September: return to work; note the chill in the air; resist the urge to swap too many anxiety dream stories; present at ResearchEd. Those last two may be related .

Last year I had the privilege of presenting at the ResearchEd national conference with Megan Dixon (@DamsonEd) and the sadness of not presenting with Sinéad Gaffney (@shinpad1), our absent co-author. There we considered the dominant approaches to reading instruction in primary schools, weighed them up against each other, and found that they are all quite handy actually. We are rather keen on this outcome. It’s comfortingly old fashioned for teachers to have a range of teaching approaches to draw upon as they refine their instincts and make the daily choices that only they can make. The year before that I had spoken about reading and grammar and the links cover those sessions sufficiently well to be getting on with.

This year, my session was titled 'What do we mean when we talk about reading (and writing) fluency?' The session took as its focus the following key strands:

- defining reading and exploring some conceptual frameworks that begin to account for the underlying/constituent processes that come together in proficient reading and on the journey towards it;

- a brief and tentative exploration of some of the potential causal factors in dysfluent reading;

- a brief, far less tentative exploration of how policy and online discussion of reading can sometimes be less helpful than intended;

- a recap and update on what we mean by reading fluency, why subtle distinctions in how this is defined can have serious consequences, and some suggested approaches and reading to support the development of fluent reading;

- a discussion of some recent work exploring how to make the links between reading and writing more seamless for our students, so that work on reading fluency more efficiently informs work on writing development – composition and authorial intent in particular.

There are too many slides to share here – it really was a packed session – so I have cherry picked those that are either central, or that seemed to draw a lot of interest. For the sake of space-saving, I have grouped slides and then provide a short commentary below them. Please feel free to get in touch if you would like further details or a PDF with a more comprehensive set of slide images.

The session began with introductions and a credit to key collaborators and fellow reading warriors Megan and Sinéad who have done much of the thinking that informs so much of this work. It’s important to credit, especially in reading where messages sometimes seem to be bent out of shape almost as quickly as efficient word reading.

As in all the sessions that I share with Megan and Sinead, reading was defined to some degree here, as that seemingly simple term (“it’s just reading, isn’t it?”) can mean different things, in different contexts, and according to different perspectives. Note the shared thread of complexity: Stuart and Stainthorp take care from the outset of their book to make clear that whilst key components of reading are necessarily outlined and discussed in isolation, reading is an integrative act. Think of Scarborough’s reading rope and the way that it cleverly illustrates the increasingly interwoven threads of reading as the developing reader moves towards proficiency.

Incidentally, Stuart and Stainthorp’s book is an extremely helpful title, which really should be receiving more recommendations, relative to some of the books enjoying greater currency on Twitter and other platforms, particularly given its attention to the whole journey of learning to read. Also recommended is the paper cited in the right-hand slide, a well-structured and comprehensive overview of much of the most up-to-date thinking around reading.

Given its influence in the literature, and in the way that it underpins the curriculum, there had to be a discussion of the Simple View of Reading (SVoR). First, we explored how the SVoR works as a conceptual framework. We discussed how there are two components at play – language comprehension processes and word recognition skills – and that both have to be at play for reading to happen. It is a multiplicative model. If one aspect is missing, the effect of multiplying by 0 holds true here. The act of reading, as defined for the purposes of this session, has to include both the act of decoding words (or "lifting them off the page” as often seems to be said) and understanding what the words, phrases, clauses, sentences (or lines and verses, say) come together to mean. I have tried to word that carefully, but I am equally mindful that this is a blog and not an essay. A significant part of my 2017 session was spent on exploring how much mental work is going on in order to read the words, integrate meanings across word and phrases, and then to make similar links across sequences of sentences, across sections or paragraphs, and ultimately across texts. It should never be forgotten quite how staggering this routine achievement of reading actually is in terms of human evolution. Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid remains possibly the most beautifully written account of reading, in these terms.

