Shining a light on Development Language Disorder (DLD)

Research shows 23.7% of learners identified with special educational needs, have a speech, language and communication need (SLCN)-it is the most common type of need for those receiving SEN support. (Special educational needs in England 2023 DfE). With Friday, 20 October 2023 marking Raising Awareness of Developmental Language Disorder (RADLD) around the world, and an estimated 7.6% of children having DLD, now is the perfect time to share some helpful tools and resources with you.

Landmarks around the world will glow yellow and purple to shine a light on this often hidden-but common-disability in celebration of Developmental Language Disorder Day.

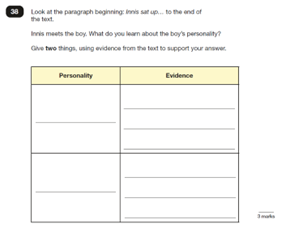

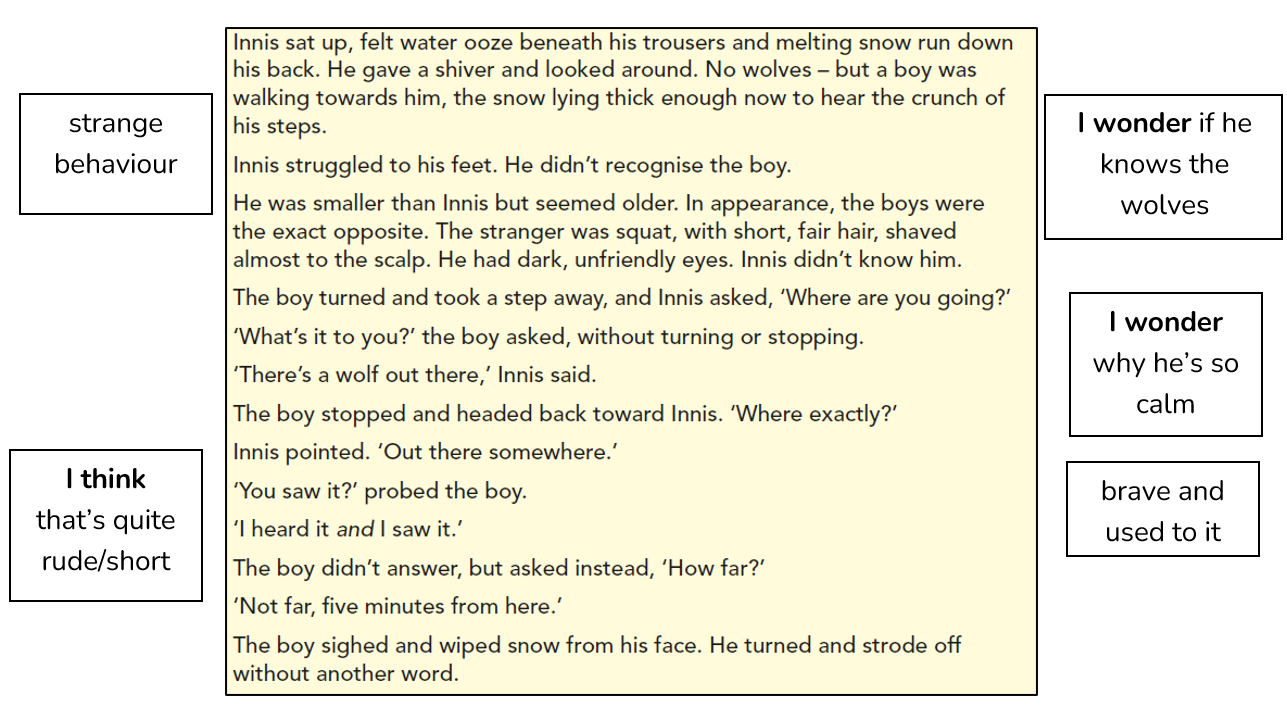

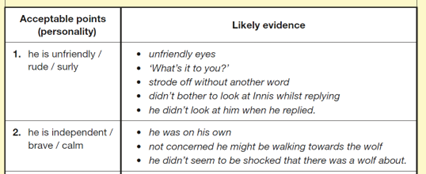

What is Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)?

