Year 6 teachers and pupils will now have transitioned into the new academic year, and we know it won’t be long before plans steer towards preparing for this year’s SATs. No doubt many will be thinking back to the controversy surrounding the 2023 Reading SATs papers and (despite the Standards and Testing Agency reporting that the content was “set to an appropriate level of difficulty”), we recognise the challenges it provided for many.

In this blog, we hope to provide an easy-to-follow analysis of the reading SATs papers, but more importantly, further insight into teaching practices of reading, to develop classroom pedagogy further.

60 minutes, 3 texts and how many words?

This year, pupils were expected to read and analyse the following texts:

- “A Noise in the Night” from Survival Squad: Night Riders.

- “Bats Under the Bridge” from a New York Times article.

- “A Howl at Dusk” from The Rise of Wolves by Kerr Thompson.

You can find the full reading booklet for the test here.

The test required pupils to read a total of 2106 words across three texts. This is almost a third more than the 2022 paper, which included only 1,564 words. On average, pupils would only have had around 34 seconds to read and answer each question. This, however, should not tempt us to teach to the test and most certainly not under time constraints. Guided reading in a pressure cooker is only going to create undue stress and anxiety for our pupils. We know we need to create diverse opportunities within quality teaching to allow our pupils to comprehend the meaning of what they read, using a wide range of engaging texts.

Connecting content domains

The updated Reading Framework (2023) has provided some insight into the teaching of reading comprehension strategies. It advises that schools should not be limiting their learning objectives solely to the ‘content domains’ (appendix 10). It discusses the importance of drawing on and using a variety of these strategies, all of the time:

- activating and using background knowledge

- generating and asking questions

- making predictions

- visualising

- monitoring comprehension

- summarising

We will elaborate on this later using example questions.

First, let’s break the vocabulary barrier

The HFL Education conceptual model shown here and the EEF’s Guidance, discusses the importance of explicit, quality teaching of reading with an awareness of vocabulary knowledge as a barrier. The 2023 paper was jam-packed with vocabulary that required background knowledge and varied lived experiences. It is often the foundation of any reading test and with word meaning questions (2d) on the rise from 10% in 2022 to 18% this year, it’s certainly an aspect to focus on. In paper 1 alone, children encountered words such as rustling, throbbing, grid, emerged, binoculars, rustlers.

So how do we prepare children for this task?

You’ve guessed it…explicitly teach vocabulary.

Which words should we be teaching and when?

Tier 2 words: challenging, ambitious words with characteristics of written language. Teach words that will potentially disrupt the overall comprehension of a text. See here for more. Be sure to familiarise them with unknown words prior to reading to help lessen comprehension difficulties. However, when reading as a class or group, it would be best to do this when the word is encountered in the text.

Life beyond definitions!

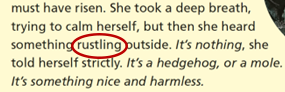

Research shows that introducing a new word using its dictionary definition can be problematic. Let’s look at the word ‘rustling’ as an example:

Dictionary definition:

- the sound that paper or leaves make when they move.

- the crime of stealing farm animals

By depending on these definitions, children would need to first work out which definition links to the context of the text: is it a noise or stealing? They would then need to figure out which one is making the sound. Is it paper or leaves? For most children, this process will have already started to overwhelm them. It is more effective to provide children with the meaning of the word using every day, familiar language and also explore the essence of a word and how it is used. More strategies are shared in ‘Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction’ by Beck, McKeown & Kucan.

Here are some more word attack strategies you could begin to model within your reading lessons:

See Reading SATs strategies for the final stretch for more word attack strategies!

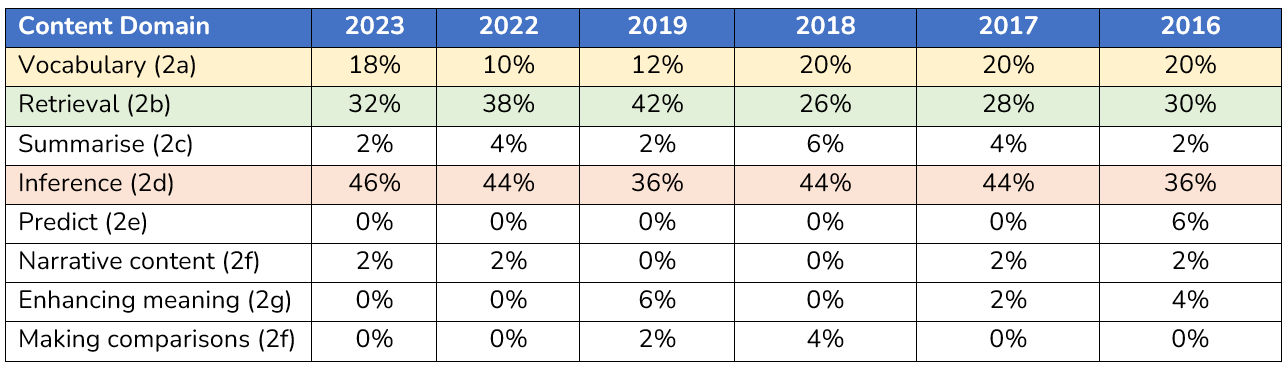

We can see how, since 2016, the SATs questions have also focused heavily on testing retrieval and inference:

Inference investigation!

