You have likely stumbled upon or explored Barak Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction. If not, we would recommend reading this superb article which was the first to comprehensively bring these principles to mainstream educators. It will undoubtedly resonate, and many of you will be saying to yourself, as we did, ‘I’m sure I already do plenty of this in my day to day classroom practice.’ It’s reassuring then, to know that these principles of instruction are built upon robust research:

‘research on how the mind acquires and uses information, the instructional procedures that are used by the most successful teachers, and the procedures invented by researchers to help students learn difficult tasks’.

When teaching reading and writing across the primary phase, we will find ourselves calling upon each of these 10 principles at various points within lessons and across sequences of lessons. Spelling does often come to mind though, when considering which aspect of the English curriculum relies more heavily on memory. When creating the ESSENTIALspelling scheme for Y2-Y6, we wanted to create something which explicitly drew upon what we now knew about effective instruction and learning, reflecting the insights of Rosenshine, and others. We wanted to come away from teaching children to memorise lists of words for spelling tests, and move towards teaching children to internalise and understand our spelling system, enabling them to build words from a knowledge of how to do so, rather than attempting to draw from a memorised list.

We wanted children to be able to apply this knowledge into their independent writing. Rosenshine states that, “Education involves helping a novice to develop strong, readily accessible background knowledge. It’s important that background knowledge be readily accessible, and this occurs when knowledge is well-rehearsed and tied to other knowledge.”

Tom Sherrington’s ‘Rosenshine’s Principles in Action’ is an extremely helpful publication, in which he explores each of the principles, providing useful examples. He states that ‘We organise information into schemata. Typically, new information is only stored if we can connect it to knowledge that we already have.’ So children need to access prior learning, not just for its own sake, but with the express intent of building upon that knowledge as a secure foundation.

For spelling instruction to be successful then, this idea must be harnessed; we must remind children of all that they know about a particular convention or phoneme, and build on that knowledge. For instance, when teaching children that the /dʒ/ phoneme is sometimes spelt dge in words like fudge, and dodge, we must first remind them that they already know that j spells /dʒ/ in jam and sometimes /dʒ/ is spelt with a g in words like giant and giraffe. Now we are carefully and deliberately building up a schema in the minds of the children, which will stick. Starting new learning from a point of drawing on existing knowledge also grows self-awareness, self-esteem and independence. ‘I knew more than I realised!’

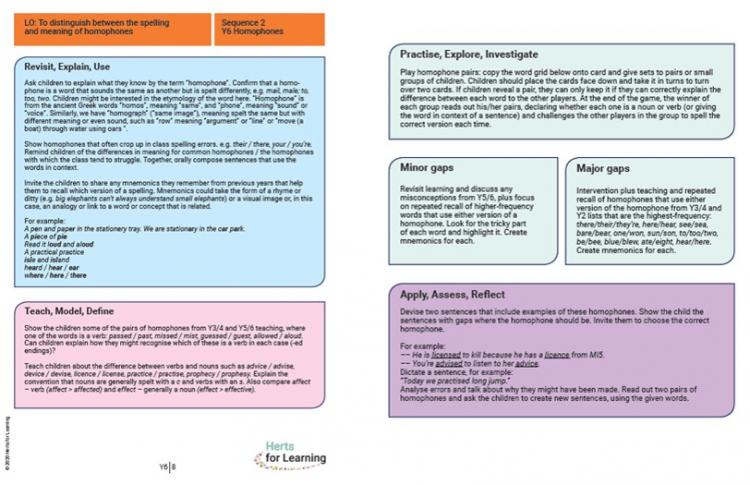

We will explore how each of Rosenshine’s Principles might be considered and applies when teaching spelling and its place in the widely used spelling sequence of Review, Teach, Practice and Apply, as illustrated in the screenshot of one of our ESSENTIALspelling plans here:

1. Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning: daily review can strengthen previous learning and can lead to fluent recall

Recall and review of previous learning can take various forms. A short sharp daily activity to memorise common exception words or high-frequency words that are commonly misspelt in our pupils’ books will grow automaticity and fluency with these words, which will eventually free up working memory.

