This blog is the second in a three-part series. It follows on from Part 1 which was published on the 26th of May 2023.

My conclusion in Part 1 contained the statement: ‘There are often words and phrases in education linked to the disadvantage gap such as ‘reducing’, ‘closing’, ‘diminishing’ or ‘removing’ it. Perhaps, in the 21st Century and beyond, the ‘gap’ will remain as societal, and other conditions mean that it exists and can be out of our full control. Our mission remains though. To enable all children to access and engage in rich learning and feel a deep sense of belonging in it. This will be explored further in Part 2 with the implications of not acting accordingly analysed in Part 3.’

In this blog (Part 2), I will focus on what that looks like in practice and in Part 3 I will explore the implications of what happens with young adults when their needs are not met early in their education.

Introduction

To enable all children to access and engage in rich learning experiences requires careful consideration. Both the building and establishment of this scenario require specific forethought to ensure effectiveness. In a HFL Education Services meeting at the beginning of this academic year, our Chief Executive Officer, Carole Bennett, and Co-Directors of Education Services, Jeremy Loukes and Liz Shapland initially reflected on the sporting successes across the country during the summer, including ‘The Lionesses’. These were celebrated as positive outcomes in challenging times and allowed me to reflect on all of the groundwork, planning, commitment and constant evaluation and adaption that is required to achieve those outcomes.

In his book, ‘Habits That Make A Champion’, Allistair McCaw asserts that,

‘Becoming a Champion or High Performer doesn't happen overnight or by accident. It takes years of dedication, hard work and discipline. You can have all the talent in the world, but if you haven’t developed the right habits and mindset, you will always fall short of your greatest potential.’

The rationale behind this is beautifully summed up with the statement:

It is this rationale that formed the basis of my exploration into how schools are addressing the issue concerning the aforementioned societal gap, and thus providing a sense of belonging for all of the children in their charge.

Championing the cause in a primary school

At Commonswood Primary and Nursery School in Hertfordshire, meeting the needs of children who are presently disadvantaged is the main ‘driver’ in the School Development Plan and is always the priority when any decisions across the school are made.

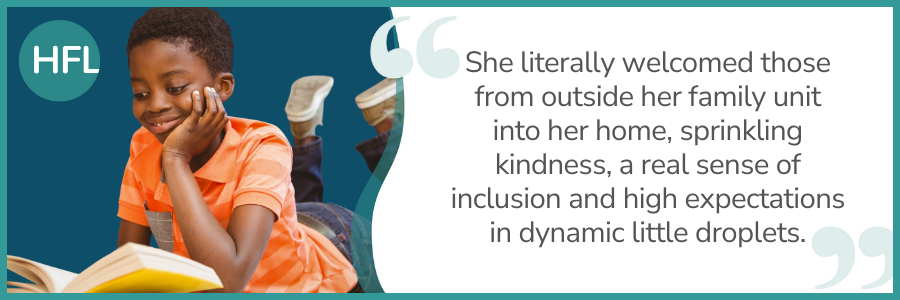

With demonstrable passion and clear allied commitment, the headteacher, Gill Seymour, shared the school’s integrated processes and the strategies employed:

- preparing for transition at the end of each academic year by identifying and analysing potential barriers together with parents and carers to support personal needs. This ‘Nurture for all’ approach is underpinned by the key question, ‘What does this look like for our school and what is our clear strategic intent moving forward?’

- focus on inclusion in after school clubs. 94% of all children and 96% of children presently experiencing disadvantage attend clubs. This includes all children from one family attending at the same time if taking part is dependent on this being facilitated.

- initial home visits for children who join the school after Reception or part way through an academic year. These allow teachers to get to know the family and their needs in a familiar environment and contact is made on a weekly basis to support the children with settling in.

- access to the ‘Helping Hands Home Care’ service to provide specific support to families.

- personalised tracking of children presently experiencing disadvantage who also have SEND. This process is supported by the governors.

- tracking absences daily. Teachers phone parents/carers as necessary to offer support and children who have been absent are welcomed back on their return.

- employing a Speech and Language specialist with an ‘expert eye’ who works beyond the school day to be available for families at a time convenient to them.

