You may remember reading various reports following the Covid pandemic that attempted to measure the impact on pupils’ learning, such as, Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 academic year. This was a fairly early one from the DfE which aimed to link outcomes in the first half of autumn term 2020/21 with outcomes at the same point in 2019/20 at pupil level and compare their progress with similar pupils in earlier academic years.

“We find that all year groups have experienced a learning loss in reading, ranging from 1.6 months to 2.0 months. The learning losses in mathematics were greater. In primary schools, learning losses averaged just over 3 months”.

Others reported similarly, including the EEF’s published findings from the longer term NFER study on the impact of the pandemic on younger pupils’ attainment. But if you ask colleagues teaching any year group, I think you are probably hearing the same as me, “We are still trying to get the learning back”.

In my advisory role, I work alongside many different teachers and their pupils. In more and more instances, I am being asked to help schools to address the fluency and language in children’s mathematics so that their reasoning can improve.

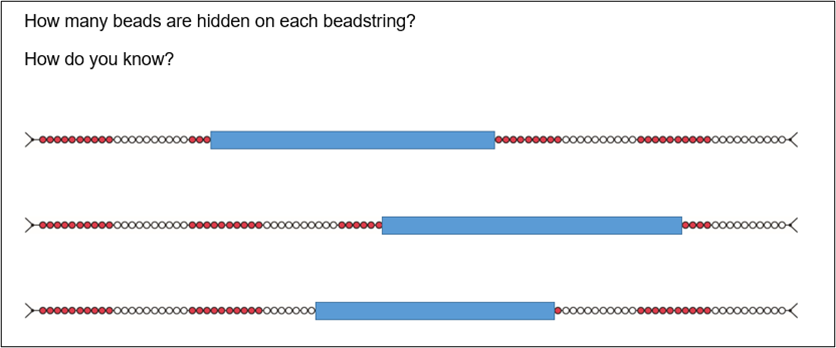

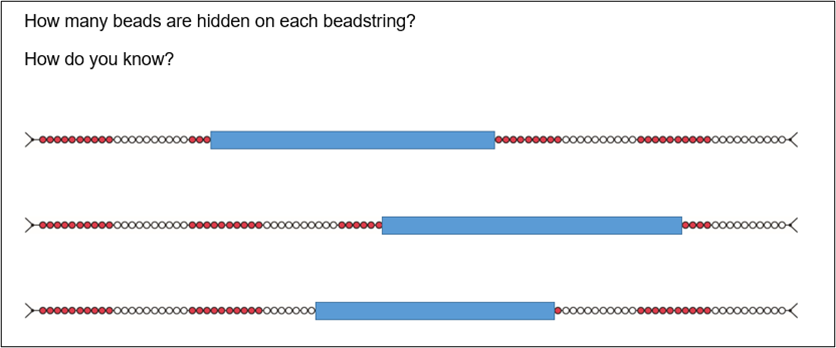

To support this, we’ve had a deep look at children’s approaches and tried to identify how we can make a difference. Using the broadest brush strokes, I can say that I have seen patterns. Younger children are not yet secure enough in their subitising skills to use them effectively to calculate with them. This limits them to their one-to-one counting strategies and returning to zero when asked to address number combinations.

Many older children are similarly constrained, identifying one value in any combination, and then counting on or back from there using their fingers. The repertoire of known facts does not seem to be progressing and the strategies to calculate more efficiently are almost absent.

So, does it matter if our children are using their fingers?

I recently read a research article to quench my own curiosity - “Development of number combination skill in the early school years: when do fingers help?” by Jordan, Kaplan, Ramineni and Locuniak (2008).

There has been much research to suggest that “along the path to mastery, fingers provide a natural scaffold for calculation”. There is even evidence that calculation skills were derived from finger sequencing in the first place!

I am sure you have recognised the propensity to use fingers to identify values and quantities in young children and this seems to be a very important start to “help children represent and manipulate quantities”. It becomes an important tool in their armoury to “facilitate the transition between early nonverbal representations and conventional symbolic representations”.

I think we can all agree that it is essential to our youngest learners (and can be celebrated) but, as the article goes on to explore, “There are questions, however, about the timing of finger use. When do children benefit from using their fingers and when do fingers potentially get in the way of development?”

From counting to calculating

Jordan et al carried out a longitudinal study of children, assessing confidence in number combinations for addition and subtraction and children’s approaches in Years 1, 2 and 3. They were specifically investigating whether they used their fingers to calculate the solution.

In Year One, the “frequency of finger use was a strong and reliable predictor of number combination accuracy.

By the end of Year 3, however, there was a small but significant negative correlation between finger use and accuracy... finger counting errors are more common on combinations with larger totals (e.g. > 10) (Gray and Tall, 1994)”.

