Reflections from analysis of the 2019 KS2 reading SATs: part 2

Analysis of the papers can take many angles and I don’t hope to cover them all in this series of blogs; instead, I intend to use an analysis of the reading SATs to allow for insights into our current teaching practices in the hope of developing and sharpening classroom pedagogy.

If I miss anything of particular interest, please do get in touch, and I will try to explore that avenue.

Inference – there’s more to it than meets the eye!

I have long since stopped the (to my mind) fruitless task of analysing past papers to see which tested domain presented the area of greatest weakness for my pupils. Following several years of laboured analysis, I realised that I was reaching the same, rather unhelpful conclusion: the children struggle most with questions relating to inference (tested domain 2d).

I now see that there are several reasons for this: firstly, it tends to be one of the most heavily tested domains; secondly, the question format tends to be the most challenging, in that the questions tend not to fall into the easier ‘tick a box’ type response. Clearly, if a domain is heavily represented in a test, then it is more likely that at some point children will make an error or two on one of the many questions within this sub-set, therefore making it likely to look like an area of weakness. To exemplify this point, let us turn to the figures…

In 2019, inference remained a testing domain heavy-weight, commanding 18 of the potential 50 marks from the test! Compare it to domain 2c (which tests the ability to summarise) - which was allocated a measly 1-mark question across all three texts - and you begin to get a sense of the weighting.

If this weighting is taken too literally however, misinterpretations begin to form: if not careful, we may form a skewed perspective on how the testing domains relate to potential classroom teaching of reading. The weighting analysis could lead us to conclude that teaching ‘inference’ is more important than teaching ‘summarising’, after all, it appears that the children will need to flex their inference muscles a great deal more than their summarising ones.

Instead, it is helpful to step back and remind ourselves of the bigger picture, and specifically how the reading skills required to make inferences might marry together. To support with this, I refer you to a well-aged blog, published back in 2016 entitled Reading Re-envisaged, where we explored the potentially interrelated skills of reading comprehension. When considered in this way, we can see that the ability to summarise is an essential skill in allowing inference to flourish, not a mere by-stander in the comprehension process. Therefore, neglecting the teaching of ‘summarising’ in favour of teaching ‘inference’ is not going to win any marks in the long-run.

The message here then is that extrapolating insights from the reading tests, and using them to directly shape and guide classroom pedagogy, can be short-sighted and can lead to reductive teaching practices (the example here being that of the weighting towards inference questions: just because inference is tested more, it doesn’t mean that we should isolate this skill and try and teach it). Instead, we need to think wisely about the errors or gaps that we see displayed before us and respond in a measured and informed manner, bringing to the fore our understanding of what it takes to become a skilled reader.

Most often, the solution will be to provide holistic, rounded and well-informed reading guidance, allowing room for plenty of teacher modelling and pupil practice of a wide range of skills, using a wide range of quality texts, rather than honing in on domain specific questioning. Of course, this doesn’t provide a quick route to reading proficiency, but it certainly provides the most successful one.

It’s Vocab, Jim (but not as we know it!)

Another ‘hidden’ tested domain relates to vocabulary. Although according to the test mark scheme, only 6 marks were accredited to questions listed as testing domain 2a (‘give/explain the meaning of words in context’), as teachers, we know that word knowledge, and specifically vocabulary breadth, is fundamental to reading comprehension success. As the model of comprehension referenced earlier denotes, if you don’t know the meaning of the words on the page then you have great difficulty moving across to the outer circle of the comprehension model.

Every question within the test assessed proficiency within domain 2a. I am no doubt preaching to the converted when I state that vocabulary exploration and development must underpin everything that we do. Its power to support - and impede - the young reader cannot be understated.

Seeing as vocabulary knowledge and breadth is pivotal to reading comprehension, it is worth looking in depth at some of the questions in the 2019 paper relating to this domain, in order to gain an insight into the children’s strengths and weakness in this area. Indeed, a closer inspection of the question styles, and the data outcomes, does reveal something that may be helpful for guiding our classroom practices.

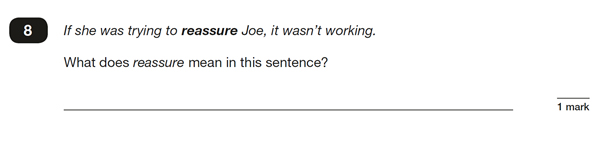

One of the most poorly answered questions, pertaining to texts 1 & 2, was question 8 (a lowly 65% correct national response rate). Question 8 is presented below.