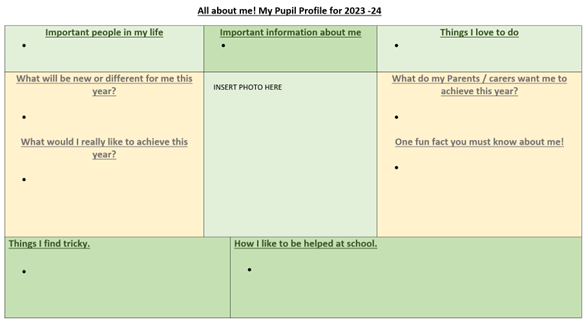

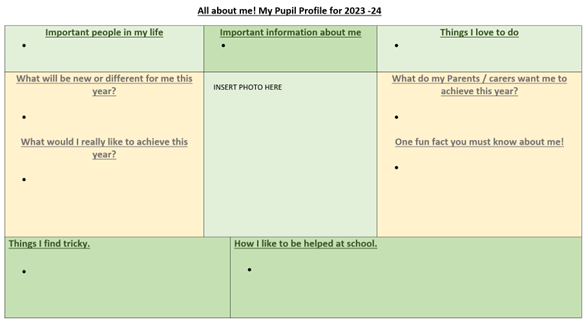

Pupil profiles

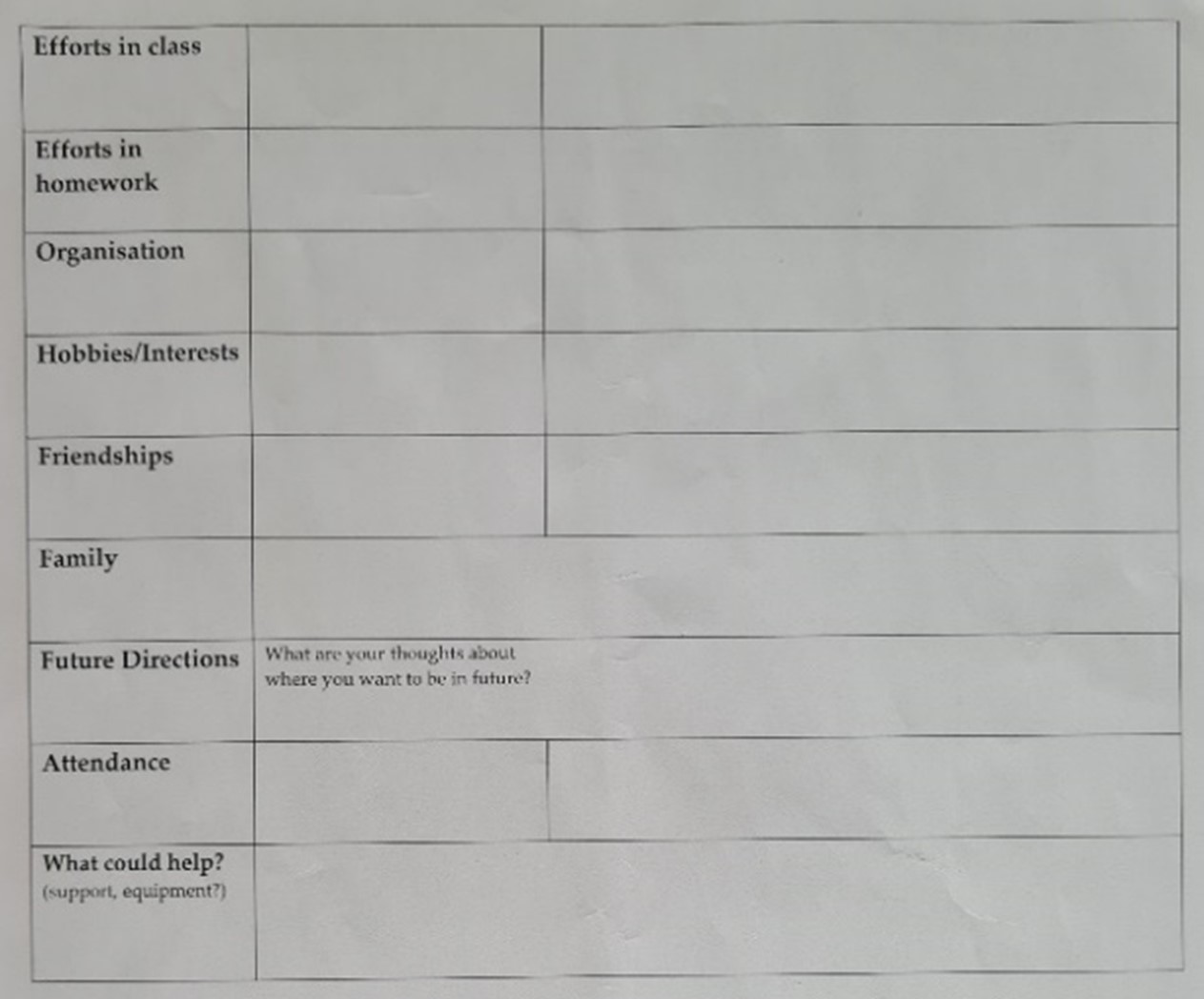

Along with an appropriate adult, the children contribute to a personalised ‘Pupil Profile’.

An example:

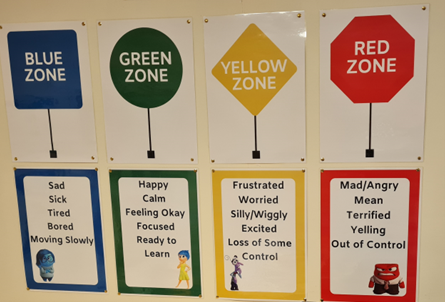

Alongside the pupil profile, a personalised ‘Emotion Regulation Plan’ is created with specific ongoing review dates.

This will include potential triggers for escalation of negative emotions or behaviours and measures that should always in place.

- Measures may include:

- processes for information sharing during the school day to support transitions

- check-ins by designated adults

- additional classroom support tools

- designated safe space to go to if frustrated

Pupil premium strategy

Finally, the ‘Statement of Intent’ in the school’s Pupil Premium Strategy Plan outlines the key rationale for the introduction of these processes:

‘A whole school ethos of attainment for all. The Commonswood motto ‘Aim high’

reflects our high expectations for the whole school community and we are an ambitious

school in every respect. We are determined to create a climate that does not limit a

child’s potential in any way. We have a strong personal commitment to improving

outcomes for vulnerable pupils’ attainment. We have high aspirations and ambitions for

all our children, and we believe that no child should be left behind. It is essential that all

disadvantaged children, including young carers and those who have, or have ever had

a social worker, make at least good progress from their starting points and that no gap

between them and non-disadvantaged children remains.’

Statements made by Gill demonstrate the impact of consistently delivering the overarching aims across the school and include:-

- teachers know the children well

- all children in the school are treated uniquely

- it only takes one person to make a difference in helping disadvantaged children

- we need to display a ‘different way’ that encompasses the needs of all children

- all of the children in school recognise the value of education

- homework club is for all children and sets them up to succeed

- we need to go beyond the child to achieve success

- our disadvantaged children without SEND outperformed the non-disadvantaged children last year

In the school’s latest Ofsted inspection (January 2023), the Personal Development of the children was judged to be outstanding.