So perhaps we are beginning to understand that whilst it’s a key element of early understanding of number, there is a point at which the reliance on counting, and using fingers, is prohibitive to efficient calculation and even accuracy. I think we would also agree that a child reliant on using fingers to calculate is not a fluent mathematician.

But what does a fluent mathematician look like?

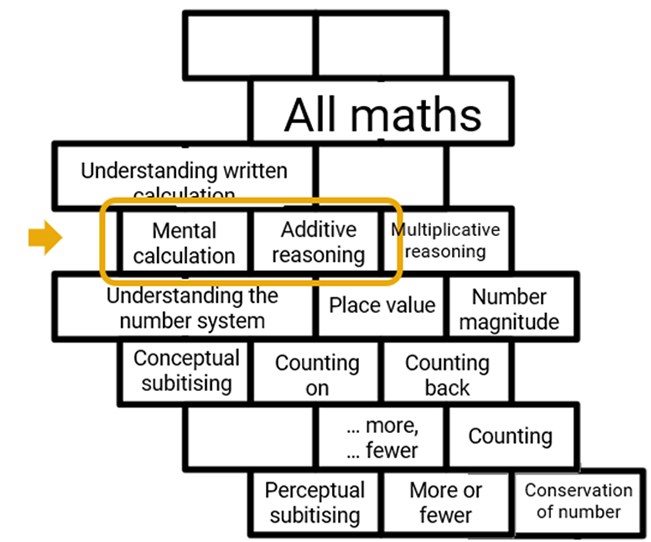

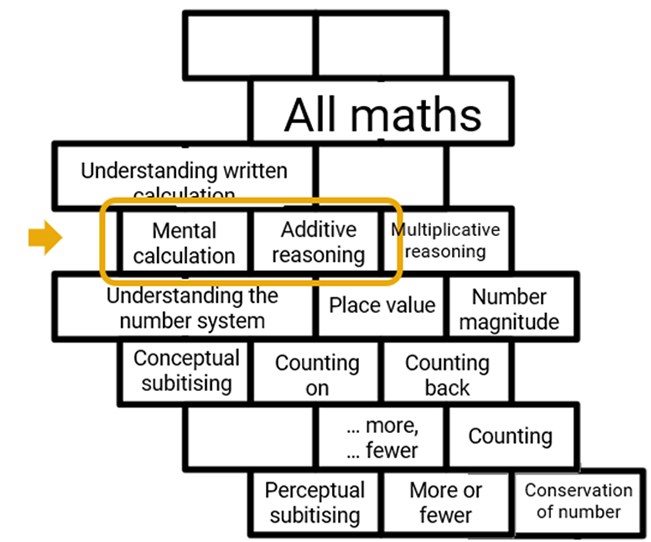

In “Mental Maths: Just About What We Do In Our Heads?”, Ineson and Babbar (2013) identify what we can call mental mathematics and its place in the curriculum. Interestingly, we did this as a team too, before we began to write the HFL Education ESSENTIALmaths resources and if you have taken part in our central training, you may remember one of our ‘four wise men’, Richard Skemp, who explored relational understanding in much detail, examining conceptual and procedural understanding in human thinking.

Ineson and Babbar explain his role in the debate.

“It is useful to draw on the distinction that Richard Skemp made between instrumental understanding of mathematics and relational understanding. He wrote about pupils developing an ‘instrumental’ understanding of mathematics where they follow ‘rules without reasons’ (Skemp, 1978). The alternative approach is to develop ‘relational’ understanding which encourages pupils to know both what to do with a calculation and why.”

They draw upon a useful analogy of a tourist in London, who uses just the underground system to get around town, compared to a London taxi driver setting out on the same journey. The tourist is fine to use the tube map, as long as the trains are all running, but the taxi driver would have alternative routes up their sleeve, responding to varied traffic conditions.

“The underground user is like the pupil with instrumental understanding; able to follow rules to go between different concepts within mathematics – for example, able to follow an algorithm to solve long division. The London taxi driver on the other hand, is the pupil with relational understanding – able to navigate in a multitude of ways between different mathematical concepts.”

In the end, it must be about identifying the missing parts in this instrumental thinking and then reflecting upon how we are teaching them. As I’ve been working alongside teachers in schools, I have often heard a familiar refrain, “I have never really stepped back so much before to watch them and their learning. I am too busy ‘teaching’ the curriculum”.

Every primary teacher can surely relate to this (the ‘when do I have time’ pressure). But I can promise that every teacher I have worked with has reflected upon the impact of this investment on children’s learning without any regrets.

There are lots of ways to provide depth and breadth in opportunities so that you can reflect upon children’s learning.

