Why is reading stories with children so important?

Storytelling is a fundamental element of being human, with childhood storytelling being the most prolific form, as it has been for generations. Stories were shared verbally long before the invention of the printing press after which the accessibility to written stories for all elements of society became the norm.

It is well understood that reading to children is vitally important, supporting the acquisition of language alongside social and emotional development.

So I thought I’d take some time to look a little more deeply into exactly why, scientifically, this is so.

Goldilocks and The Three Bears

My research into this took me to a blog from National Public Radio (NPR), written by Anya Kamenetz, an educational correspondent for the NPR and author of several educational books. She refers to a study that was presented to the Paediatric Academic Society in Canada in 2018. This research concerned the ‘Goldilocks Effect’ - such an apt name for research into reading with children in the Early Years. This research was led by Dr John Hutton. He describes differing types of storytelling as being rather like the porridge that Goldilocks stumbled across in the home of The Three Bears. The delivery of storytelling might be too hot for some, too cold for others but also, if we take care, might be ‘just right’ for many! This is described in more depth following Dr Hutton’s work at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital where some children aged four years were observed in an MRI scanner whilst being engaged in various styles of story sharing. This allowed their brain activity to be closely observed during the story sessions. The story sharing sessions included an audio-only version of a story, an illustrated storybook with audio and a cartoon version of a story. For those children engaged in an audio-only story, this appeared to be ‘too cold’, the language networks in their brains were active but there were definitely fewer brain connections being made overall. These children seemed to be ‘straining’ to understand the story. For those children who had animation only stories, there was much activity in the visual/audio perception centres of the brain but little was happening between other areas. The research team deduced that whilst the children’s understanding of language was helping them to keep up with the story that was being told, the animated pictures did the donkey work for the child, children’s ‘comprehension of the story’ was at its worst during this activity.

However, the illustrated book with an audio accompaniment being given simultaneously had the porridge that was ‘just right’! The children were paying attention to the words within a framework of understanding supported by the illustration. The most important factor of this ‘porridge’ is that the connections between all parts of the brain were heightened to include ‘visual perception, language, imagery and default mode’. For children who are aged 3-5 years, the last two areas generally mature at a later stage so these would not be developed at all by animation alone. Now, you may be wondering what the ‘default mode network’ (DMN) of the brain is? So was I! So I did some more research that I found to be very interesting indeed! Scientific evidence is still being gathered to support the DMN theory but this is becoming more robust as time goes on. It is an element of the brain that is most active when the brain is at rest and deactivates when the brain is involved in a task. Sections of the brain included in the DMN are areas that are involved with internal thought, memory, recognising thoughts and feelings in others, and the ‘posterior cingulate’ which is involved in the integration of internal thoughts. Scientists seem to have concluded that the DMN is used to enable us to daydream and retrieve memories. So you can see how this would impact on (and be impacted by) storytelling, using the imagination and making connections with personal experience to name but a few.

So as you can understand from this research, reading aloud to our children from an illustrated storybook is giving them the gift of exercising their brain and so much more is happening than we can actually see. Of course, this research was all undertaken within the confines of an MRI scanner, which most certainly excludes the additional emotional impact of warmth and physical closeness during the sharing of a story book.

But it might not be as simple as ‘just reading’

Something else that was not taken into account directly through the research was the dialogic elements of reading. This is not a word I’ve come across very regularly throughout my own teaching career but something I’ve heard mentioned more frequently in recent times. Dialogic reading, with our youngest children supports their understanding and expansion of aural language, as the adult helps the child to become a storyteller. It is very much about the adult reading with the child rather than to them. The adult takes the role of the listener, the questioner, the audience for the child. The ‘Reading Rockets’ website, tells us about the PEER sequence when sharing stories with children dialogically. The acronym stands for Prompting the child to talk about the book, Evaluating the response of the child, Expanding – reply by rewording and adding information and then Repeating the prompt to ensure the child has understood. An example of this could be when reading the aforementioned Goldilocks and the Three Bears…

Prompt from Adult: What’s this? (pointing to the Daddy bear’s chair)

Child: Chair

Adult: Yes, (Evaluating) it’s a big chair that belongs to Daddy Bear (Expanding). Can you say ‘Big Chair for Daddy Bear?’ (Repeats)

It is not recommended that that this happens on the very first reading of a book, but can take place on subsequent readings. The child must have the opportunity to just ‘drink in’ and absorb the story, simply enjoy the storytelling for its own worth, when first introduced to a book. Dialogic reading supports children in so many different ways, through developing skills in Communication and Language and oral language in particular. Children become more engaged with story books through these high quality interactions, adults are able to check a child’s understanding and discover where further support might be needed.

The key is to find really good story books where the illustrations are rich and closely follow the text. All the better if they are about something that interests the child or is a firm favourite that is chosen often.

Making reading fun!

In these times of social distancing and school closure, we have to find ways in which we can create opportunities to engage our children in high quality story sessions. Sharing stories online would model high quality reading of books to the adults who are caring for the children, disseminating good practice that will hopefully reach far beyond the current situation we have all found ourselves in. It’s so important that we keep children interested in books, keep them wanting to engage with reading whilst they aren’t having their daily dose or two (or three or four!) of story times with their friends in school. We can provide this online and also help parents to understand the importance of sharing story books, explaining the importance of sharing real books and not limiting the book-sharing to animated or other online book formats.

- provide an online story session through your school’s website or another electronic communication system that you have available.

- encourage adults to sit with the children whilst you read the story, helping them to answer questions and extending language

- set up a process to enable the children to choose the book for the next day as practitioners often do for self-registration. This might retain a sense of normality in our socially distant lives

- let the parents know in advance which books you will be sharing on which days. Parents can then read them beforehand with their children. The children will delight in knowing the story, anticipating what is coming next, the comfort of the familiarity and finding new things to look at or talk about.

- invite parents to make puppets for the characters, props and environments to support the storytelling in the children’s own homes

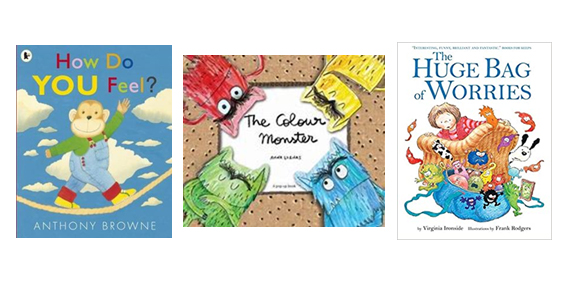

- choose some books that might support PSED, in particular emotional wellbeing – see some suggestions below

Some great examples are The Colour Monster by Anna Llenas published by Templar Publishing, The Huge bag of Worries by Virginia Ironside published by Hachette Children’s Group and How do you Feel by Anthony Browne published by Candlewick.

And not forgetting active phonics!

Then, of course, there is the other strand of reading which is about the children becoming independent readers, which is challenging to undertake remotely. One way that this could be supported is by the use of all of the Supersonic Phonics range of activity cards. These are perfect for parents to access at home to support phonic learning and will get the children active which is imperative during these times of restricted movement! Parents can purchase the cards online from the HfL shop and can use them digitally or print them if they are able. Most of the resources could be sourced very easily at home. You could guide parents as to which cards would be most appropriate for their child from the very early stages of Foundations for Phonics which are aimed at early Phase One learning, then Phases Two through to Five of the Supersonic Phonic range.

I hope you are still able to share stories with your Early Years children, perhaps in one of the ways described earlier in this blog. It’s one of the great pleasures of being an Early Years practitioner and we can’t underestimate the power of reading to our children!