This blog is the third in a series looking at how children make progress within foundation subjects. Here, I will aim to exemplify how children might get better at geography, with a focus on the strand of ‘physical processes,’ which runs throughout the geography curriculum we teach.

A common conversation we have with subject leaders is: How do we ensure that year on year, our children are getting better at geography rather than moving through our units of work gaining an increasing number of unrelated facts? What links the units of work? What does progress look like?

In the Ofsted subject report, published in September 2023 - Getting our bearings: geography subject report, the first recommendation is:

Consider how pupils will build on knowledge, not only within a topic but over a series of topics, so that they can apply what they have learned in different scenarios.

Seeing the whole subject, and how knowledge builds, rather than individual topics or units, is helpful when we are thinking about how a child makes progress in their learning.

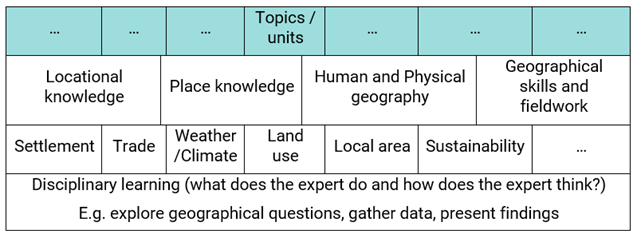

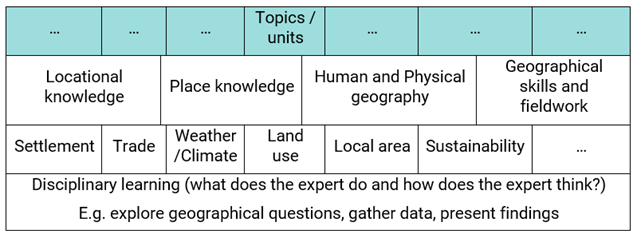

If we look at the diagram below, representing the whole of the geography curriculum, with all the learning that might be hidden under a topic or unit title, we can start to unpick the learning that takes place in geography, and it is here, I believe, we can begin to answer the question of progress.

Layers of learning in Geography

In the diagram, we can see the top layer of learning refers to the projects, topics or units of work. These are commonly found on a school’s long-term plan and are an overview of what the children will study in different year groups. Here, we may see topics such as, ‘Kenya,’ ‘rivers,’ ‘farming in the UK,’ ‘How is life in Mumbai different from life here?’ or ‘What is it like to live in the Amazon?’

The next layer refers to what we will call the concepts of geography: locational knowledge, place knowledge, human and physical geography and geographical skills and fieldwork are all identified in the national curriculum as components to be studied and are the pillars of geography. They are what make geography, geography. We cannot teach or learn geography without these central concepts.

The third layer, we will call threads. These are both concrete and abstract ideas that run through the curriculum. They appear in units of work, some repeating more than others and all of them help to break the larger concepts into smaller chunks.

Returning to the concepts layer, let’s take a deeper look at physical processes. The geography national curriculum has a heading of ‘Human and physical geography’ at Key Stages 1 and 2, which then goes onto to specify the learning that falls within this area. In an aim to make the teaching manageable, we might then create units, topics or projects, which take an aspect of the learning and explore it. But these aspects need to be still seen as part of a bigger whole, to see how learning progresses.

How might children make progress within the area of physical processes?

Physical processes are natural processes that change Earth’s physical features including forces that build up or wear down the Earth’s surface. They give rise to the spatial variation on our planet, meaning the changes that occur in specific areas or locations over space and time. Think continental drift, formations of mountains, ice caps melting or formations of rivers and how they change the landscape over time.

These spatial variations (changes in area over time) in climate, physical geography, natural resources etc have directly influenced human settlement patterns. Civilisations have flourished in fertile valleys, near rivers, lakes, shores, and coastal areas and near other highly productive ecosystems. It is physical processes that give rise to the formation of these areas and so directly affect where we live and how we live. I think this is a really important area of our geography curriculum but also a complex area to teach in enough depth for children to develop a strong schema.

