Reading fluency has been enjoying something of a renaissance in recent years; after an extended period of arguable neglect in England, there seems to be a great and growing deal of interest. As well as being a hot topic, it’s sometimes something of a hot potato. In the evidence base related to reading fluency, this aspect of reading has sometimes been described as ‘controversial’ or ‘a can of worms’. In part, this is because of the ways by which fluency has been variously defined. In part, it is because of the ways by which approaches to developing fluency have been implemented. And partly it is because of differing views in terms of its overall importance.

Some notable books on reading do not explicitly tackle the concept of fluency as a single entity and as an aspect of reading proficiency. This includes Seidenberg’s Reading at the Speed of Sight, and Dehaene’s Reading in the Brain, though both go into great detail in relation to aspects of fluency, and the cognitive processes that underpin those aspects, such as those that lead to automatic word reading (code learning, orthographic mapping). Elsewhere, references to reading fluency have been incomplete or unduly fragmented. A notable example would be the 2018/19 KS1 Teacher Assessment Framework (TAF) for reading which included the following bullet point:

In age-appropriate1 books, the pupil can:

• read most words accurately without overt sounding and blending, and sufficiently fluently to allow them to focus on their understanding rather than on decoding individual words

In the most commonly accepted, contemporary definitions of ‘reading fluency’, accuracy is an integral part of fluent reading, so the apparent separation of ‘accurately’ from ‘fluently’ could lead to misapprehensions. Can you be inaccurately fluent? Perhaps only very occasionally. This may not seem important, but talk of fluency has the potential to send out all kinds of unhelpful messages. It is important to keep this in mind as the blog proceeds. It’s why the blog came into being. We are thrilled that the fluency renaissance is well underway, and we are doubly thrilled at the impact we have seen in so many schools in relation to our Fluency Project work. But we are also mindful that talk of reading fluency can be riddled with misconceptions. One of the driving forces behind this blog was a recognition that word has spread far, wide, and quickly in relation to fluency. But so, too, have some associated misapprehensions or misapplications.

We’ve also noted an increase in a focus on the methods (the ‘what’ as in ‘what is echo reading?’) over the rationale or justification behind their use (the ‘why’ or 'how' as in ‘why or how might echo reading be helpful?’). The word ‘might’ is significant here. Echo reading can be a very helpful strategy if used in a targeted way to develop expressive, phrased reading. But it can also be over-used if applied liberally at a whole class level. Worse still, it can sometimes mask fundamental difficulties or give a misleading picture of progress if it is being used to circumnavigate difficulties with decoding. Echo reading is not a short cut for when independent decoding is unsuccessful. You can find more on echo reading in the latter half of this blog.

What do we mean by reading fluency?

Given the scope for confusion, fragmentation, and misapplication mentioned above, it is important to define our terms clearly. The terms ‘fluency’ and ‘fluent’ are far from new in relation to reading and writing. They’ve been used to describe a range of linguistic behaviours. We speak of being fluent in particular languages and of being fluent writers, but what do we mean? Very often, when it comes to reading, fluency has been associated just with speed.

Reading fluency is now more commonly agreed to be made up of the following components:

- automaticity (rapid word reading without conscious decoding)

- accuracy (words read accurately, typically measured as a percentage)

- prosody ( expressive, phrased reading)

Let’s unpick these terms so that we are clear on why a good understanding of these concepts is important in developing fluent readers who are able to think and respond more effectively to what they read, as they read.

Automaticity (word recognition rates)

This refers to a level of experience and competency in relation to word reading that means that conscious decoding is no longer required for familiar words. Word reading is so rapid it effectively occurs on sight (hence the term sight words – words that are processed with minimal cognitive effort in a split second). Automaticity is key in that it frees up the cognitive space that would be used for low level processing of words. This means that more of our mental energies can be directed more effectively towards other activities ‘…such as comprehension, analysis, elaboration and deep understanding.’ (Hattie, 2014) In relation to fluency work, we are concerned primarily with oral reading speeds. It might well be argued that part of the reason for the above reported neglect of fluency in the recent past is that once a certain level of reading competency has been assumed, often marked by the shift to silent reading practice, there is a potential risk for nascent or emerging difficulties to go undetected. In the words of Seidenberg: ‘Children who struggle when reading aloud do not become good readers if left to read silently; their dysfluency merely becomes inaudible’ (2017. P130). As the complexity of reading materials increases, these masked issues will most likely be exacerbated.