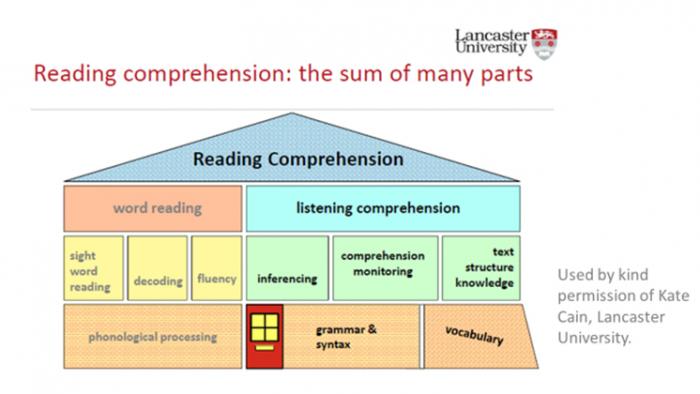

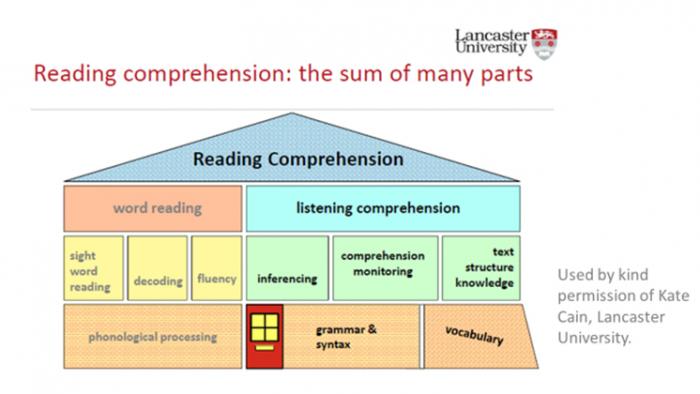

To further dig deeper into reading, Kate Cain’s very helpful diagram was used. Megan, Sinead, and I particularly like to use this model as it is non-threatening (some diagrammatic representations of reading are not so digestible on first sight) and more particularly, because it works with the simple view of reading . Note the top floor of the house. However, this representation is carefully constructed to work up from the ground floor with the implicit understanding that each successive storey rests on those lower down. No ground floor? You won’t get a good night’s sleep in the upstairs bedrooms.

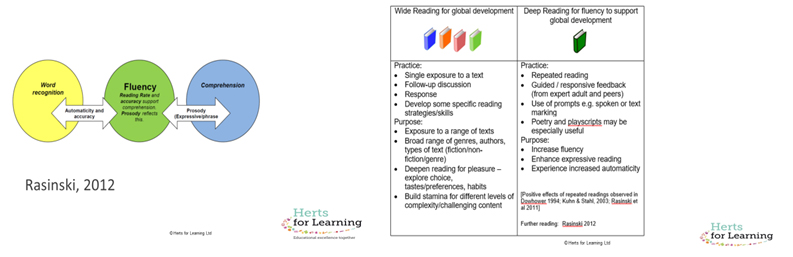

I’ve spent too long thinking about the Simple View of Reading over the past four years. In the course of that thinking, I have been able to observe less-than-effective reading practice that, on occasion, has happened because of the simplicity of the framework. There is a surprising degree of scope for misapprehension. Simple is sometimes best; sometimes it is simply misunderstood. Rather than take up too much more space on this here, let me get to my central point. We want as many of our children to achieve fluent reading as humanly possible, and as efficiently as possible. It is increasingly agreed now that fluency is not simply rate and/or accuracy, but also incorporates expressive, phrased reading. That is, the reader demonstrates prosodic awareness and in doing so attends to meaning as they read, adapting the way in which words (and word parts) are stressed, grouped, pitched and more, to reflect the dynamics of spoken language and, where necessary, the voice that is called for in the sad part of a story, or in delivering an important speech.

Or the breathlessness of a packed ResearcEd session.

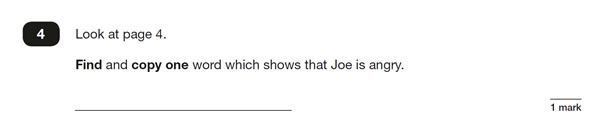

If fluency rests on an appropriate pace, and accuracy – often discussed as components of word reading – as well as prosody – more obviously related to meaning - then fluency extends across both dimensions of the Simple View of Reading. I’ve tried to represent what I mean here:

The yellow arrow indicates how fluency is often discussed but even here we have a problem. To be fully accurate in terms of pronunciation (or phonological representation) of homographs (words with the same spelling, but different sound patterns and meanings) we often need to draw upon the context in order to read the word accurately. So for example: “To read this carefully will lead you to rhyme ‘read’ and ‘lead’ with need”. That use of context or syntax forces us beautifully, and hopefully, smoothly into the realm of language comprehension, and ideally, language comprehension on-the-run so that reading is smooth, responsive and only occasionally needs a “go back and check that bit” moment. To wrap up this section, it might mean that the fluency ‘room’ in Professor Cain’s house might need to be extended into the ‘Language Comprehension wing’ depending on how fluency is being defined.