It’s worth asking:

Do pupils know what ‘good readers’ do as they read?

Do they know that when we read, we are visualising, making connections/comparisons and drawing on our own experiences?

Do they know that words hold meaning, often deep enough for investigation?

Do they know that inference often includes looking for clues and evidence, and that there can often be more than one answer?

Do they know that we often need to depend on background knowledge, extra information or clues?

Let’s take a closer look….

In the first text, ‘A Noise in the Night’, pupils are provided with this information:

There will be children who have never experienced camping, and certainly not on a farm. This strengthens the importance of ensuring that the texts we read (and re-read!) transport children to many different places – ones they may not have experienced in real life.

In previous tests, question 1 is usually a simple retrieval question, but here we have a 2-mark, inference question from the get-go.

To infer successfully and receive the full two marks, children will need to:

- re-read the text

- connect with Priya and recognise the symptoms of/examples of nervousness

- draw on their own experiences of feeling nervous in similar situations

- only retrieve from the first paragraph

- retrieve two different pieces of evidence from the text

The more you know; the more you learn

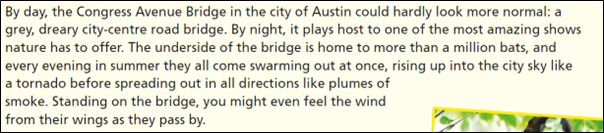

Let’s dive into this non-fiction text:

Off the bat (pun intended!), children will hopefully have some background knowledge. Background knowledge supports comprehension, but it can be particularly critical when reading non-fiction texts. In this instance, pupils will hopefully work out that ‘Congress Avenue Bridge’ is a place in the USA. Later, they will also need to grapple with words: capital, city and state.

Most of the questions in this section assess pupils’ ability to retrieve and record information. Easy, right? Perhaps not with this level of challenge: long, multi-clause sentences, figurative language and complex words and phrases.

Again, teaching children to break up the text into meaningful chunks and showing them how to read words in context will aid their ability to do so with ease and at a sufficient speed.

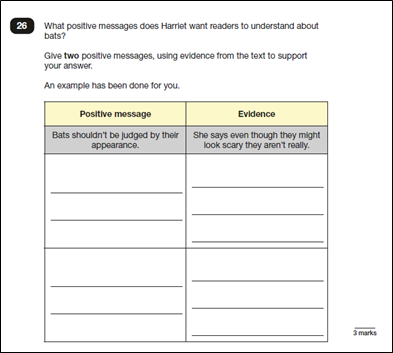

Positively prepared… or maybe not?

Many Year 6 teachers will have prepared their students by setting questions using recurring question stems from past papers. E.g. “How can you tell that…” “What does this tell you about their character?”

The unfamiliar wording of this question would certainly have caused some frowned brows…

Children often hear the word ‘positive’ being used in many different contexts: “be positive/use a positive mindset” or, very possibly in a scientific context, too. The challenging job here is that children need to:

- understand that bats are usually viewed in a negative light (either from background knowledge or from the text itself)

- find two different messages that are deemed to be ‘positive’ in this context

- scan large amounts of text quickly

To answer questions like this successfully, pupils need to have experienced regular, well-planned, rich reading lessons, that allow them time to see and practise:

- reading and re-reading passages again and again (…and again)

- reading at length

- returning to the text

- exploring/discussing vocabulary purposefully and actively

- taking part in rich, in-depth discussions with their peers and teachers

We must find time to guide pupils to connect with texts with this level of difficulty. Only then will they feel equipped to tackle them with resilience.

The End is Near…

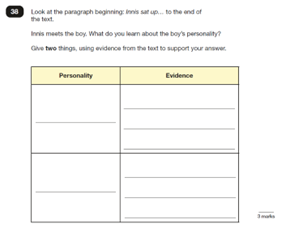

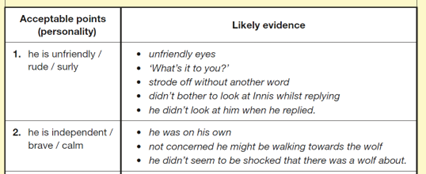

It’s no surprise that the final question is worth 3-marks. But wait! “What does personality mean again?” A question that no doubt echoed across the classrooms of those children who made it to the end of the paper in time.

In this blog, we discuss strategies to support children to answer 3-mark questions, such as, ‘what’s your impression of…’. For many experienced Year 6 teachers, this very question is emblazoned across working walls and referred to constantly. However, to our surprise, this higher-level question was also phrased differently.