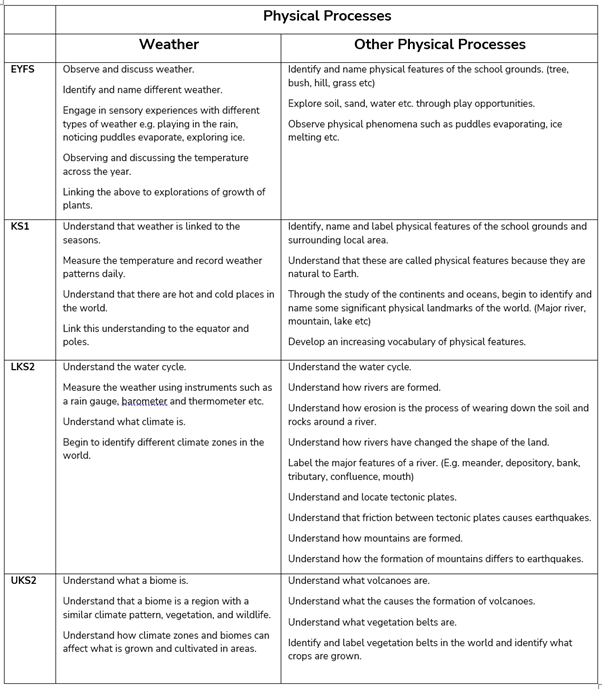

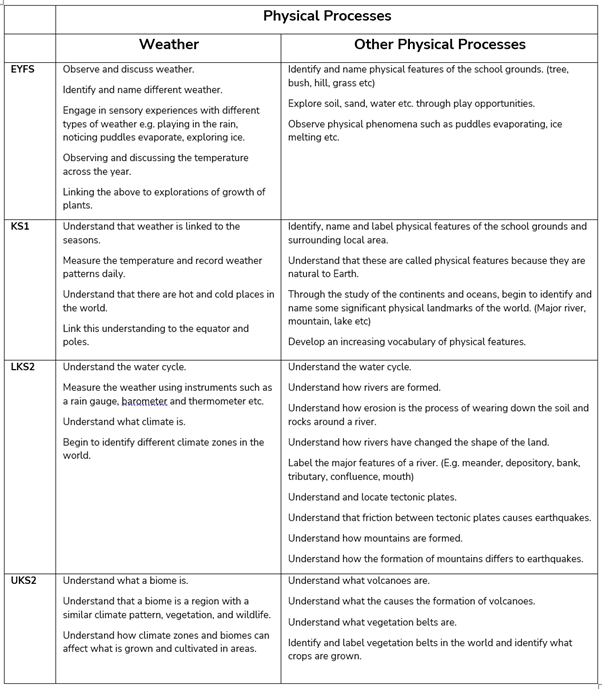

The table below is an example of what a progression within learning about physical processes could look like. As children move through the curriculum, we can plan for them to encounter this through many real life, place-related examples and so bring their locational and place knowledge to the exploration. They become more proficient and adept at understanding physical processes.

Understanding what this might look like in different age phases could help us sequence our curriculum effectively and therefore pitch our lessons appropriately; it could then underpin our assessment too.

Of course, this is one example, not an exhaustive list of possible objectives, and your geography curriculum may have sequenced the content differently.

Some learning here is sequential in its nature and needs to form the foundation of a child’s experience with physical processes. Some learning, further in the curriculum journey, is about strengthening and securing a child’s schema around physical processes by meeting the learning in many contexts. This is achieved by providing many contextualised examples, thus widening the child’s understanding, and creating a strong schema.

What might this look like in the classroom?

In EYFS, the learning is experiential and provides the foundation for all future learning. A child may be busy observing and discussing weather with an adult. They may notice that puddles form when it rains. They will discuss what clothes to wear on a hot day or a cold day. A child may engage in play with soil, sand and water noticing some of the properties of these materials and engaging in a simple discussion with an adult. They will begin to point out and name physical features of the school grounds and build their repertoire of vocabulary. This will also be developed through play, stories, video clips etc. of other places. These types of experiences are essential and a foundation to future learning about the weather and other physical processes.

During KS1, a child may engage in a daily class activity recording the weather. They will learn that the weather relates to the seasons. They will also begin to make links between the seasons and growing plants. They will build on the work in EYFS and extend their vocabulary by identifying a greater range of physical features through studying the local area and other places.

Also in KS1, a child may build on the prior learning above by identifying hot and cold places in the world and relating these to the position of the equator and the poles. They will expand their vocabulary further when identifying physical features especially when studying a place very different to their own in their non-European study. Here, children may encounter physical features that are not in their own locality and begin to identify some significant physical features in the world (deserts, mountains, coasts, rainforests, jungles, etc)

This learning, within Early Years and KS1, provides the basis for future learning. As children move through the curriculum step by step, all future physical processes knowledge will be built on these foundations.

As children move into lower KS2, they progress from identifying and labelling physical features to exploring physical processes. The learning from KS1 provides a bedrock foundation for new learning to sit and stick. Without these first steps, children will struggle to understand other content. For example, early experiences with seasons relating to plant growth and knowing there are hot and cold places on the planet provide the basis of a schema in which knowledge about vegetation belts and climate zones will later sit.

