School governance – what’s the focus?

Ofsted

If you are in the window for an inspection this academic year then any inspection will be under the current September 2024 Education Inspection Framework (EIF) where the single word judgement has been removed. Simply put if you are due an ungraded inspection the focus will be on whether you have taken effective action to maintain standards since the last inspection. The report will explain whether you have maintained standards since, improved significantly since or may not be as strong as at the time of the last inspection (a fourth covers where a school is deemed inadequate in one or more judgement areas or there are serious concerns). Schools would use the full wording of these 4 possible outcomes to communicate their inspection outcome. Alternatively, if you are due a graded inspection, then you will receive a new set of 4 judgements (Quality of education, Behaviour & attitudes, Personal development and Leadership & management + where applicable EYFS and sixth form provision) which will replace your previous single word judgement, which you will no longer be able to use. Meanwhile Ofsted are working on a new EIF for September ’25, this will be subject to consultation (we think in the new year) and may centre around a new colour coded ‘evaluation scale’ from ‘causing concern’ through to ‘exemplary’ based on a report card that will possibly look at 10 judgement criteria.

This is a useful summary of the current EIF changes: Gov.UK: summary of changes

SEND provision

There is now a national debate, led by the DfE, looking into the multiple challenges, failings and blockers that are daily impacting on the lives, and life chances, of our most vulnerable students and what the solutions may be. As governors we are all too aware of the impact this has in our own schools and now is at least a chance to challenge the thinking and practice regarding SEND provision, though one thing that pretty much all are agreed upon is that it will take well targeted and new resource to even begin to right this particular ship. I think it’s fair to say that most, if not all, local authorities are facing huge challenges around SEND provision, and as demand inexorably rises for specialist provision and EHCPs, time is running out to address this.

A useful article from the Local Government Association covers the parliamentary debate on SEND in September and their plans for reform: Local Government Association: debate on SEND provision, House of Commons, 5 September 2024