As such, attention to oral reading fluency – or what Shanahan calls text reading fluency - is important. But a careful balance needs to be struck, both in terms of developing oral and silent reading, and also in terms of how we handle the development of rate. Where England has focused far more heavily on the development of systematic phonics instruction over the past 15 years or so, it could be argued that greater focus has been given to fluency and, within that, reading rate, in the US. From this focus, some cautionary tales emerge. If reading rate development and measurement is not sensitively handled, it could quite easily become an ill-advised race to achieve ever-faster rates. Reading too fast is not what we are aiming for with our strongest readers and is something that has often had to be addressed with overly speedy readers in our Fluency Project work. Beware too the peer worship of the class's speediest reader. To the children, they are acing this reading game. For the enquiring adult, they all too often struggle to show anything like the depth and range of understanding we might hope for. Conversely, we risk demotivating less confident readers if we set unrealistic targets or too overtly celebrate the achievements of the whizziest decoders. We are looking to support children to move towards a suitably paced rate when reading aloud an age-appropriate text. For our money, something around 120 WPM by the end of Year 4 rising to around 150 WPM by the end of Year 6 is a fairly good indicator. This reflects rates shared by Rasinski and Cheeseman Smith in their Megabook of Fluency (2018) as well as the Oral Reading Fluency data of Hasbrouk and Tindal (2017).

Of course, keeping Duke and Cartwright's (2021) messages relating to active reading in mind, reading rates should demonstrate a degree of flexibility for the increasingly strategic reader. If I am reading a favourite Anne Tyler novel, I’m whipping through it. My silent reading for pleasure will be markedly faster than my oral reading. Seidenberg describes this as a ‘technological advantage’ of reading – where the unnatural act of deriving meaning from printed words outstrips our natural processing capacities with spoken language. However, even when reading silently, if I am reading a pension letter – a field way out of my comfort zone and no doubt affected by my own motivation – I slow down. I go back over technical language, and I deploy a different, more deliberate set of reading gears that allow me greater traction with the words, and a better chance of understanding quite how bad my financial future might be looking. I alter my speed according to need.

As a closing tip, Seidenberg also points out that audiobooks are generally recorded at around this sweet spot of reading rate – typically around 120 to 150 WPM. So if you are looking to supplement your models of a good oral reading rate, audiobooks may just be worth a punt. Audiobooks can offer many of the other associated benefits of a good storytime session, too, if you choose well (text and the cast of readers).

Accuracy (word recognition and pronunciation)

Accuracy is inextricably bound up with automaticity. Appropriately paced reading is desirable but not at the expense of accuracy. Decoding errors and omissions will also impact upon the degree to which the text is read and understood. Any drive to improve the rate of reading has to attend to the level of accuracy that the reader achieves. Accuracy should develop as words become familiar. In the course of reading, skilled readers use context to support them in accurately reading homographs – words that are spelled in the same way but that have different pronunciations or meanings. This act of selecting the correct pronunciation to reflect meaning is one way by which we begin to see how fluency is an aspect of reading that straddles both word reading and comprehension. It is our knowledge of the word used in context that is tapped into to in order to inform the word’s pronunciation. I’ve written about this straddling previously. However, given that time is in short supply, I would urge you, instead to read this recent article by Duke and Cartwright (2021).

My admiration and excitement for this article is still at the boundless stage, and so a further, fuller blog is on the cards – likely to be on my own site, given the likelihood that I will froth about its usefulness and brilliant design. Why do I like it so? It’s open access; it’s serious about bridging research and practice and places practitioners at the heart of its rationale; it is expertly structured; it has a reading model that offers a comprehensive insight into active reading and the processes that straddle word reading and comprehension, as well as providing explanations for these as potential causes of reading difficulties. As such, it scratches so many itches for those of us who acknowledge the value of the Simple View of Reading, but are sometimes, perhaps often, frustrated by how the simplicity of that framework is misunderstood or misapplied in practice. Duke and Cartwright’s model of an active View of Reading reflects the Herts English team’s own driving forces in all of our fluency work. From the off we have been concerned with shifting reading from being a passive experience to an active joy, or ‘busy brain reading’ to borrow my colleague Penny’s phrase. Active reading informs the third strand of our preferred fluency definition: prosody.