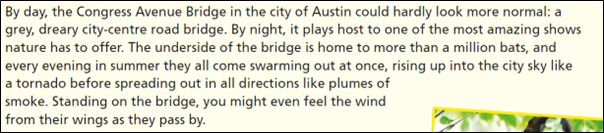

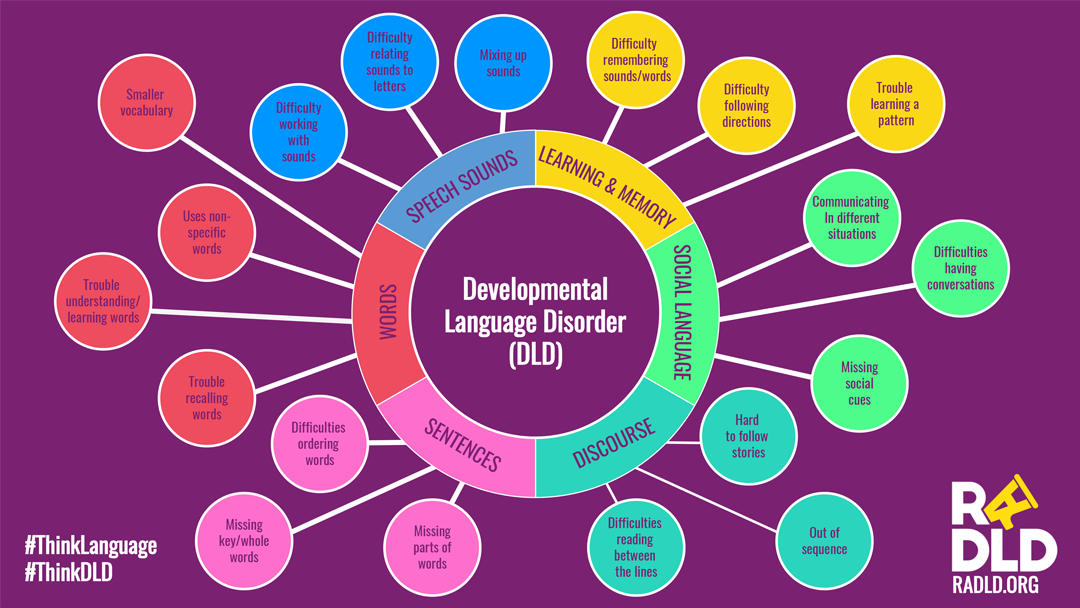

People with DLD have long term difficulties understanding and/or using spoken language creating challenges to communication and learning. There is no known cause of DLD although it can run in families. In the classroom you may notice learners who experience a range of DLD related barriers to learning. This poster provides a useful summary.

What classroom support strategies work well?

Explaining, questioning, making and sustaining friendships - these are just some of the daily language demands for learners before we even begin to consider the need to learn curriculum specific language. Ensuring high-quality teaching strategies support the development of speech and language skills for all learners will go a long way to ensure learners with DLD can succeed. Here we reflect on some ways teachers and teaching assistants can support.

i) Creating a communication supportive environment

We all have situations as teachers we never forget. For me teaching a child with DLD, in an English lesson was one of those moments.

We were examining a text and the main character ate a hot dog. The child, gasped, looked at me with wide terrified eyes and bellowed across the room, “No Miss! No!”

It took me a moment, but, looking into those panicked eyes I realised the child thought the character was at a funfair eating an overheated dog!

Context is everything in reading but when you have DLD that connection is harder to make.

Looking back, I wished I had used visual scaffolding to support the key message of the text.