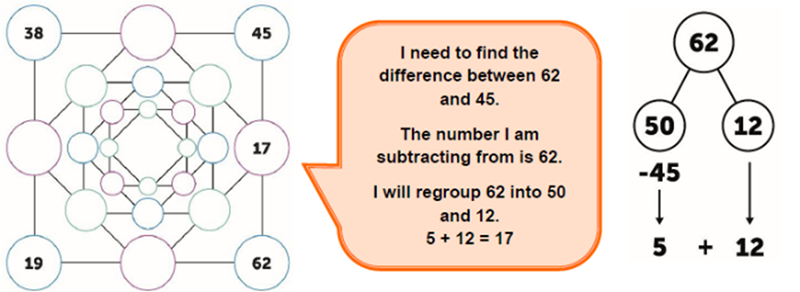

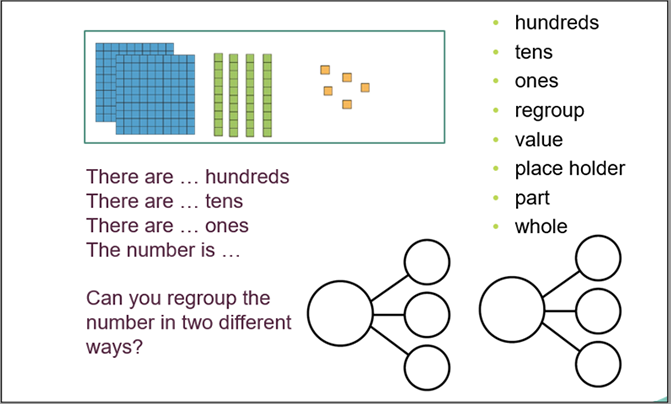

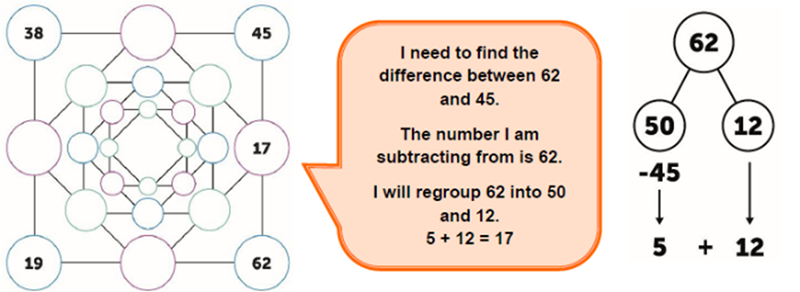

If you are a teacher in Year 3, and an ESSENTIALmaths user, you will be familiar with this game about halfway through the autumn term (3LS6). This is a really key moment (step 7) in the learning sequence.

Even if you are teaching in older year groups, have a play with this game to find any gaps in your children’s repertoire. Play the game several times and watch the strategies grow.

You can input numbers onto the outside corners to support learners or leave the children to input the first numbers and make up their own as they continue to rehearse.

Then pupils continue to find the difference between corner numbers until they either reach zero on all sides or run out of squares.

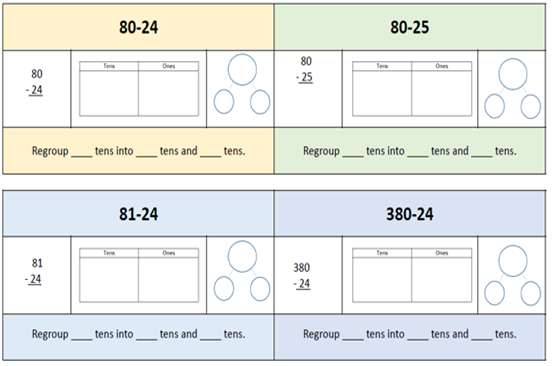

You might decide you need to go back to what they do and don’t know.

Source: HFL Education Fluency Session Materials

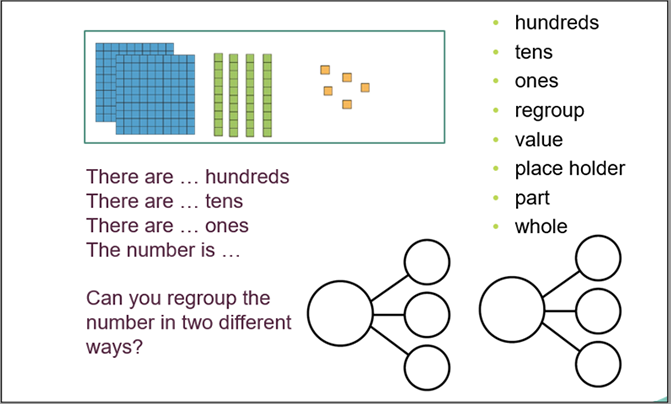

If you’re lucky enough to have taught in several different year groups, you could map the children’s learning journey from the foundation stage upwards. Sometimes the gap is much earlier in their learning.