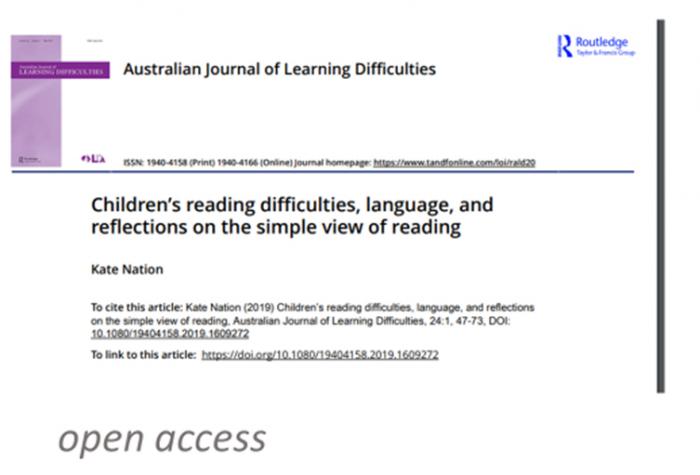

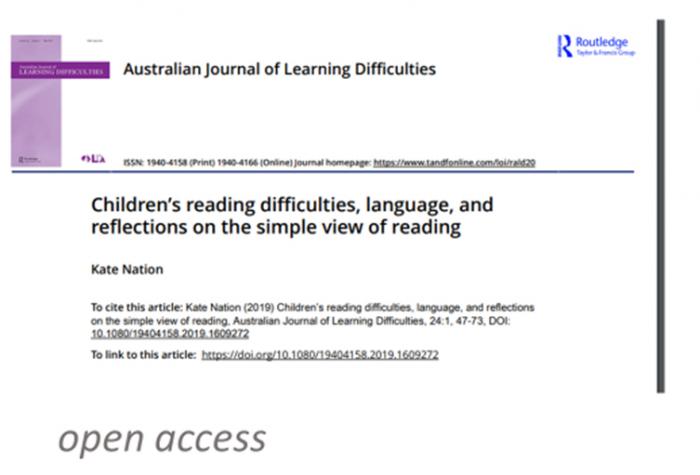

I would just now like to share a link to a paper by Kate Nation that is happily available for free access and that goes into far richer detail about why the Simple View of Reading may benefit from a degree more complexity: www.tandfonline.com/. Let’s just say this paper has scratched some longstanding itches, and move on.

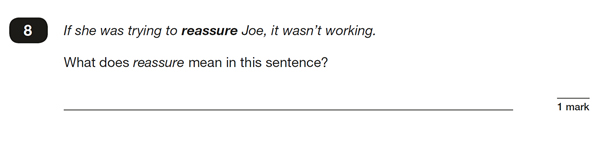

The next section explored the research around difficulties in comprehension. This is a complex area that I cannot hope to do any kind of justice to here. However, I would flag that all too often, those that might be vulnerable to comprehension difficulties are not identified until texts become sufficiently complex and require integration of more elements, of increasing complexity. It worries me a great deal when I read that you 'cannot teach comprehension' on social media. I think that is hard to argue with if you take that statement very literally. Comprehension is the product of reading and you cannot directly teach what form(s) that takes, or doesn't take, in the reader's mind. Nor should we. Reading is not the transfer of a single idea or interpretation from writer to text, text to reader. These impressions, or the gist, or the mental model to be more complete, sit, unhelpfully or helpfully depending on each reading experience, in the reader's mind. We can try to dig it out, unearth it, bring it to the surface, but our tools are not always as sharp as we would like them to be and things can be lost, distorted, or broken in the process of excavation. There is also the issue around what we even mean when we use the term 'comprehension'. Are we talking about what a reader comes to understand of a text, or something even bigger? Less helpfully, are we talking about a form of reading exercise, much like SATs, in which reading is followed by a series of questions, often organised to reflect assessment domains?

If we are talking about the latter, we may not be attending to the sorts of activity that help to develop confident, actively responsive readers. Wayne Tennent has spoken and written (see his 2015 book) on the tensions between where research suggests we might best direct our energies, and where energies are often directed largely due to the messages inferred from accountability measures for reading. I discussed this tension in the session: how we should look towards developing 'automatic' or 'online' inference-making (occurring in the act, across a given text) over 'controlled' or 'offline' inference-making, promoted by exercises that occur once the reading is done, such as a SATs style practice exercise. Back to my concerns about whether or not we can 'teach comprehension'. We could discuss this over the course of endless blogs, but life is short, and blogs are meant to be too. However, there are plenty of things that we can do to support those that might, or do, struggle with comprehension and I worry that we might sideline these needs in pursuit of yet another simplistic view of reading. Having said all of that, we turned to the practical. One such aspect of our work that should be supportive of enhanced comprehension is to work to develop fluent reading and to provide opportunities to experience what it is to read with fluency.