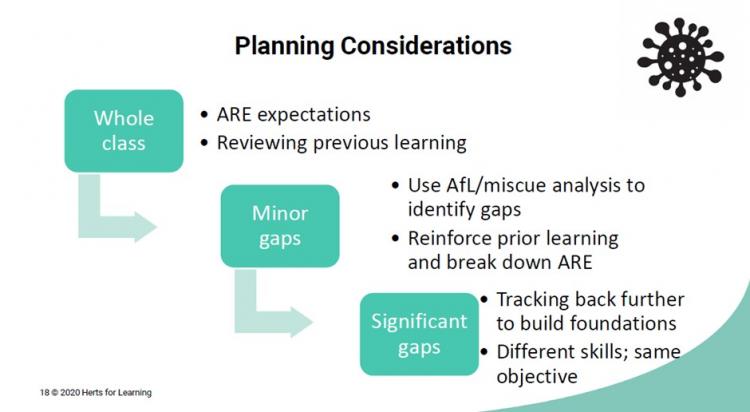

The National Curriculum 2014 spelling programme of study will be familiar to us all, but far too many spelling schemes do not appear to take account of the statement underneath each and every year group heading: Revision of work from … Therefore, schools and teachers dive into the programme of study for their year group without taking stock of what may need to be revised from the previous year groups. There is little point in teaching a child to spell ‘committee’ correctly, when we see ‘untill’ appearing in their independent writing repeatedly. It is important to pick the correct battles with that revision; we would suggest revisiting higher-stakes learning (words which appear most often in the English language and which are so often misspelt).

In year 3, for example, this revision might begin with the long vowel phonemes from key stage one. As they move into key stage two, children are often still selecting the correct phoneme, but choosing to represent it with the wrong grapheme. For instance, they might spell the word ‘flake’ flaik, or flayk. This is phonetically plausible but not orthographically correct. Using the ‘best bet’ approach can help with this common error. We could tell children that -ay is the best bet for the long at the end of a word, rarely in the middle; the split a_e is often found where the final sound in the word is a k. This is knowledge that they may well have been taught, but not retained. If we acknowledge that it is unreasonable for children to spelling patterns, rules or conventions from previous weeks, terms or years, then the principle of reviewing prior learning becomes an obvious necessity. Once we have embedded this into spelling instruction, we can at once assess children’s understanding and support children to bring spelling knowledge from their short term to long-term memory.

2. Present new material in short steps with student practice after each step: our working memory can only process a few bits of information at once

When introducing a new aspect of spelling, ensure children have a chance to digest key information that will help them build words in that pattern and allow them to try out your teaching points. For example in Y5 or 6, I might explain to children that they will be learning to add the suffix that sounds like ‘shul’ and means ‘relating to’. I might offer some words that end this way such as social, facial, residential and partial, and discuss the vocabulary with the class. Already that is quite a lot of information to process. So perhaps at this stage it might be better to practise linking words to meaning and getting used to reading and recognising these words before moving on. I would probably going on to explain how we might decide whether to spell the suffix as cial or tial. I need to look at the letter that precedes the suffix. What do children notice about the words social, facial, special or artificial? Hopefully, children will spot that these words have a vowel letter followed by the suffix cial. At this point, I might invite children to predict the endings for cru- and offi- and try to spell each word. Now I might add a new nugget of information and tell them that if the root of the word ends with a vowel letter, we normally add –cial and if the root ends with a consonant, we add tial. Alternatively, I might bring in a little of principle three:

3. Ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students

Here are a couple of questions relating to the above teaching sequence that might check understanding and encourage children to fire up connections in their minds to make the next step:

If the suffix is spelt –cial after a vowel letter, when do you think we might use the spelling –tial?

Can you tell me what the general rule for adding –tial might be?

Teachers are well versed in strategies to ensure all children are participating. A carefully structured question during a spelling sequence will offer valuable opportunities for assessment for learning. In this sequence, questions could include terminology checks such as:

- tell your partner what you understand by the terms root word, suffix, vowel and consonant

- on your whiteboard, record the word that you think means: ‘relating to the face’ and show me. Now show me the word that means ‘to do with society’.

- I will call out a word. Give me a thumbs up if you think it ends –cial and thumbs down if it ends with –tial.

- after three, I’d like you all to tell me which type of letter normally comes before the suffix –cial.

- can you summarise the two spelling conventions that you have learnt today?

Of course, every rule has words that break it and so convention is perhaps a more forgiving term when it comes to spelling. This sequence is no exception so another question you can ask students is: here are some words that don’t follow this pattern (such as financial), how might we remember this spelling? This kind of open-ended question opens up the floor to allow for children’s learning preferences to support them. Some might prefer to come up with a word mnemonic such as financial = cash and currency. Some might prefer visual prompts including colour blocking the suffix. Others yet might spot that there is a root word in there that also ends in a c- finance- and this is indeed another convention that holds true to other apparent ‘rule breakers’ such as the word commercial.