A child in lower KS2 may study the water cycle. They might relate this to the formation of rivers. They will understand that the formation of rivers has changed the landscape. They might link this to their Year 3 science topic of rocks. They may also link their learning to the local river where they may undertake investigative fieldwork identifying and labelling the river parts, making sketches and measuring water flow etc. They could also contextualise their learning by exploring, ‘what is it like to live near a river?’ in a study of the Amazon River for example.

Children in lower KS2 may also learn about mountains and how they are formed. To understand this, they will need knowledge about tectonic plates. This will rely on knowledge about the continents studied in Year 2. They will recall prior learning about significant physical features of the world and may remember some well-known mountain ranges. They will understand how mountains are formed and may investigate a region in Europe that contains mountain ranges. They may also investigate earthquakes and how the friction between tectonic plates causes them. To contextualise learning, they may study a region that has suffered from earthquakes and discuss their impact on people and land. Teachers could help children create strong schema by making the link between rivers and earthquakes as two physical processes that change the Earth’s features and impact the way we live.

Children in upper KS2 may investigate how volcanoes are formed; they could link this learning to prior learning about tectonic plates. They will draw on their expanding location knowledge to use more complex maps to locate volcanoes around the globe and begin to analyse patterns. To contextualise their learning, children may investigate the question of, ‘why do people choose to live near volcanoes?’ Here they may link their learning to case studies of one or more places. For example, farming in the Naples region of Italy can sometimes be difficult due to the limestone basement rock. However, due to the lava-rich soil, they are able to grow vines, vegetables, flowers etc. In Iceland, geothermal energy is used to heat swimming pools and buildings. These case studies are two examples of how human and physical geography are interconnected; they bring classroom learning to life and take the learning about physical processes from an isolated knowledge bank into a more real life, rounded view of the processes being studied and their impact on humans.

As children move towards the end of the planned curriculum in upper KS2, they will be able to weave together much of their substantive knowledge and make links between different areas of learning. They may investigate different vegetation belts and explore case studies, by, for example, returning to look at the Amazon River as a South American place study, recalling knowledge of rivers and moving to looking at what crops can be grown and how the land is used. This links physical and human geography. They may look at case studies of coffee farmers and explore cash crops and fair trade. Children may also return to look at their local area in more depth undertaking fieldwork linking together all four concepts of geography.

In the examples above, we can see that the knowledge secured in EYFS and KS1 provides a foundation for future learning; a place for new learning to connect to and stick. The learning provides the foundations necessary for what comes next.

When children reach KS2, the learning about physical processes broadens and deepens. Here, it might be less important what order some of the learning is presented in and more important to focus on schema development – connecting learning by presenting the knowledge of physical processes in a range of contexts, linking to real places studied and combining with the other concepts of geography. Here the teacher needs to narrate the learning; drawing children’s attention to where ideas have been met before, and how things connect.

With this approach to building a strong schema, the key is to highlight, and relate all learning to prior learning. This is how children make sense of their learning and begin to connect the different knowledge bases of geography. This is making progress. The stronger the schema, the better the recall and the deeper the understanding.

The stronger the schema, the better the recall and the deeper the understanding.

This blog by Tom Sherrington is useful for thinking about schema if you want to delve further.

The important point here is that we can view the way children make progress within the thread of physical geography in more than one way:-

- In a more sequential, linear manner; with each year and topic they study, they become more proficient as their skills build incrementally.

- In a manner more like mastery where children develop a rich schema around the thread by meeting it many times in many different contexts throughout the curriculum.

In summary, if we want these teaching moments to be meaningful, we need to draw the children’s attention to the learning where they have met it before. Highlighting the prior learning and where they will meet the ideas again in subsequent topics, ensures that a constant thread is pulled through the geography curriculum enabling children to progress.

In answering the question, how do children get better at geography? here are three factors that leaders may wish to think about:-

- Children can get better and make progress within the concepts that underpin geography hierarchically, if these are planned for in an incremental way, as shown in the example progress table.

- They can develop a rich schema around these concepts, to master the ideas, by purposefully meeting knowledge in many contexts, weaving the four concepts of geography together, with the adult drawing their attention to the concepts as they are revisited.

- The points above might work best when we purposefully plan the opportunities and highlight them to the children. ‘Do you remember when you looked at tectonic plates and how their movement may cause earthquakes? Well today, we are going to look at how tectonic plates play a part in the formation of mountains…’, which might require a combination of both points 1 and 2.

In your school;

- Is there an understanding of the geographical concepts that underpin learning in geography (location knowledge, place knowledge, human and physical geography and geographical skills and fieldwork)?

- Do adults purposefully draw pupils’ attention to these concepts and where they have been met before (to allow pupils to develop schema)?

- Do adults understand how this learning might grow and develop over time as pupils mature (thinking about the progression table idea)?

In subsequent blogs, we will exemplify further concepts in other foundation subjects asking the key question, what does it mean to make progress?