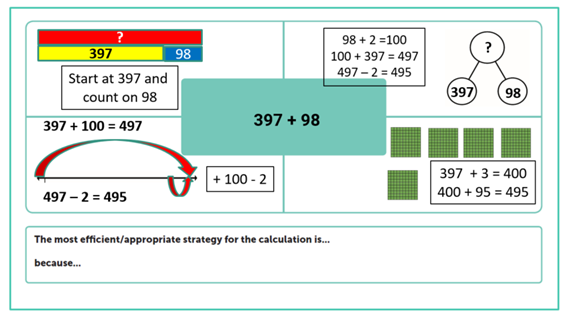

Several teachers I know are beginning to make much more use of their working walls and their fluency sessions, following similar types of analyses, to address the specific gaps they have found.

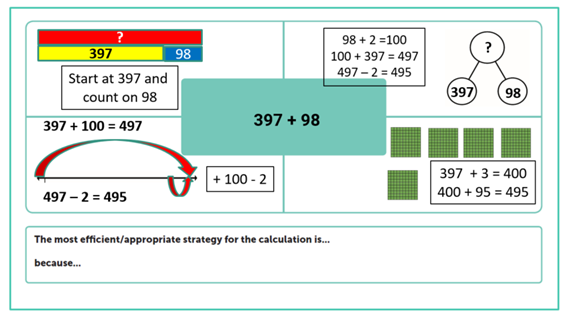

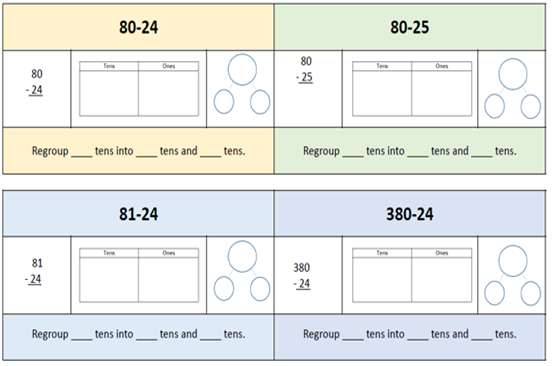

The time they have spent just stepping back and listening to children in these open activities has been fully repaid by the progress they have seen through the year. These have become ideal opportunities for regular reinforcement and continued rehearsal. Blank laminated models of ‘Multi-Strategy Mats’ and key models that are flexible for different choices of approach are helpful pupil scaffolds.

For more ideas about using working walls, read Nicola Adams’s blog 4 ways to make your maths working wall work and this one from Siobhan King: Primary maths planning, modelling and working walls – dig out your sticky notes!

Calculations to encourage and support fluency

Babbar and Ineson compared the approaches to long division of primary and secondary student teachers. They were asked to solve the problem ‘207 ÷ 23’ themselves and then outline how they would support a pupil encountering difficulty in solving it.

“Secondary student teachers were found to be more secure in the approaches that they used themselves but struggled to think of alternative ways to support pupils in developing approaches for long division. Their favoured approach was that of an algorithm...

Primary student teachers, on the other hand, could suggest a range of alternative approaches for supporting learners.”

This is the professional skill embedded in our DNA and we can’t afford to lose it.

If you fancy a little play yourself, have a quick look at these three calculations on the NCETM website and consider how you would like to teach them.

These were the examples used by Gwen Ineson and Sunita Babbar in Mental maths: just about what we do in our heads?

NCETM: Three calculations to encourage and support fluency

Is this a key focus in your school?

The HFL Education Primary Maths team can work with you in school to develop the teaching and learning of multiplication facts through The Fluency Package.

Find out more about the HFL Education Curriculum Impact Packages.

To keep up to date: Join our Primary Subject Leaders’ mailing list

To subscribe to our blogs: Get our blogs straight to your inbox

References

Nancy C. Jordan, David Kaplan, Chaitanya Ramineni and Maria N. Locuniak: Development of number combination skill in the early school years: when do fingers help? Developmental Science 11:5 (2008), pp 662–668 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00715.x

Babbar, S. and Ineson, G. (2013) Mental Maths: Just About What We Do In Our Heads? eBook ISBN9780203762585

Skemp, R. R. (1978) ‘Relational understanding and instrumental understanding’ Mathematic Teaching, 77, 20–26

Babbar, S. and Ineson, G. (2013) ‘Mental mathematics: a comparison between primary and secondary trainee teachers’ strategies’, paper presented at British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics. Bristol University, UK. March 2013.

Denvir, H. and Askew, M. (2001) ‘Pupils’ participation in the classroom examined in relation to “interactive whole class teaching”’, Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics (BSRLM), 21, 1, 25-30.

Gray, E. M. and Tall, D. O. (1994) ‘Duality, ambiguity and flexibility: a proceptual view of simple arithmetic’, Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 25, 2, 115-141.