4. Provide models

This is an often-ignored teaching strategy when it comes to spelling instruction, but when included in the lesson can have a huge impact on children’s independence. Just as we might provide a running commentary as we construct a grammatically correct sentence, or explain our processing as we edit a piece of writing, we can offer children a model to apply to the construction of new words. Take the process of removing the final e from a root word before adding the suffix–ed. Articulating what you are thinking as you remove the e to avoid two es will enlighten the children who have missed the process behind the magical transformation of bake to baking for example. Furthermore, a visual model to accompany the commentary, provides a worked example that the children can emulate as they move to practise their own word building.

This form of cognitive support becomes vital as children attempt more complex spellings. Demonstrating how to break multisyllabic words up in order to spell them syllable by syllable, for example is a game-changer for less confident spellers. Rather than recording the word poisonous in one chunk, show children how you might begin by creating the first syllable pois, recognising that the diagraph oi appears in the middle of syllables, then we can add the next syllable ‘on’ and finally we add the suffix –ous which is regular in spelling. Pois/on/ous. Now model checking each syllable before moving on.

5. Guide student practice

Effective questioning is crucial for assessing student understanding during all stages of teaching, including while children are engaged in independent practice. A gentle hand on the tiller will guide and steer children towards a successful outcome and ensure the practice element of a spelling session is a worthwhile part of the learning sequence. As we stated earlier, breaking out of instruction mode to allow children to rehearse each new step is a valuable way of drip-feeding information in manageable chunks to avoid over-burdening the working memory. It also provides the children with a safe supported space in which to try out new skills and received instant feedback. They say ‘practice makes perfect’ but it can also serve to reinforce misconceptions. Keep in mind this maxim: ‘practice makes permanent’. If a child spells a word or set of words incorrectly during independent practice, they may well cement their errors and find it difficult to undo this mis-learning. Consider those high frequency words that appear throughout a piece of writing. A child whose spelling of ‘thay’ or ‘whith’ is left unchecked over the course of a lesson, a week or even a year, will have a lot of muscle memory to overturn before the correct spelling becomes habitual. Monitoring independent writing is a crucial part of guiding student practice: provide children with systematic feedback and support them to make corrections. When it comes to spelling, intervening can prevent the need for intervention.

6. Check for student understanding

By now, you’ll be seeing how these principles overlap and work harmoniously to ensure strong learning outcomes. We’ve discussed how the review part of a spelling sequence will be invaluable for reigniting past learning, firing up connections and assessing children’s understanding before they build the next layer of learning. Reviewing previous learning doesn’t mean, “Who can remember what we did last week or yesterday,” but is more about establishing what prior knowledge might be useful to today’s learning. Spelling accurately relies on so ensuring each piece of the puzzle fits together and thereby requires regular checking mechanisms along the way. Having established baseline understanding during the review part of a lesson, are the children still with you as you teach each next new step? Have you conferred with them whilst they move off for independent practice? And then as they begin to apply their knowledge and transfer skills, what level of understanding do they have now? Dictation is a useful way of checking whether the children have taken away a principle for spelling many words rather than a memory trick for one word. Going back to the example at the beginning of this blog, perhaps you have taught them that the grapheme dge appears at the end of a syllable and after a single vowel making a short vowel sound. You modelled words like fridge and budge. Can the children now apply that learning to spell bridge and fudge? What about badge or badger? Could children perhaps make up their own short sentences including any of the words they have been learning? The true testament of understanding is whether the pupil can explain what they now know about when to use this spelling pattern: discussion of learning is a fabulous way to check the child’s level of understanding. At this point, any misconceptions can be swiftly addressed and you can make a decision about where to take the learning next.

7. Obtain a high success rate during instruction

Rosenshine suggests that children need to achieve a high success rate during guided and independent practice, in order to have greater success when moving to application in a wider context: about 80% seems to show the correct balance between securing learning and being challenged. Instruction is not about trying to catch children out or providing tricky problem solving material, but instead requires stepping up the difficulty in small increments to ensure mastery of the taught material. If spelling practice does not have a high success rate, children could be reinforcing transcription errors, which they will apply in their independent writing. Furthermore, children who have fully grasped the teaching content will be better able to self-regulate and iron out any errors because they know why they went wrong. If teachers check children’s understanding along the way and adjust their content up or down to keep in line with this, then logically children’s success rate will be high.