Prosody (appropriate use of phrasing and expression)

As noted in relation to accuracy, but on a more consistent, integral basis, prosody links comprehension to the ways by which we read words aloud (and the associated ‘subvocalisation’ that occurs when we read in our heads). It’s important to understand that prosody not only reflects some level of comprehension, in playing a part in fluent reading, it supports further, deeper understanding. There is plenty to read on prosody. Perhaps our favourite article to share is Schwanenflugel and Flanagan Knapp’s The Music of Reading Aloud. It’s an article that has been shared by our Reading Fluency Project team on many occasions: its free to access and it’s a very satisfying (melodic even) read in its own right. Daniel Willingham gets similarly musical in The Reading Mind, with his talk of ‘the melody of speech’ (2017, p66), and the ways in which this melody carries information: emotion, tone, emphasis…and more. So this keying into the rhythms of speech is especially important in bridging word reading and comprehension. It’s also important from the point of view of diagnostic assessment. If the reading is flat, or monotone, we might need to unpick and address the degree to which meaning making has been activated. Prosody is meaning made audible and you may want to read our earliest blog on the topic, from Kirsten Snook, who offers some excellent gateways into this critical topic, and offers a perspective that take account of our younger readers: Do you sound good to listen to? (or ‘fluency: reading’s best-kept secret weapon’). In the blog, Kirsten offers what I still think is one of the most beautifully simple prompts for prosodic reading I have yet come across:

“The book is talking to us. If you were the book, how would you say this?”

Just to close this section, it is worth noting that there is a growing bank of evidence that extends our knowledge of the roots of prosodic sensitivity and the role this may play in the acquisition of word reading (for a taster, you may want to follow the Holliman reference towards the end of this blog). A consideration of that evidence base is beyond the reach of this blog, but we may just want to note that we have by no means exhausted our understanding of the ways in which complex processes overlap and link word reading and comprehension.

Developing comprehension

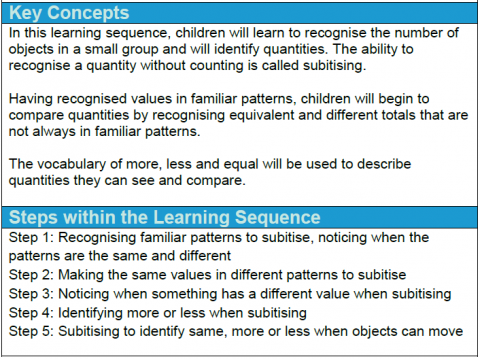

Developmental work to enhance these three aspects of reading fluency should be in service of greater comprehension of increasingly complex texts. Our initial work in developing the Fluency Project was heavily inspired by Professor Tim Rasinski, amongst others, and following their lead, was particularly geared towards children that did not present difficulties with word recognition, but struggled to comprehend texts that reflected an age-appropriate level of challenge. At the heart of our intervention work is an intention to improve reading comprehension. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that this aim, and gains seen in oral reading performance, has had wider benefits such as increased confidence and motivation to read. This is a highly desirable effect in that it becomes a driver for further improvements to reading performance. Returning to Duke and Cartwright’s recent paper, the authors suggest that influential models of reading such as Scarborough’s reading rope are in need of updating to reflect advances in our understanding of the processes that make up proficient reading. Central to this suggestion is the description of processes that straddle word reading and comprehension, and reading fluency is one of the processes described in this way. The authors also point out that a ‘growing body of research has demonstrated that skilled readers are highly active, strategic, and engaged, deploying executive skills to manage the reading process …Readers play a central role in making reading happen. In addition to acquiring necessary word-reading and language comprehension knowledge and skills, readers must learn to regulate themselves, actively coordinate the various processes and text elements necessary for successful reading, deploy strategies to ensure reading processes go smoothly, maintain motivation, and actively engage with text.’ (2021, p30)

This talk of agency, and associated executive skills is echoed in a blog from Shanahan also published this year. Exploring reading comprehension, Shanahan offers some pertinent insights:

‘What do I make of executive functioning?

Well, first it requires intentionality … it’s the part of our mind (not brain) that takes agency, that tries to accomplish things, that aims at goals. Too often we treat reading comprehension as if it operated mainly through automaticity — arising spontaneously from reading the words.

But to comprehend we must focus on the ideas. Research reveals that adults often “read” text without attention to meaning…

So here we have a note of caution. Yes, we want to develop fluency, but we need to maintain a focus on the real end goal of reading: understanding. Even if the reading sounds meaningful, we need to ensure that reading for meaning is our real aim. As such our Reading Fluency Project makes deliberate use of targeted questioning to ensure reading is active and strategic. Where the first session with a text is focused upon fluent reading performance, the follow up is always focused on comprehension of that text. Shanahan goes on to make a case for the role of challenging reads in this work in order to provide sufficient motivation to develop strategic reading, self-regulation and reflection. This too, is a key feature in the design of our Fluency Projects and you can find a range of links to previous blogs offering suggested texts for all phases:

Flexing fluency muscles with great texts (Oh…and they are free too!)