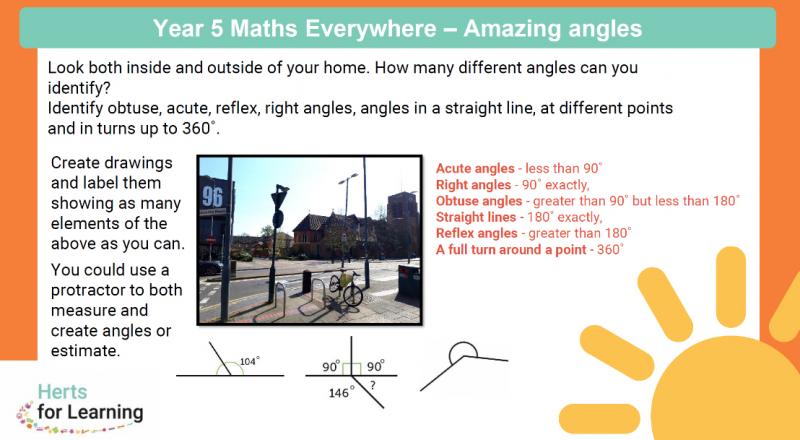

Using appropriate scaffolds can work well as a key facet of ‘adaptive teaching’. Scaffolds can often be created live or become embedded within planning rather than feeling like an ‘add-on’

Gary Aubin, EEF, 2022

This child (and the whole class for that matter) could have been signposted to the images as we read/discussed/analysed the text. For me, a quick image search on the internet resolved the misconception, but what if the child hadn’t had the confidence to shout out to me? How many of our learners are missing language hooks and therefore the entire meaning of our teaching?

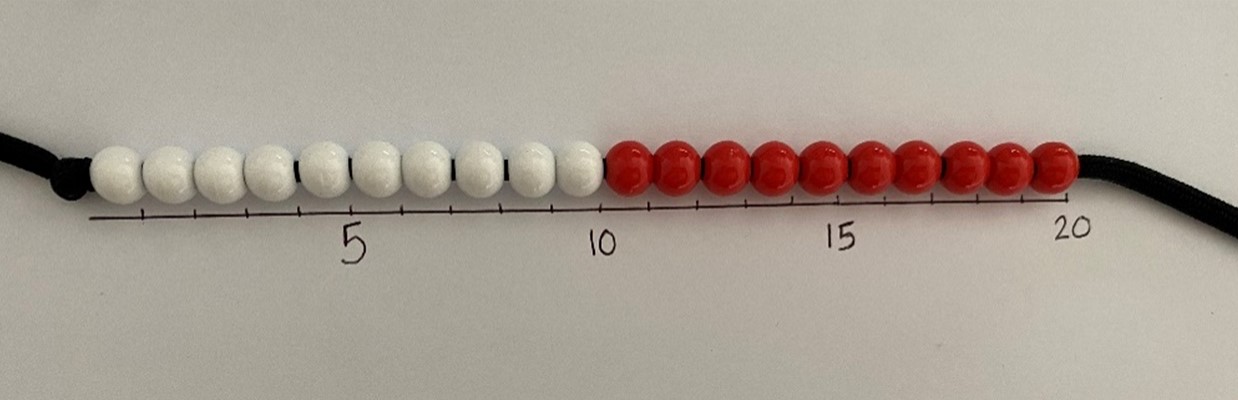

Having key vocabulary displayed with an image is often referred to as dual coding. For further information on dual coding explore the work of Oliver Caviglioli.

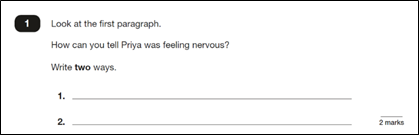

ii) Explicitly teach language

Alex Quigley highlights the benefits of helping all children to “grow their vocabulary” in his book Closing the Vocabulary Gap, 2018. When embedded into whole class teaching this approach will also benefit learners with DLD. Quigley refers to the SEEC model:

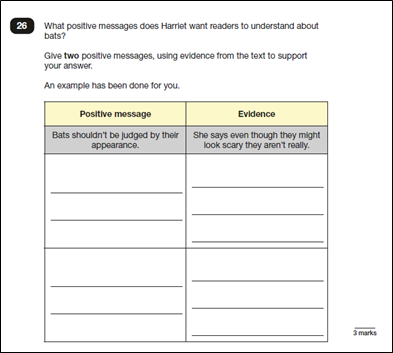

Select: reflect, in advance, on the key vocabulary that connects and supports knowledge.

Explain: discuss the word, meaning, link with phonemic awareness (regardless of age/stage) and give learners time to discuss examples.

Explore: understand the word and give learners a chance to unpick it.

Consolidate: repeated exposure of vocabulary supports embedding over time. Think where you can provide overlearning opportunities that are quick, succinct and support to embed language understanding.