8. Provide scaffolds for difficult tasks

Spelling is traditionally a discretely taught subject with a one size fits all approach. If children are deemed to be struggling with age-related spellings then they are often withdrawn from the lesson for an intervention rather than given ways to access the learning. Scaffolding in spelling can take a variety of forms to help the children access the learning:

- prompts such as: How could we break this word up into smaller chunks to help us spell it? What is the rule for adding this suffix to a word? Is there a rhyme that helps us to recall this word? What other words do you know that sound like this? What do we need to check when we’ve spelt a word like this?

- verbal modelling to help the children think through the process- the ‘expert’ might say: “When I write the plural of jelly I need to remember to take of the y and replace it with the letter i before adding es. Can you try that with the word welly?”

- physical scaffolds such as phoneme frames or the use of sound buttons under a word to help map it out, phoneme by phoneme. If the child struggles to transcribe words clearly, magnetic or foam letters can be arranged in the phoneme frame, thus reducing cognitive load needed for the task.

- reduce cognitive load by stripping back to one rule at a time. Instead of practising all the different rules for adding the suffix –ly, the child will focus on adding –ly to a word with no change to the root. Reduce cognitive load further by stripping back to root word to accommodate the child’s current level of confidence: add –ly to quick/ slow/ loud/soft rather than to word like natural or silent. If the child needs an even greater scaffold, that repetition with the change of one variable (such as the onset or rime of a single syllable word) can provide the support to get them started. For example: If I write the word spell rain, can you spell train, brain, main, drain, Spain?

- scaffolds could involve the ‘expert’ providing the unknown part of the word and allowing the child to building from there. For example, if the roots danger-, poison-, enorm-, jeal- are provided, can the child add the suffix –ous and then record the complete word in each case?

- paired practice takes no resourcing and is an effective way to scaffold learning.

As long as we don’t build too high, too fast, scaffolding provides the support a child needs to access the learning. This support can be withdrawn gradually as mastery of each step ensues.

9. Require and monitor independent practice

Rosenshine tells us ‘Students need extensive, successful, independent practice in order for skills and knowledge to become automatic’. In our experience, practice is often the aspect of spelling instruction which teachers and parents are often most comfortable with. How to make this meaningful and enjoyable then? We would like teachers, and in turn – parents, to be able to employ strategies beyond list making. When introducing a new convention, or reviewing a taught sound, we would suggest practising little and often, until it feels like overlearning in order for that target knowledge to be automatic. It also needs to be on the back of clear instruction. Children need first to understand how and why the word is built in the way that it is, and which other words fit that same convention, before practising it over and over. In our extensive scheme ESSENTIALspelling, we employ games and activities within the sequence, after the review and teaching aspects, such as bingo, use of the best bet approach, sorting sets of words, creating lists and tables, sentence writing, pattern exploration, and memory games for example. The activity will complement the learning to have the best impact. For instance, common exception words will suit a Kim’s Game type of game, whilst a revision of a long-vowel phoneme and its corresponding graphemes will suit a best-bet approach.

10. Weekly and monthly review to develop well-connected and automatic knowledge

Weekly and / or monthly review is something that we often see associated with spelling instruction. Again, there easy tweaks that can be made to increase not only the enjoyment of spelling testing, but also the efficacy of it. Dictations are known to be helpful in supporting children to see the words that they have been exploring in context, rather than in isolation. Asking children, in pairs, to look through their independent writing for errors and test each other back and forth, a word at a time and supporting each other with corrections can be most helpful to identify and fix common errors. Dropping previously taught words, perhaps common exception words, into dictations over time will support their retention. Pre-testing a spelling rule or convention with a list of words at the start of a sequence will not only provide valuable AfL, but will also allow a post-sequence test to give a clear indication of progress for each individual child. You could score the difference between their pre and post-test, rather than their score out of 10.

HFL Education's complete spelling scheme ESSENTIALspelling provides comprehensive lesson plans for Years 2-6 and is available to purchase.

ESSENTIALspelling draws on the principles outlined above. Revision of the previous year’s learning takes place at the start of each year, and in each sequence, prior knowledge is accessed and built upon. Differentiation and activities are built in, along with assessment and reflection opportunities.