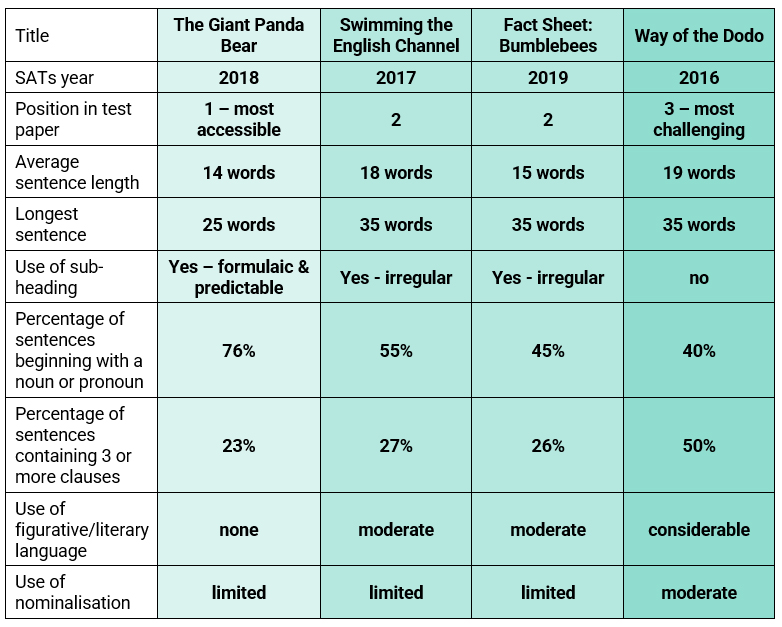

Quick comparison guide:

The intention of this guidance document is to support teachers to gain a clearer insight into what constitutes challenge in the non-fiction texts that have appeared as part of the KS2 Reading SATs since 2016.

For further support in preparing pupils for the KS2 Reading SATs, please do explore our linked blogs:

Reflections from analysis of the 2019 KS2 reading SATs: part 1

Reflections from analysis of the 2019 KS2 reading SATs: part 2

Reflections from analysis of the 2019 KS2 reading SATs: part 3

Reflections from analysis of the 2019 KS2 reading SATs: part 4