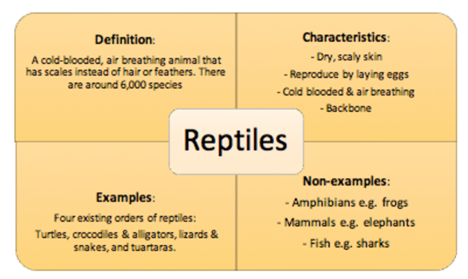

Quigley demonstrates this approach using the Frayer model.

Taken from Alex Quigley: The Confident Teacher

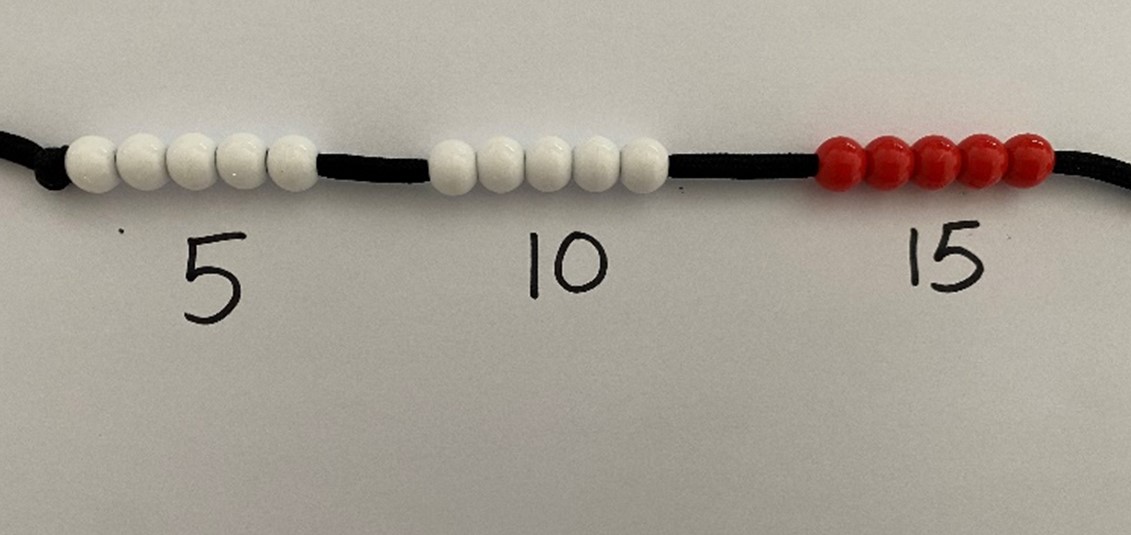

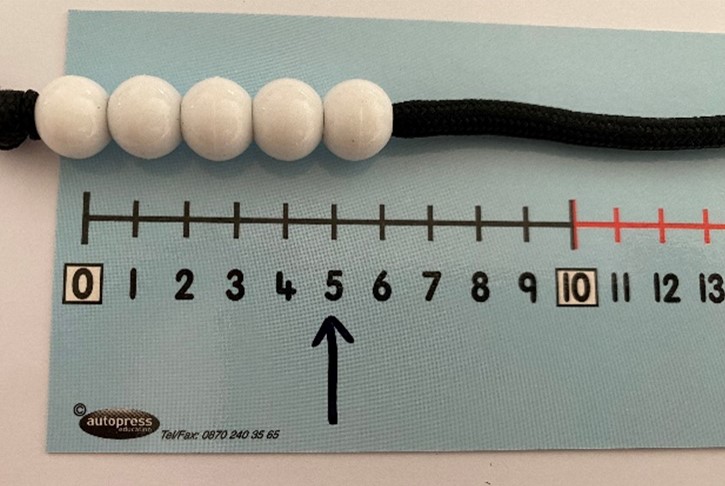

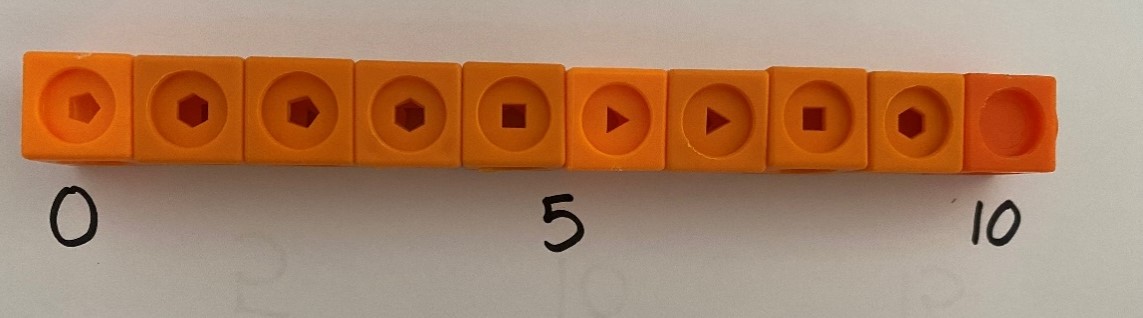

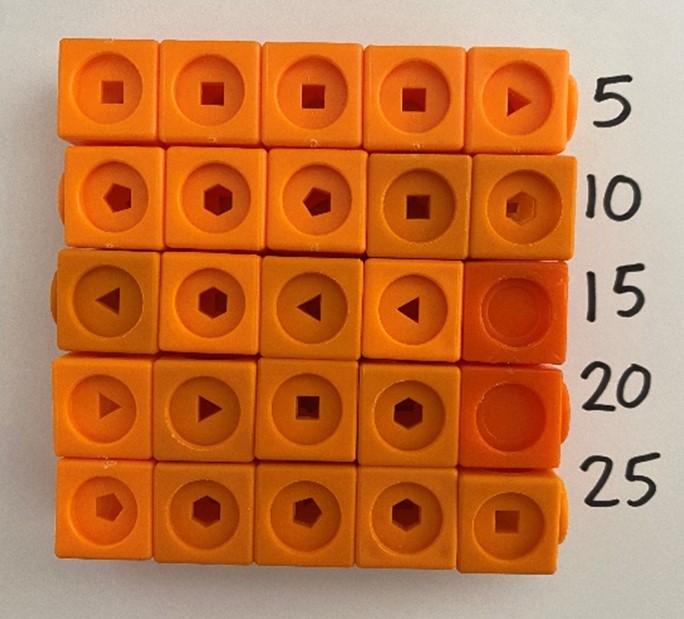

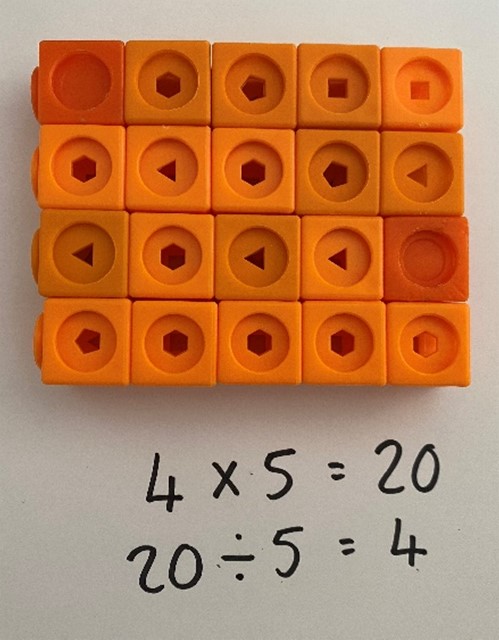

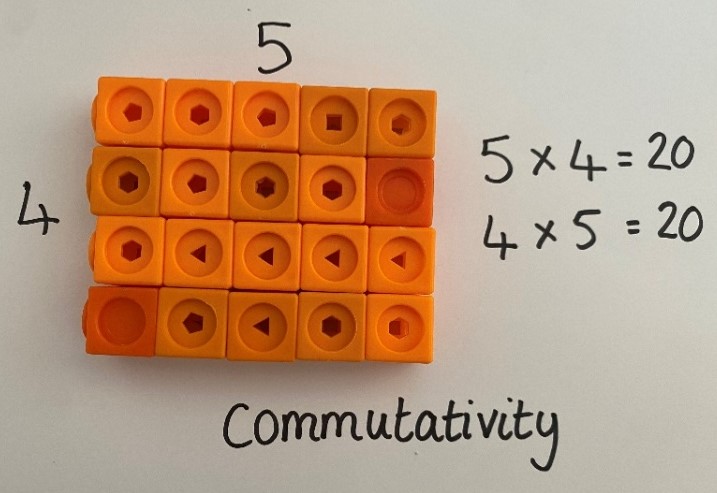

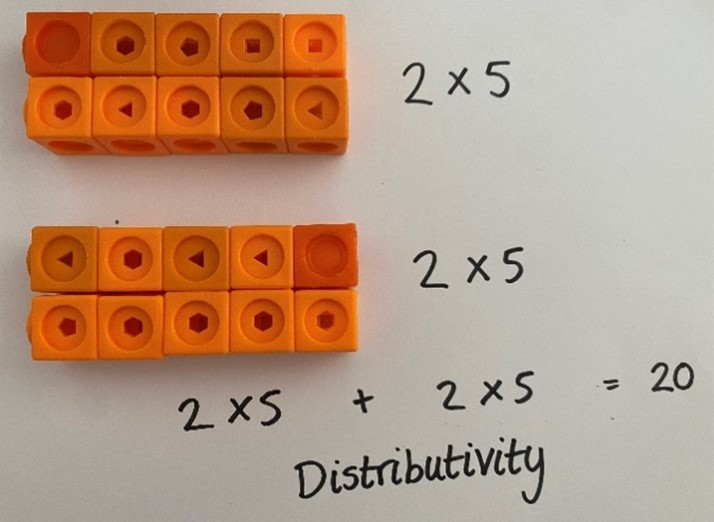

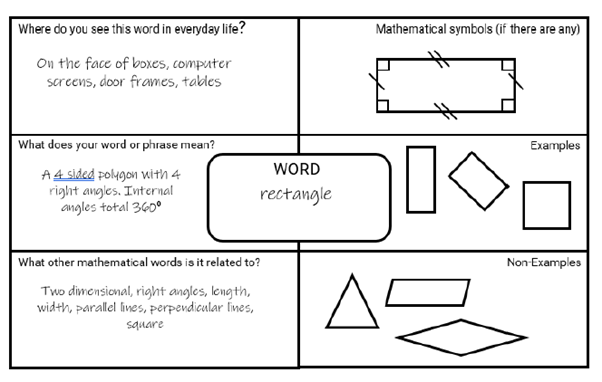

At HFL Education this approach is reflected in the mathematical vocabulary index resource. By teaching and learning mathematical language pupils will be able to clarify and organise mathematical knowledge. (HFL mathematical vocabulary index resource.)

HFL Primary Maths

By making explicit visual connections with language all learners, including those with DLD, will be exposed to a considered, language rich model. For those of you who are senior leaders, you may wish to consider how you could embed this across all phases and curriculum areas.