Championing the cause in a secondary school

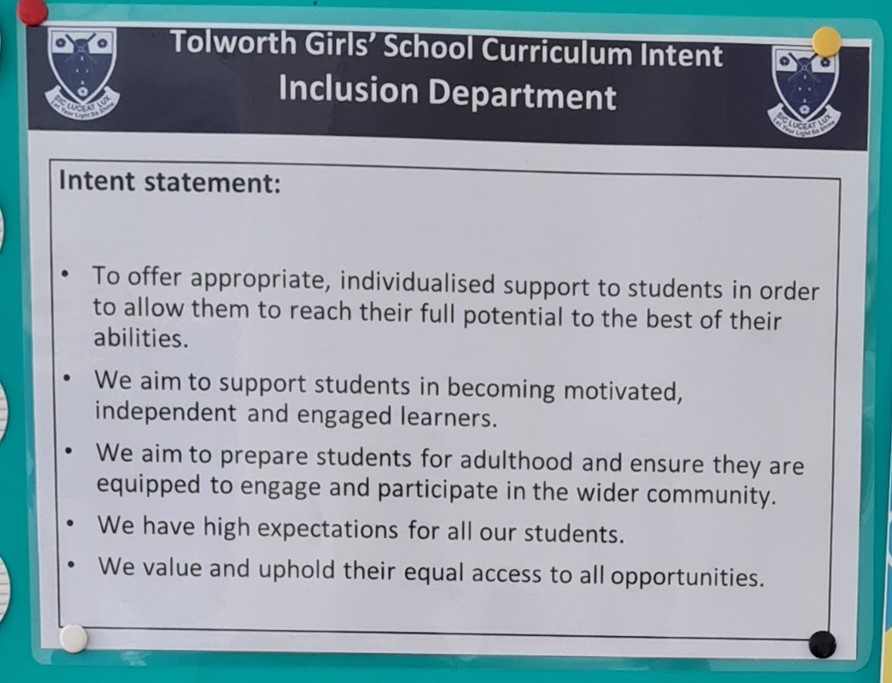

Meeting with the headteacher, Jolande Botha-Smith, and the Inclusion Team at Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form in Surrey, provided me with an overview and analysis of the ‘habits and behaviours’ that lead to positive results.

Meeting with the headteacher, Jolande Botha-Smith, and the Inclusion Team at Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form in Surrey, provided me with an overview and analysis of the ‘habits and behaviours’ that lead to positive results.

The academy’s SENDCO, Robyn Munro, shared the history and structure of the team and explained how it has expanded dramatically over time from being housed in a small ‘shed’ to its current purpose-built facility. This was driven by the increasing necessity to address escalating numbers of students who had personalised needs.

The current team includes an assistant SENDCO, a team of specialist Teaching Assistants, Student Support Workers, a Transition Team, an EAL coordinator, staff who can speak / interpret a wide variety of languages and a Careers Team. Collaboration enables the facilitation of an in-depth approach to meet the needs of the students.

Charlotte Clements, the Student Welfare and Child Protection Lead, shared these approaches:

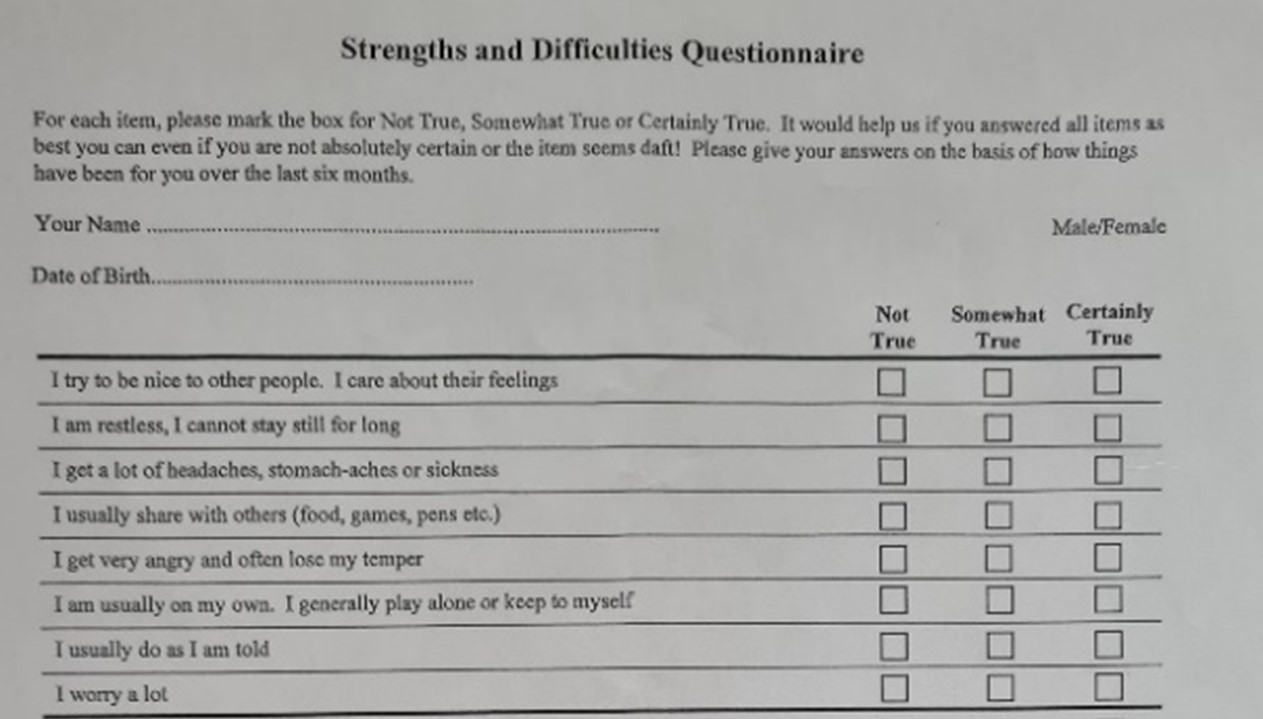

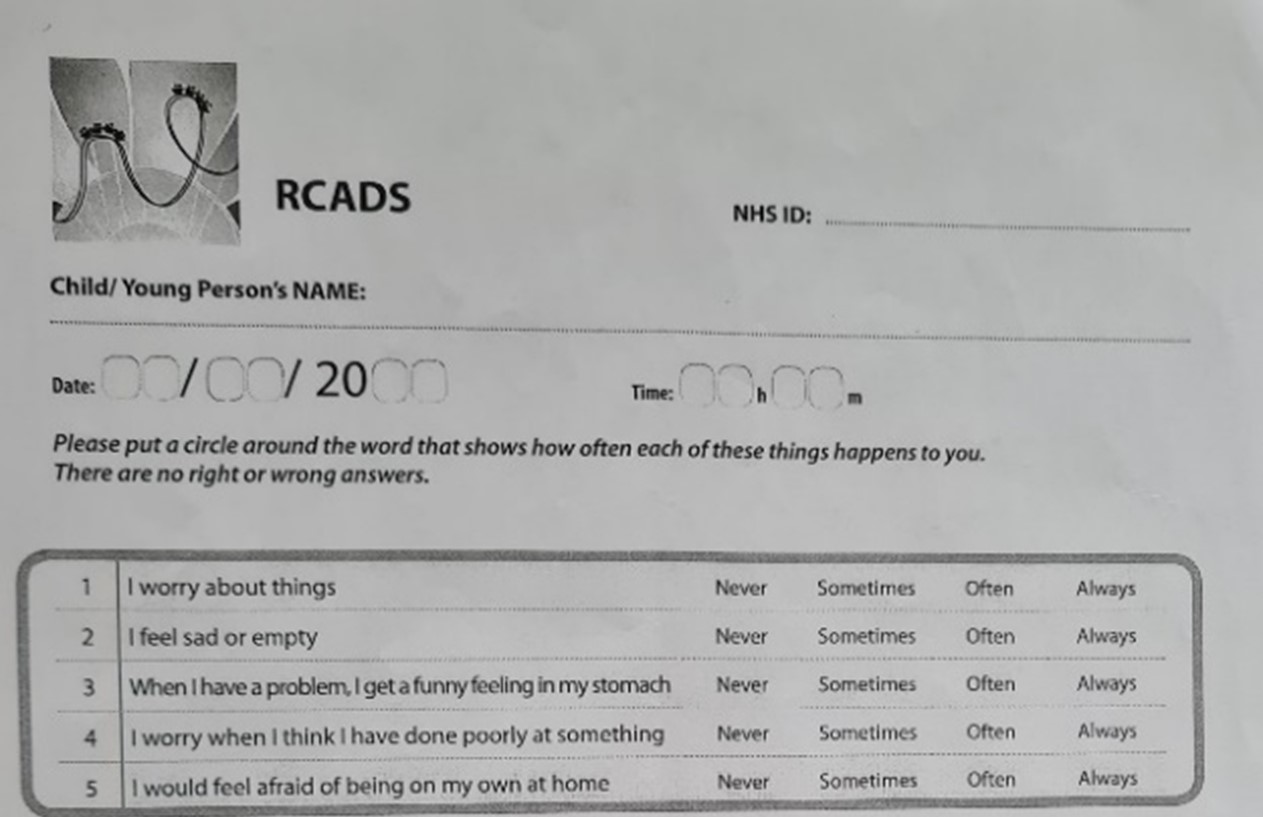

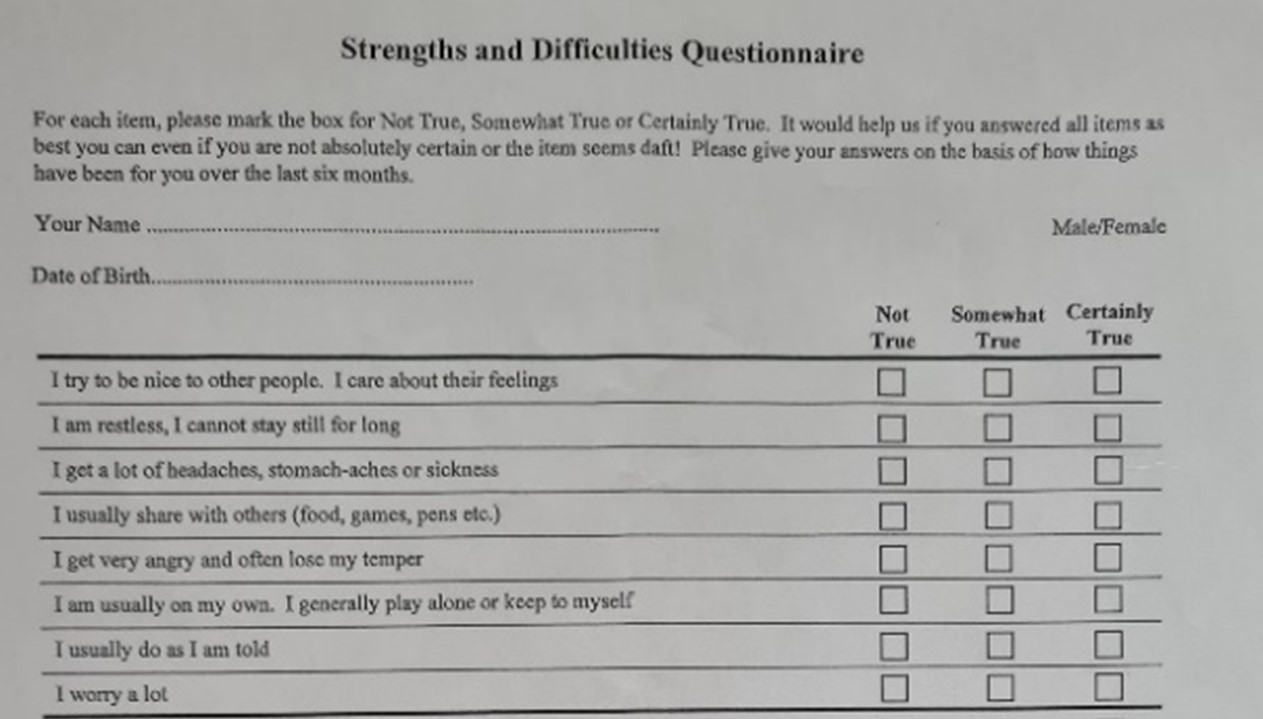

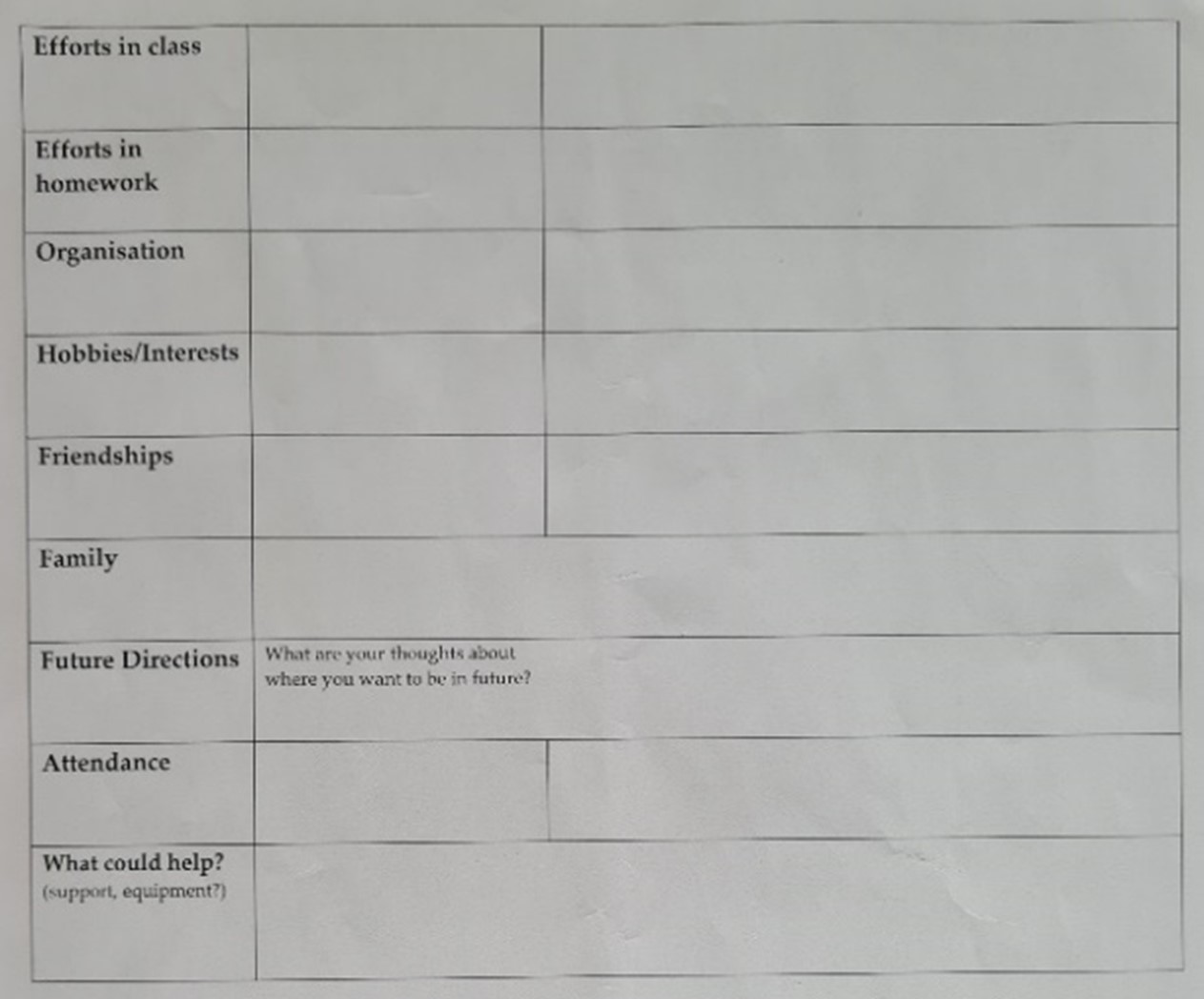

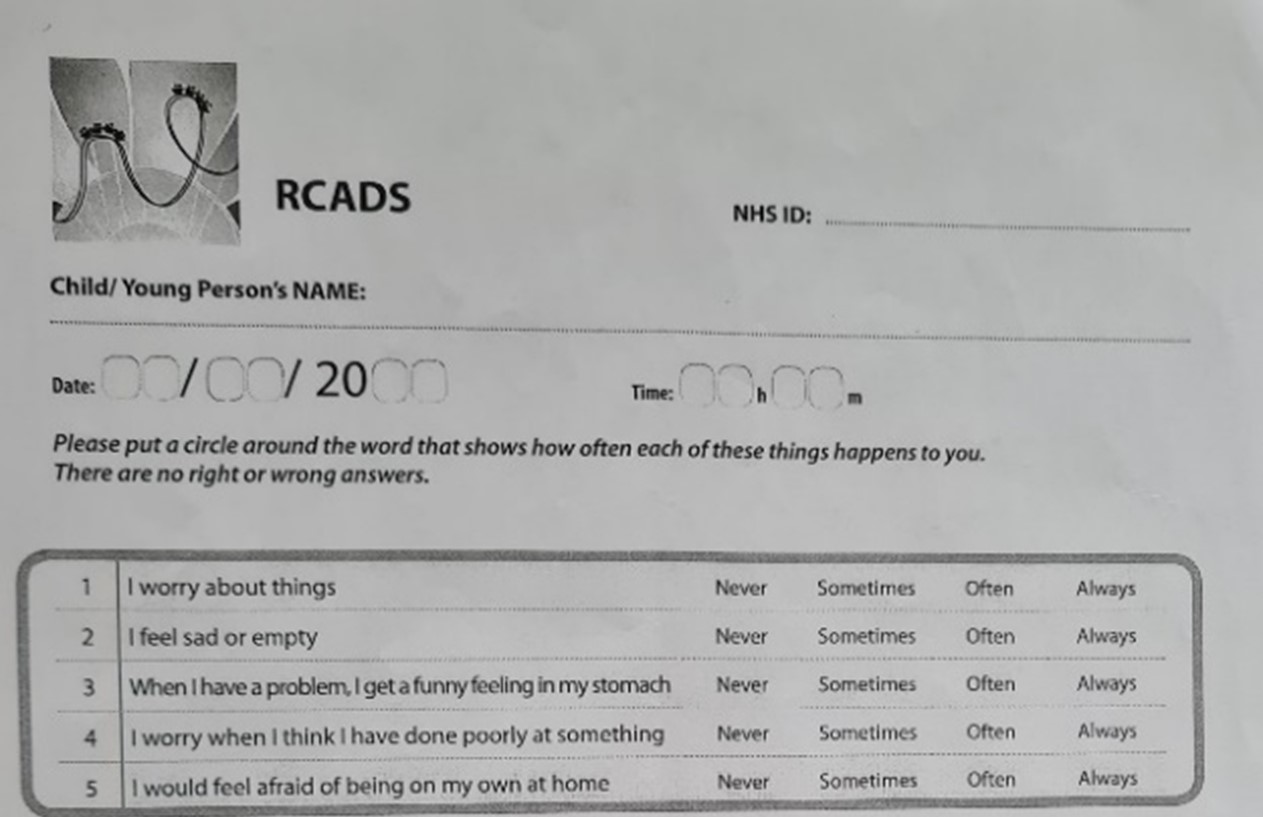

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire and child self-report

(examples from sets of wide ranging questions)

The data from these reports can also be analysed to highlight any specific area of concern that may be prevalent. For example:

- social phobia

- panic disorder

- major depression

- separation anxiety

- generalised anxiety

The SENDCO uses pupil responses to ‘unpick’ the underlying causes of behaviours and then implements strategies to address them. This may require further support from outside agencies. Robyn also wholeheartedly agreed that a key factor in this process is addressing the ever-changing ‘societal gap’ that clearly exists in current times.

The academy’s initial focus is on ‘getting to know the students inside out’ to allow them to access the curriculum with a ‘sense of belonging’, rather than a ‘top down’ approach linked to academic attainment.

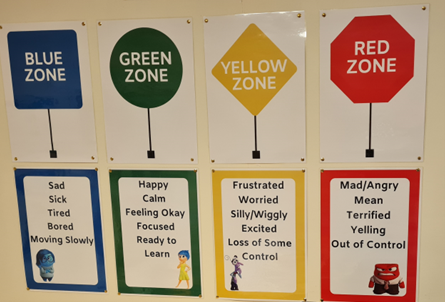

This process is augmented through continuous ‘in person’ involvement with students where the Student Welfare and Child Protection Lead is always available, predominantly outside lesson time, for consultation as required. This supports students who feel that they cannot express their concerns ‘in the moment’ so they refer to a specific ‘zone’ that is displayed: this is then further analysed and next steps considered to allow access back to the ‘Green Zone’:

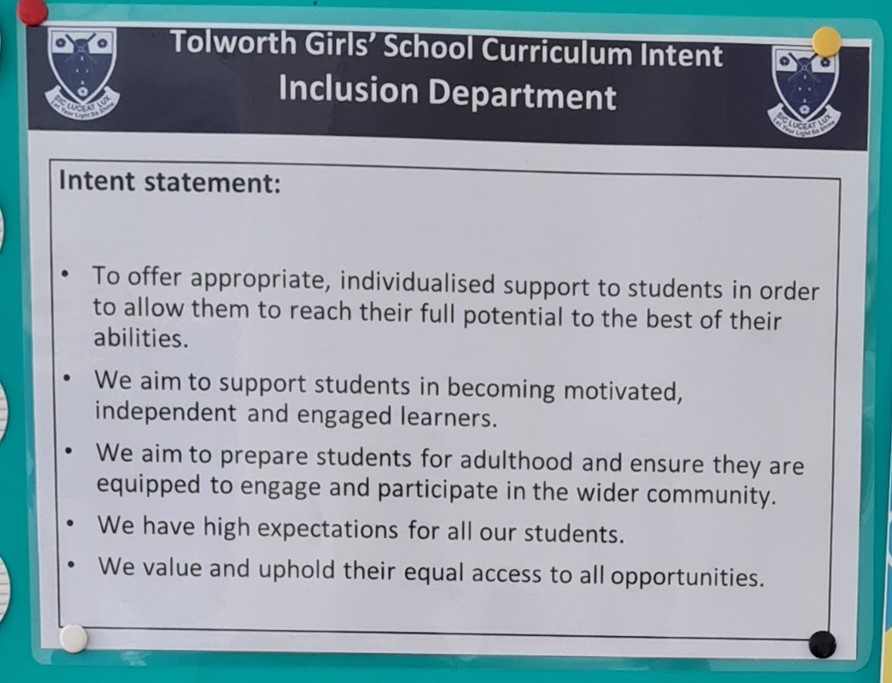

Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form has approximately 1,457 students who mature quickly as they progress through the academy. This results in their personalised needs, especially their well-being and sense of belonging, can present as being more complex. Jolande spoke passionately about the aims of her school and how they are preparing the students for life in the adult world. The ‘brief overview’ of the PSHE curriculum in Year 11 states: ‘Our aim is to allow the students to discuss issues within the wider world. From living on their own to forced and arranged marriages. As a school we believe that Year 11 is the time to have more mature and open discussions with students’. She also stated that early identification of children's needs is paramount. This is initiated through a specific transition programme where the ‘new to Year 7’ students spend one day as the only Year Group in the school to get used to the surroundings. They are then paired up with an older student as a peer and confidant. The Inclusion Team use the documents that have been displayed here to facilitate personalised and individual understanding of every child. This is driven by the rationale across the academy for the prioritisation of inclusion, without exception, and is reflected in Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form’s Curriculum Intent statement:

The headteacher clearly ‘lives and breathes’ this rationale and demonstrates an unerring commitment to achieve success for all through the significant enhancement of the Inclusion Team which is robustly monitored for impact on a daily basis. A ‘deep dive’ was carried out recently by a visiting headteacher who described Inclusion and Safeguarding in the school as outstanding.

‘Championship’ (as in ‘the vigorous support or defence of a person or cause’)

In both schools, the needs of the learners are met through precise actions that produce ongoing consistent outcomes.

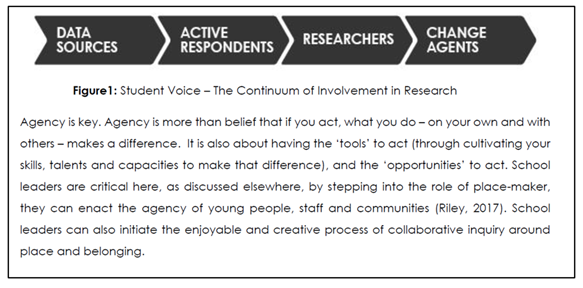

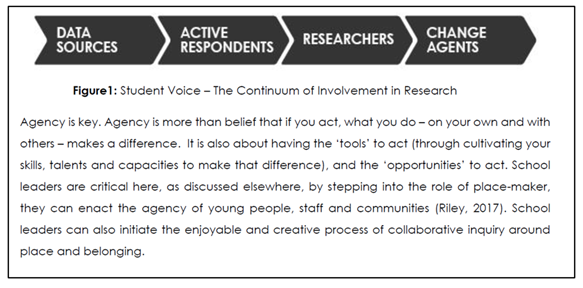

In the Journal of Educational & Child Psychology, Kathryn Riley (2019) relates this process to ‘AGENCY AND BELONGING’ and asks the question ‘What transformative actions can schools take to help create a sense of place and belonging?’

One consideration is through the relationship of the processes to ‘The Continuum of Involvement in Research’:

The school leaders I have referenced in this blog have undoubtedly stepped into the roles of ‘place-makers’. They have formulated teams that have analysed data (which is initially predominantly qualitative), involved the children/students as active respondents in research through the identification of issues about their own learning. This has contributed to leaders’ knowledge and understanding about the required changes and subsequent improvement.

This has been instigated as early as possible whenever children/students join the schools. Under the heading ‘Creating a sense of belonging for your students’ Allen K.A et al (2018) analyse this further with the generalisation that, ‘More broadly, Maslow (1968) found that proper, adequate and timely satisfaction of the need for belonging leads to physical, emotional, behavioural and mental well-being’.

Effective use of time was also a key factor in the ‘Lionesses’ recent success. In September 2021, Sarina Wiegman became England Women’s head coach. Within a year, she had made history guiding the Lionesses to become EURO 2022 champions. In 2023, they narrowly lost in the Women’s World Cup final. To have significant impact in a short time frame is impressive, and the journey to achieve that started by developing the right learning environment for the squad. In England Football Learning (2023) Wiegman asserts ‘That’s where it all starts, with creating an environment in which there’s trust, and it’s safe.’ The key to that approach is communication. Ultimately, to develop trust, connections need to be built.

‘Start with talking with each other and asking questions on and off the pitch. Just asking questions and telling a little bit about yourself. Then you learn about players. Every player – every human being – is different, so it’s good to learn about each other. Then you can also adapt your approach to the player to get more out of her.’