KS1 Reading Fluency Project: text selection guidance – Years 1 and 2

KS2 Reading Fluency project: text selection guidance – Years 3 & 4

KS2 Reading Fluency Project: text selection guidance

KS3 (Year 7) Reading Fluency Project: text selection guidance

Ways by which we might develop reading fluency

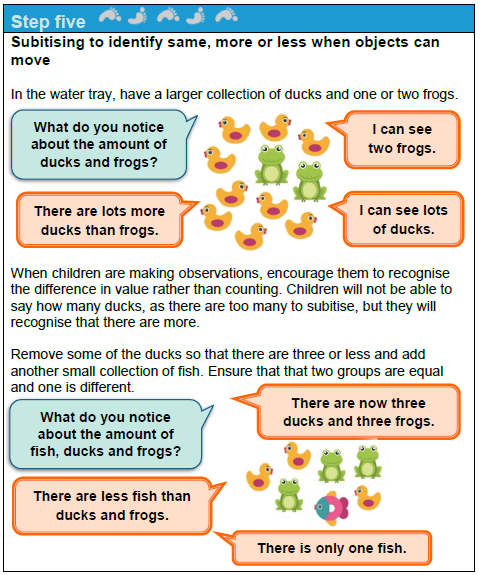

As part of our KS1 and KS2 Reading Toolkit, we offer a chapter devoted to fluency. This graphic offers a capsule summary of the core methods that we have been lucky enough to read about, explore, and refine in the course of our work.

As well as these listed approaches, paired and assisted reading have been shown to be very effective in developing fluent reading. Of the pictured approaches, echo reading seems to be causing the biggest buzz and deserves some special mention. Contrary to some recent reports, echo reading was not christened in 2021 – which is a good thing. Rather than worry ourselves about the possible limitations of a “fad of the week” type scenario, echo reading has a long and well-developed history, and has more and more empirical weight behind it. It is not new, nor is it the only strategy or approach that we might use as part of our reading fluency development work. Like other aspects of reading, two rules of thumb are helpful:

- use of a limited range of development techniques means that more time can be devoted to practice, as there is not a need to spend additional time on explaining unfamiliar activities for our learners. It also allows practitioners to develop expertise in the delivery of these methods, and supports increasingly responsive teaching. The processes (for example, echo reading, paired/assisted reading, text marking, choral reading) are staples; the reading materials are novel and our part of the deal is to provide rich, diverse, engaging, and motivating, challenging material to help us develop proficiency as efficiently as possible.

- instructional approaches should be targeted to need and designed to have good effect. The vehicle, or approach or strategy (the what) is less important than the desired outcome and how effectively we support our learners to achieve it (the why). What really matters above all is improved outcomes in terms of reading performance, confidence and motivation.

Further reading

As I said somewhere above and seemingly years ago, there is so much more to be said on the subject. I’ve barely scratched the surface. However, in order to make good on a stated promise on Twitter to provide a comprehensive reading fluency digest, the following suggestions for further reading should be sufficient to keep even the most hardened reading teacher going across the summer. Now that I've made good on my promise of a digest, this particular blog will be refreshed with newer signposts/links as more content is added.

Below you will find:

- links to all of our blogs on this topic with a brief summary of content. For your ease, I have grouped these under clear, and logical sections beginning with an opportunity to join us to hear more, then links to blogs offering our reasoning for our investment in fluency work, as well as our methods, outcomes and suggested texts for class use

- helpful websites or reports/guidance that situate fluency work as part of effective reading instruction provision

- accessible introductions to fluency or to the importance of fluency within the reading act and/or the importance of reading fluency development within our practice

- more in-depth looks at fluency – open access/free to download

- research articles or published books that offer deep insights but that require some form of payment

Why fluency matters

Do you sound good to listen to? (or ‘fluency: reading’s best-kept secret weapon’)

A key early primer that looks at how reading fluency is commonly defined and that goes on to provide a very clear rationale as to why reading fluency needed greater attention as part of our collective drive to improve reading achievement

As easy as A B fluenCy!

An early account of some class-based exploration arising from the release of the DfE’s 2016 working at ARE videos and following research work in support of the development of our EY/KS1 and KS2 reading guidance toolkits

What do we mean when we talk about reading (and writing) fluency?

A gathering of thoughts from workshop sessions delivered (at the ResearchEd National Conference & Oxford Reading Spree in 2019). These sessions looked in particular at how reading fluency spans both dimensions of the Simple View of Reading – something more fully and helpfully explored in Duke & Cartwright’s Active View of Reading (2021, see discussion above) - and were concerned with the integration of multiple processes in the act of meaningful/meaning-led reading.

Comprehensive summaries

The Herts for Learning (HfL) KS2 Reading Fluency Project – strategies and outcomes

An overview of the various iterations of the KS2 Reading Fluency Project. This comprehensive read offers observations related to the drivers of our work in this field, as well as helpful notes on where the intervention strategies proved most helpful.

