RSHE – delivering quality puberty and sex education in primary years

It’s been ‘all change’ this year for most primary and junior schools in the delivery of puberty and sex education. Happily, gone is the far too long-lived ‘sex after SATs’ approach, with its visiting speaker coming in to deliver the gory truth in one terrifying fell swoop. The statutory RSHE curriculum demands that we prepare children in advance for the changes to come so that no child is unnecessarily frightened by the changes in their body. It has further supported the needs of children by clarifying that puberty education is not sex education, so children are now entitled to learn about their own body’s changes and cannot be removed by wary parents.

So how has it gone in your school this year? Teachers have been kept out of this content for so long that a considerable amount of insecurity and fear has developed around it. As a result, many schools have heavily relied on delivering the content of a purchased resource lock stock and puberty-barrel. If this has been your school’s experience, maybe it is now time to reflect and to build staff knowledge, confidence and ownership of the content and to form a better plan that tailors the lessons to your pupil’s needs ready for next year.

Many of the resources for delivering a comprehensive programme for RSHE that are on the market provide solidly good lessons (once you have livened them up a bit). However, puberty education tends to be the Achilles-heal for a great many of them. There is far too much focus on ‘this is preparing you for having children’, widely supported by biological diagrams that mean almost nothing to many children.

Puberty brings about bodily changes that are about maturing and becoming an adult. The physical changes come first, and the brain matures more slowly. In puberty the brain is suddenly awash with hormones that lead to all sorts of emotions, many of which can develop into overly-competitive and power-based approaches to relationships (the ‘pecking order of who is in and who is out). In which year do your hurtful or unkind incidents really start to ramp up?

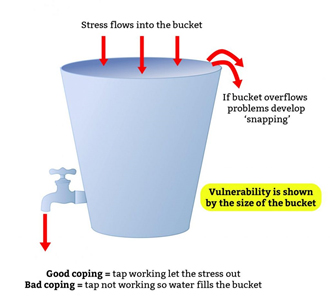

Puberty is a time when you start to experience inexplicable mood swings and emotions. So key learning has to involve understanding and managing moods and helping children to recognise that they must find a moral route through it all.

The devil is in the detail as the requirements emphasise that lessons need to be age- and/or stage-appropriate. Some seven year olds will be developing breasts and pubic hair whilst being quite emotionally and psychologically immature. Some children who have experienced trauma or abuse may be ready earlier than their peers for learning about sexuality and consent. A further group may already have an interest in or ‘assumed knowledge’ of sex through online experiences which are likely to be morally skewed.

So we must adapt our teaching to sufficiently meet the needs of children who are ahead of the curve, whilst maintaining an approach that gets rid of the separation of boys and girls and thus avoid any promotion of secrecy around puberty issues. A spiral curriculum approach, baselining and accessing pupil voice will be key to getting this right.

HFL Education’s Wellbeing Team have been supporting some schools already this summer on puberty and sex education. If we can support your staff team to be ready, confident and equipped for next year’s sex and puberty education, please contact us on wellbeing@hertsforlearning.co.uk.