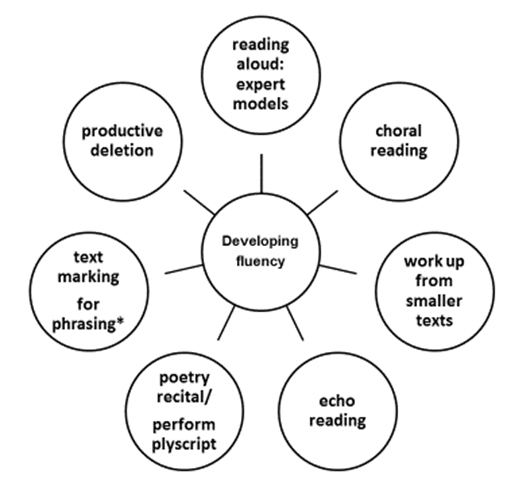

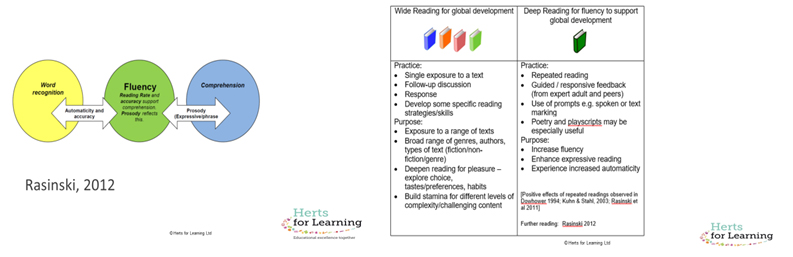

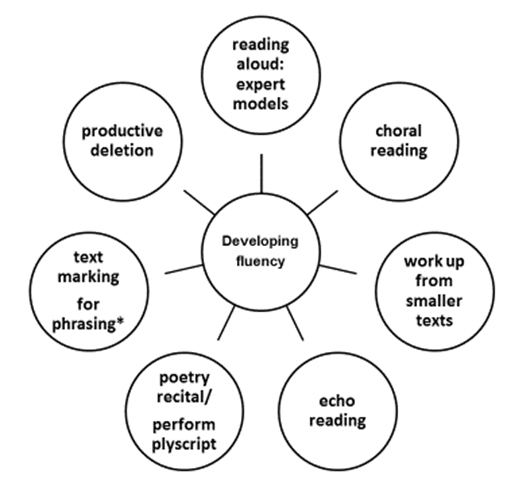

In order to provide practical solutions, the slides above formed part of a longer suite of around 12 slides that were used to explore time and cost-efficient strategies for developing fluency in reading. We deliver a range of exciting Reading Fluency CPD and projects now across KS1, KS2 and KS3. You can find out more details here. Some of the headline approaches are detailed below.

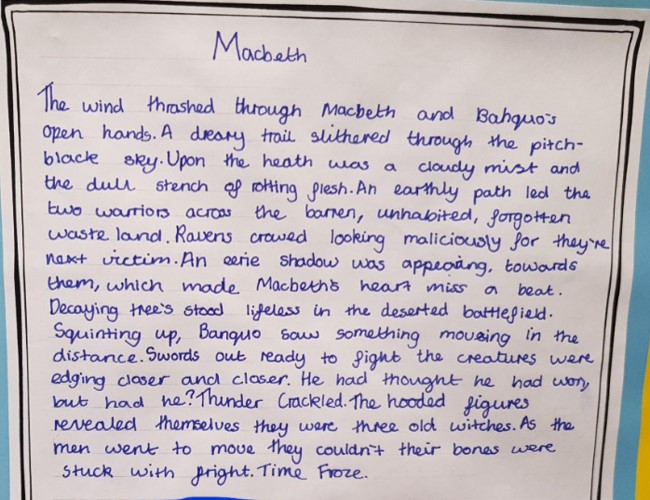

The session then moved on to explore some of my more recent work on the links between what we can learn from some explicit work on reading fluency, and how this might complement our work on writing composition.