The National Curriculum states that children should “identify and discuss themes and conventions in and across a wide range of writing”. Although this question is asking for a character study, we can teach children to hunt for themes and conventions to support them to do this. Support children to dissect the text. Are there themes of love, courage, hatred, friendship, magic that they notice?

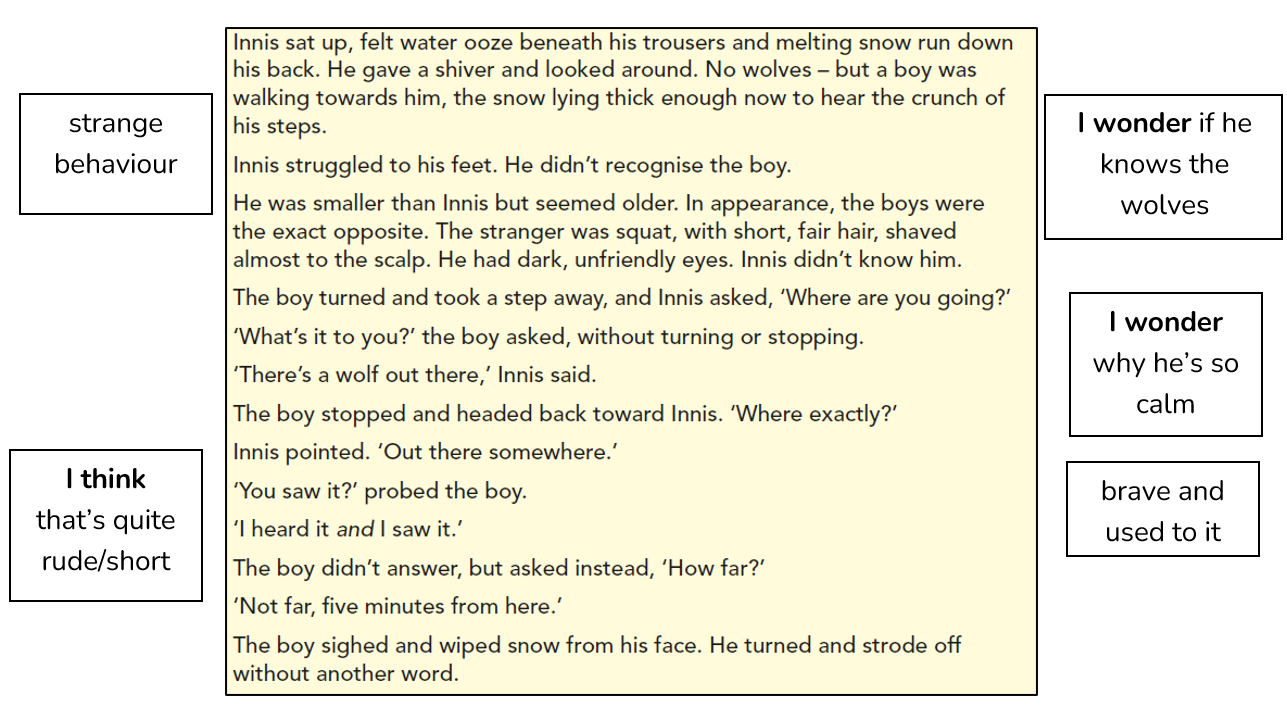

Read aloud and think aloud!

When we model reading aloud, we should model thinking aloud, too. This allows children to develop active thinking whilst reading. Embedding sentence stems such as “I wonder…”, “I see…” and “I think…” helps children to think deeply about these themes and conventions in relation to character behaviour/personality.

In his book ‘Reading Reconsidered’, Doug Lemov talks about the importance of Interactive Reading. He says we should teach children how to interact with the text by “underlining, marking up key points and summarising ideas in the margin.” Elaborated thoughts can transform into brief text interactions during timed tests and other reading tasks.

Eventually, pupils will be able to organise their ideas efficiently and analyse character behaviour with ease. Practise in groups and pairs until pupils develop the confidence to tackle independently and accurately:

Are all of your pupils fully engaged?

As mentioned in the reading framework, ‘PISA data consistently shows that engagement in reading is strongly correlated with reading performance.’ With that said, here’s a few suggestions that you might want to consider:

- Start by carving out some precious time within the teaching day for children to explore and engage with texts in depth

- Find a way for each and every pupil to engage and interact deeply

- Build a community of readers, who not only read within your classroom, but outside too

- Take time to closely monitor children’s reading habits so that you can recommend books and share your personal favourites

- Facilitate opportunities for book talk and most of all, provide plenty of time to actually read

We hope that this blog provides a starting point to get you thinking about the ways in which you might interpret the findings of this year’s reading SATs paper outcomes and how these findings might be translated into effective guided reading practice.

Most importantly, let us remember that the SATs are a short moment in time. The rich reading experiences we provide children can set them up for life. Let’s give them tools they will take with them wherever they go: a love of reading; a love of books.

Blog originally published: 23/11/2023.