Developmental Language Disorder is the most common communication need by far… Around 85% of those children are probably not identified, and so teacher awareness is a really big area for support.

Stephen Parsons SEND Huh (2023)

In support of DLD Day, here is a small selection of my favourite resources to raise teacher awareness:

- Hertfordshire’s SEND Toolkit provides direct links to training and resources from the Children and Young People’s Therapy Service including an excellent quick reference guide. Consider displaying the poster in the staffroom or sharing with families as the QR codes takes you straight to a wide range of organisations.

- Speech and Language UK have a wealth of practical resources and guides for all ages including a support guide for teachers on DLD. Consider using the communication friendly checklists to audit the provision in your school for learners with DLD.

- ICAN’s DLD guide for teachers in mainstream schools has plenty of practical advice on supporting families, class-based strategies and identification processes.

Finally, do have a look at the RADLD website to not only promote DLD Day in your own school but also to support staff to gain a better understanding of the condition.

Remember HFL Education’s SEND advisers can provide CPD on visual scaffolding. For further information email hfl.SEND@hfleducation.org

So, when you see that yellow or purple glow-on social media, in the news or in the sky- please do take a moment to reflect on the challenges that so many of your learners face each day and-more importantly-consider the small change you put in place to support learners with DLD.

In the spirit of raising the profile of DLD, as we celebrate DLD Day, please consider sharing this blog with colleagues. #DLDday