Fluency: the bridge from phonics to comprehension

A short and sharp collection of notes taken from Tim Rasinki’s keynote session at our Fluency Expo! Conference, January 2021.

What we do in our fluency project – approaches and strategies

Read like nobody is watching

A comprehensive, and highly practical collection of hints and tips to develop active reading. A good read to follow Duke & Cartwright’s (2021) global look at reading.

Outcomes and impact

Early findings from the KS2 reading fluency project

Some hints and tips and early observations from the first iteration of our KS2 Reading Fluency Project

Repeat after me: the HfL KS2 reading fluency project works… works… works!

This is a summary of later findings from the very successful rounds of the project delivered across a wide range of schools. In amongst the findings, you will find some very helpful key pointers. One such pointer is the importance of carefully calibrated use of ‘echo reading’ as one strategy amongst a range of approaches designed to enhance confident, meaningful reading. It needs to be used strategically. ‘Echo reading’ seems to be a particular strand that has generated quite a buzz. As sometimes happens when practice achieves a trend state, it can get warped out of shape. We’d just like to draw attention to some key messages:

Wider reading

Open access papers, articles and blogs

Duke, N., Alessandra, E,. David Ward, P. The Science of Reading Comprehension Instruction, The Reading Teacher, Vol 74, No. 6, pp.663-672

EEF (2017) Improving Literacy in Key Stage Two Guidance Report

Heitin (2015) Literacy Expert: Weak Readers Lack Fluency, Not Critical Thinking

Heitin (2015) Reading Fluency Viewed as Neglected Skill, Education Week

Holliman, A. J., Mundy, I.R., Wade-Woolley, L.W., Wood, C. & Bird, C. (2017) Prosodic Awareness and children’s multisyllabic word reading. Educational Psychology, 37:10, pp1222-1241

Kuhn, S. & Stahl, M.R. (2003) Fluency: A Review of Developmental and Remedial Practices, Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 pp.3-21

Lofflin, K (2012) offers critical reflections on Marcell, B. (2011) Putting Fluency on a Fitness Plan, The Reading Teacher Vol 65 issue 4 (see ‘paid for’ reading list below)

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000) Report of the National Reading Panel; Teaching Children to Read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction, US government Printing Office

Rasinski (2012) Why Reading Fluency Should be Hot!, The Reading Teacher Vol 65 Issue 8

Rasinski, T. Yildirim, K. & Nageldinger, J. (2011) Building Fluency Through the Phrased Text Lesson, The Reading Teacher Vol 65 issue 4

Rasinski, T. (2014) Delivering Supportive Fluency Instruction, Reading Today

Schwanenflugel, P.J. & Flanagan Knapp, N. (2017) The Music of Reading Aloud

Shanahan, T. (2017) How to teach fluency so it takes

Published books, academic subscription or purchase/rental only

- Dowhower, S.L. (1994) Repeated Reading Revisited: Research Into Practice, Reading and Writing Quarterly, 10

- Dowhower, S.L. (1991) Speaking of prosody: Fluency's unattended bedfellow, Theory Into Practice, 30:3, 165-175

- Klauda, S.L. & Guthrie, J.T. (2008) Relationships of Three Components of Reading Fluency to Reading Comprehension, Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 100, No. 2, 310–321

- LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, 293-323

- Marcell, B. (2011) Putting Fluency on a Fitness Plan, The Reading Teacher Vol 65 issue 4

- Miller, J. & Schwanenflugel, P.J. (2006) Prosody of Syntactically Complex Sentences in the Oral Reading of Young Children, Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 98, No. 4, 839–853

- Rasinski,T. & Nageldinger, J.K. (2016) The Fluency Factor: Authentic Instruction and Assessment for Reading Success in the Common Core Classroom, Teachers College Press

- Rasinski, T., Homan, S. & Biggs, M. (2009) Teaching Reading Fluency to Struggling Readers: Method, Materials, and Evidence, Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25:2-3, pp. 192-204

- Samuels, S.J. (1979). The Method of Repeated Readings The Reading Teacher, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 403-408

- Stahl, S.A. & Kuhn, M.R. (2002) Making it sound like language: Developing fluency, The Reading Teacher; Mar 2002; 55, 6; pg. 582

- Therrien, W. J. (2004). Fluency and Comprehension Gains as a Result of Repeated Reading: A Meta-Analysis. Remedial and Special Education, 25(4), 252–261

Reading Fluency Project Page

Links to further information relating to our KS1, KS2, and KS3 Reading Fluency Projects.