This environment of trust is clearly evident in both the school and the academy where all of the children feel safe and secure knowing that their multifarious needs will be addressed in cyclical processes. The situation has been achieved against a backdrop where Riley (2019) declares that

‘Belonging is that sense of being somewhere where you can be confident that you will fit in and feel safe in your identity, a feeling of being at home in a place and of being valued (Flewitt et al, 2017; Riley, 2017). In a world in which social and economic divisions are widening and more people are displaced – exiled and homeless - than at any time since the end of the 1939-45 War (Putnam, 2015: UNHCR, 2017), schools need to be places of belonging.’

To further illuminate the situation, Dan Nicholls (2023), in his latest blog entitled ‘Towards Social Justice’, reveals a stark reminder and a clear alert of the outcomes if the situation is not addressed with haste:

‘Our education system is perfectly designed to secure and maintain the conditions that accumulate disadvantage over time. A system so ingrained and accepted that we unwittingly perpetuate it and see the results as inevitable. Against the backdrop of the fracturing social contract, the aftermath of the pandemic and in darkening times, the cogs of the system continue unabated, galvanised and renewed to further widen gaps and disenfranchise an ever-larger number of children.

The system is strengthening, forging greater division in society precisely at a time when individual agency and mobility is decreasing. A system that has powerful ways of telling children that they do not belong, playing out asymmetrically to make life precarious and insecure for far too many. A national crisis rages, children are becoming more invisible, opting out of education and they are being pushed to the edges. Those who most need school are not there, absent and missing from the very place that could offer social justice and opportunity.’

The term ‘social justice’ is intimately linked to the ‘societal gap’ as the thread running through both Part 1 and Part 2 of this blog. Dan Nicholls (2023) makes this connection clear by stating:

‘Seeking social justice and how our system increases participation, connection, opportunity and experience is better placed than initiatives focused on mobility, which seek to enable relatively few individuals to escape the system, to defy the odds. We need a bottom-up investment in all individuals; we need to change the rules of the game with social justice as the goal and social mobility as an outcome’

For me, this is undoubtedly achievable if the attributes of ‘championship’, as described, become universally accepted and employed, along with the associated actions and strategies. The ‘end goals’ are attainable. We need to grasp the opportunity before the situation spirals completely out of control.

We are the champions

In the utilisation of the word ‘We’ in the title of this conclusion, I am, of course, referring to the potential that anyone holds when they are in a position to influence the lives of young people. This extends far beyond life in school but a major proportion of the time that most children move from infancy to adolescence is spent attending educational establishments. During that time the primary focus of all the personnel involved in that process must be to champion the aforementioned cause.

Carole Bennett recently shared a ‘TED Talk’ entitled ‘How to create a high-performance culture’. In it, Andrew Sillitoe relates to rethinking how we can create an environment where everybody can thrive, feel inspired and operate at their full potential with a sense of purpose. He suggests that we are losing our purpose in society and if purpose is about meaning in our lives, it is about staying engaged when things become challenging and, from a leadership perspective, it is about connection with the audience. If that connection is attempted with a focus purely on the leader and not the intended impact and ‘what that actually looks like in action and the participant’s role within it’ then the connection is completely lost.

Clear connectivity is profuse within the establishments referred to in this blog. They have an inherent understanding that a constantly shifting societal gap exists and are positive about overcoming its challenges through a flexible and adaptable personalised approach. Within that, roles are clearly defined, with their associated accountability, and a profound sense of purpose exists as an integral part of creating a ‘sense of belonging’ to allow access for all. This encompasses both personal development and the accompanying life skills. For me, the overarching theme that emanates from my visits is the headteachers’ absolute commitment to achieve success for all the children and young adults in their charge. It is abundantly clear that their influence, by effective leadership, has significant impact, not only within their schools but also in the wider context of the ‘outside world’. This has been achieved through the implementation of systems and processes, that are constantly evaluated and adapted in an ever-changing landscape, where the focus is ‘not on results but on the habits, subsequent mindset and associated behaviours that produce them’. The formulation of this scenario and its ongoing impact will allow all children/students to become champions themselves in ‘Minding the gap and ensuring that they take their belongings with them’.

At HfL Education we are acutely aware that there is a wealth of amazing inclusive practice going on in schools, settings and trusts across Hertfordshire and beyond. This blog has focused purely on two of those establishments, where ‘deep dives’ were carried out.

In Part 3 of this blog, I will be exploring and analysing ongoing situations, along with the associated consequences, that can occur in young adulthood and beyond, if a sense of belonging is not realised.

References

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Waters, L., & Hattie, J. (2018). What schools need to know about belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1-34. Download: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L. M., Moffitt, C. E., Umemoto L. A., & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 835-855.

England Football Learning (2023): https://learn.englandfootball.com/articles/resources/2023/Sarina-Wiegman-the-importance-of-communication

Maslow, A. H. (1968) Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand.

Nicholls, D (2023). Towards Social Justice https://dannicholls1.com/2023/10/01/towards-social-justice/?s=03

Putnam, R. D. (2015). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Riley, K (2019). Journal of Educational & Child Psychology: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10103208/1/Riley_Journal%20of%20Education%20and%20Child%20Pyschology%20%208%20July.pdf

Sillitoe, A. (2015). Ted Talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BAdeFHlhKi4

Meeting with the headteacher, Jolande Botha-Smith, and the Inclusion Team at Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form in Surrey, provided me with an overview and analysis of the ‘habits and behaviours’ that lead to positive results.

Meeting with the headteacher, Jolande Botha-Smith, and the Inclusion Team at Tolworth Girls’ School & Sixth Form in Surrey, provided me with an overview and analysis of the ‘habits and behaviours’ that lead to positive results.