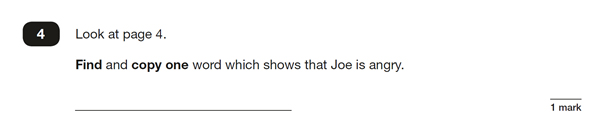

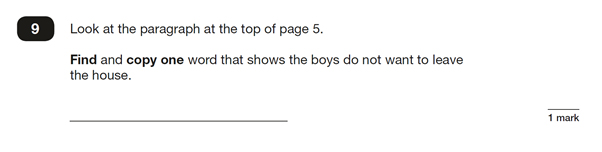

If your children – like those nationally - stumbled over this question, then you may have reached the concluded that they struggle with word knowledge. As a responsible teacher, you may already be setting to work thinking about how you could address this area of supposed weakness. But, hold on! There may be more to this than meets the eye. There were two other questions pertaining to domain 2a within the question set for text 1 (question 4 & question 9) – both are represented below.

At a national level, both these questions received significantly higher correct response rates than question 8 (Qu.4 = 95.1%; Qu.9 = 92% correct response) with the vast majority of children who had a go at the questions getting them right. The challenge then appears to be less about poor word knowledge per se and more about an issue with question style. If you had already set to work to resolve this issue by introducing more ‘copy and find’ style questions into your repertoire, you are unlikely to solve the issue. In fact, most children seemed ok with this style of thinking and questioning. Instead, what they struggled with was the ‘explaining’ element required by test question 8.

Most teachers would acknowledge that the ability to ‘explain’ is far trickier that the ability to ‘spot’. Knowing this should therefore guide our practice towards creating learning opportunities that develop the art of explaining language meaning, rather than simply spotting synonyms. In reality, this means planning activities that allow children opportunities to explore language in context; allowing them time to tease out alternative meanings and to attribute the most likely one to the text in hand; to debate the nuances of language and then, most importantly (from a test situation perspective at least), to learn how to encapsulate this understanding into a pithy explanation or definition. This, you can see, is a very different approach to one which might have led to adapting some paper-based comprehension task to incorporate more generic domain 2-type questions.

The key to developing improved responses to question 8 – and others like it - will be achieved through regular well-planned language discussion, based on a wide range of quality texts, not through silo working on well-intentioned comprehension exercises.

The journey required to achieve this deep knowledge of words and language is undoubtedly longer, but ultimately, when dealing with vocabulary development, we have to recognise that we are in the business of securing long-term gains, rather than short-term wins.

I hope that this blog provides enough to get teachers thinking about some of the ways in which they might interpret the findings of this year’s reading SATs paper outcomes, and how their findings might be translated into effective classroom pedagogy.

The holes that Stanley has to dig have to be exactly the same size as his shovel – his shovel is 5 feet (150cm) long.

The holes that Stanley has to dig have to be exactly the same size as his shovel – his shovel is 5 feet (150cm) long.

STRETCH!

STRETCH!

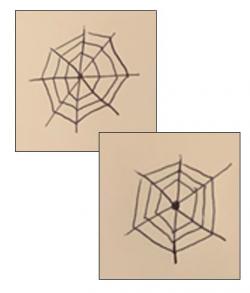

Have you ever looked closely at a spider’s web to see how beautifully they are structured and the patterns that they create? I have drawn 2 of my own webs based on Charlotte’s.

Have you ever looked closely at a spider’s web to see how beautifully they are structured and the patterns that they create? I have drawn 2 of my own webs based on Charlotte’s.

Ladybirds are a type of beetle. They have six legs and two sets of wings. Some ladybirds have no spots and others have up to 20 spots.

Ladybirds are a type of beetle. They have six legs and two sets of wings. Some ladybirds have no spots and others have up to 20 spots. this lunch box is designed using food from one of the lunches in the story that Mrs Grinling sends to Mr Grinling

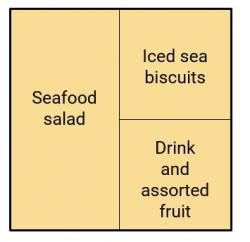

this lunch box is designed using food from one of the lunches in the story that Mrs Grinling sends to Mr Grinling