As you can see from the top left slide, I have adopted the Möbius strip as a symbol of the seamlessness with which we want the development of skills, knowledge, and understanding in both reading and writing to inform each other. They are inextricably linked, reciprocal sets of processes and are both shot through with language learning. Yet some children (and adults) are quick to decouple them to varying degrees without realising that they have done so. One of the propositions of the session was that perhaps we could take what we have learnt from our work in developing fluency (read it like you mean it) and then take a step back further to ask our young writers to consider the needs of their intended reader (write like you mean them to read it). Donald Grave’s once referred to “selfish” writers and asked that we work to guide the development of “selfless writers”. Writers that keep their intended audiences firmly in mind, not just in terms of sometimes tokenistic, or even statutory talk of ‘audience’ and ‘purpose’ but in terms of envisioning how the reader will be served, or toyed with, or manipulated, or informed, or simply kept interested. In this, it also builds on a programme of extended CPD that my colleague Jane and I have been developing.

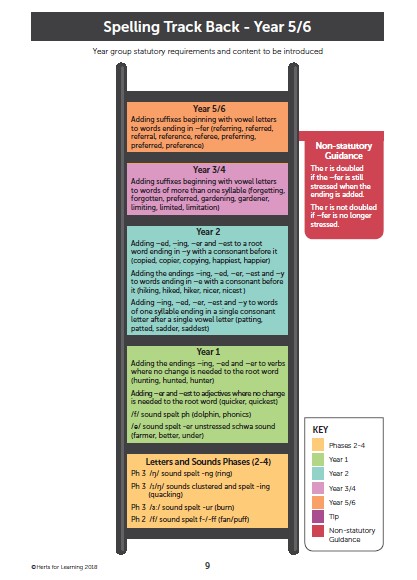

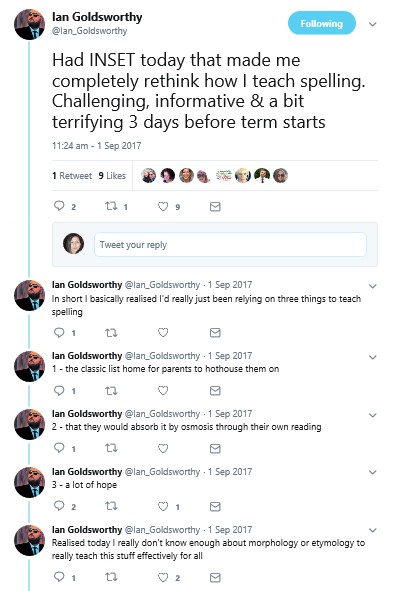

Back to the ResearchEd session, the slides acknowledge the importance of developing automaticity in both spelling and handwriting, if only in terms of motivation to write. Please note these are huge factors for many, if not most, reluctant or wary writers. The central theme I then went on to develop related to chronology and cohesion, and how some carefully sequenced work on these aspects of writing might help to develop our young writer’s own sense of what it feels like to write fluid text.

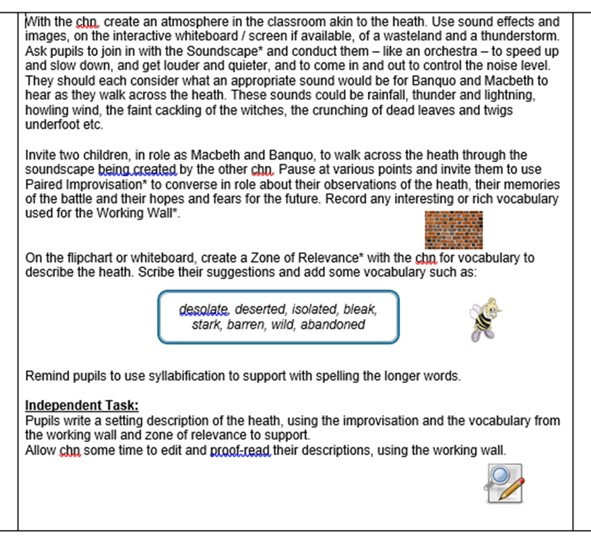

As in some of my earlier blogs, the influence of Myra Barr’s and Valerie Cork’s The Reader in the Writer (CLPE, 2001) extends into this work. One aspect of this influence manifests in the encouragement to focus not just on a linear written journey from A to B to C, but a journey that might meander (purposefully of course) forwards, backwards, or sideways in time. Or that perhaps lingers just a little longer here or there, providing the right kinds of detail and space for the reader to conjure up a more fully realised mental model that draws upon fluent skilled reading: making inferences, speculating, and receiving cues: this is a sinister part – please whisper; this is action – please shift gear. As such, we have strayed into the endlessly fascinating realm of narratology. We also talked about some of the science involved in negotiating such ideas as readers, but this blog has probably more than outstayed its welcome.

I wish I could spend longer outlining what we covered in the session but I am heading towards a deadly word count. If you have unresolved questions or points that require further clarification, please do get in touch with the Primary English team.