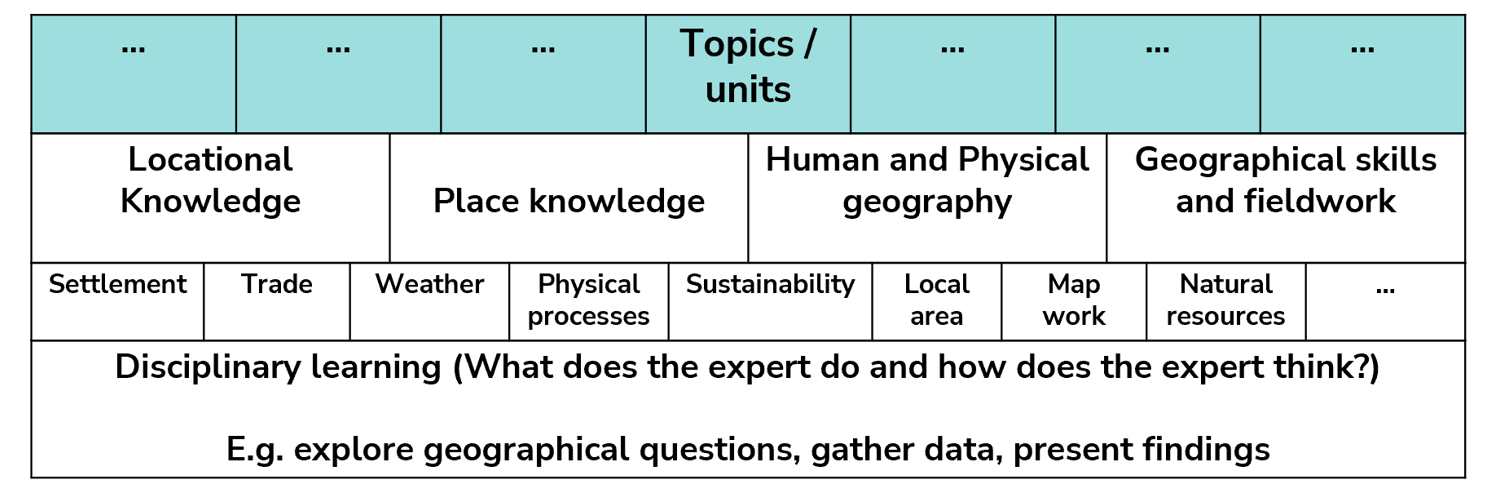

Curriculum review

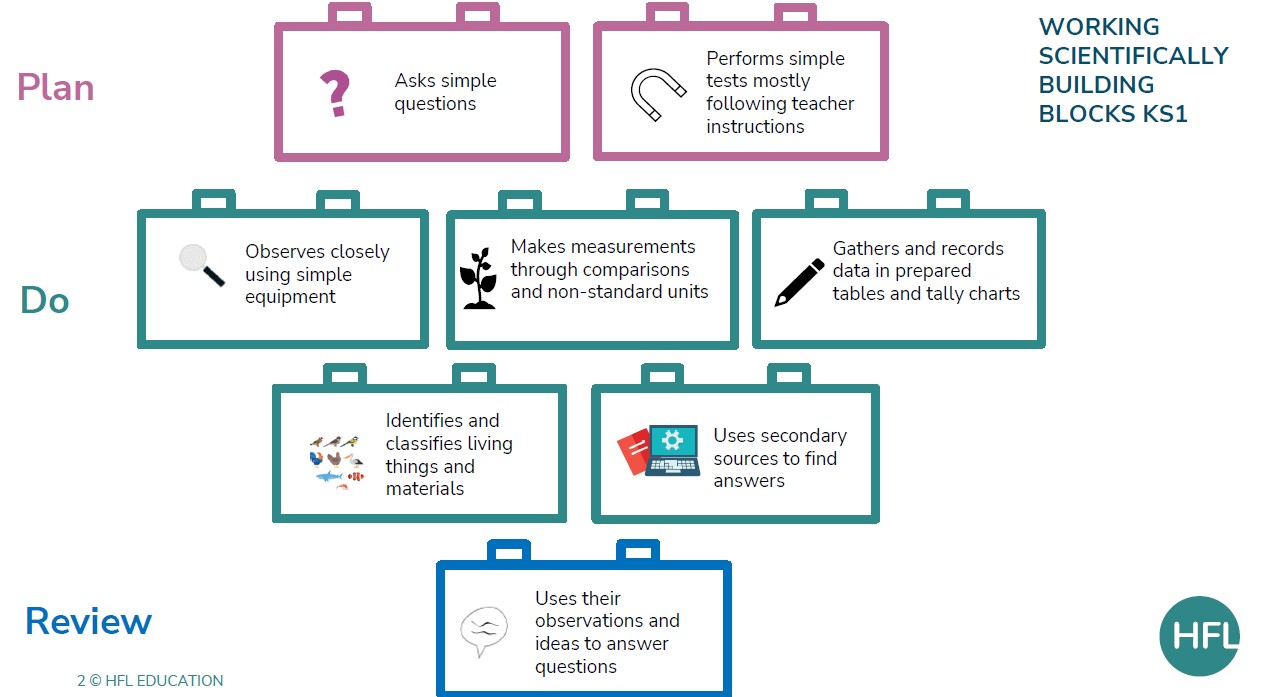

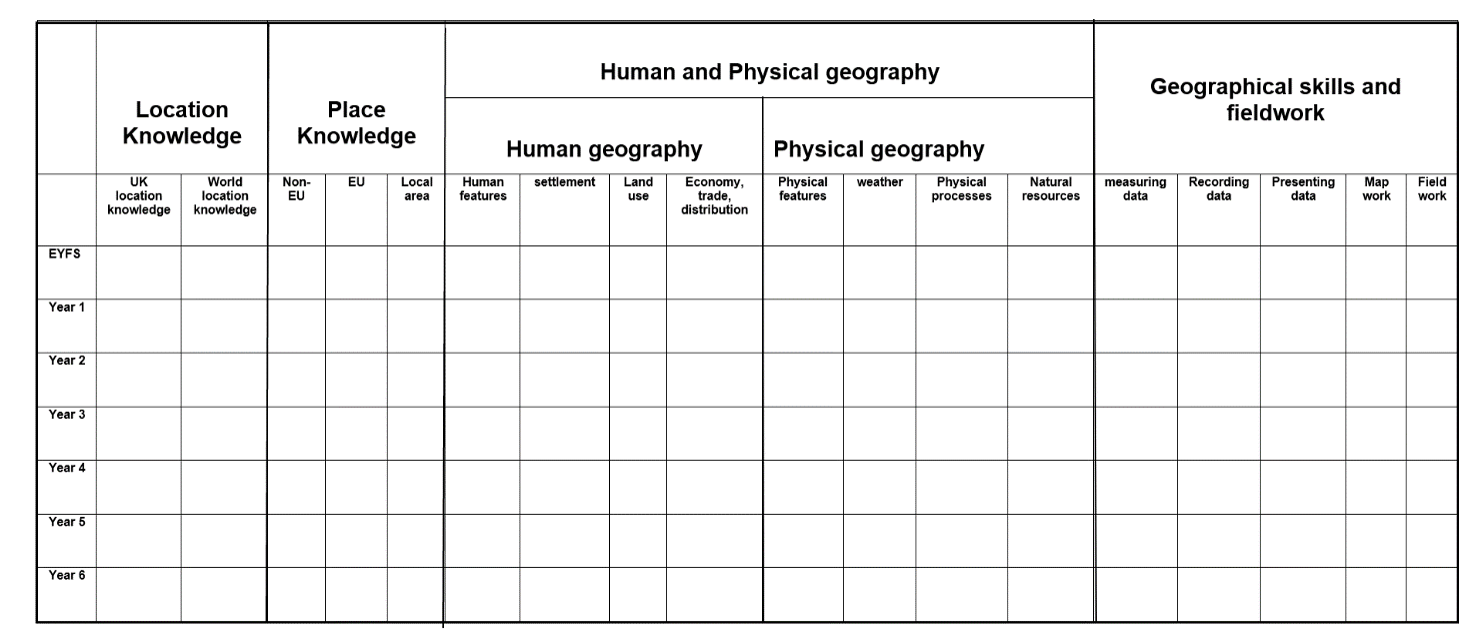

The call for evidence has now closed but earlier this term the DfE launched a review seeking the views of education sector experts and teachers as well as parents and pupils. The review spans Key Stages 1 to 5 and aims to ensure ‘the curriculum balances ambition, relevance, flexibility and inclusivity for all children and young people.’ An interim report will be published early in 2025, presumably for a further period of consultation, with the final report expected autumn 2025. As governors we will need to be alert to this and hopefully will be part of any interim consultation – our role in ensuring, not only that our schools meet the statutory requirements for delivering the curriculum, but also that it’s relevant to our setting and its vision and meets the needs of all pupils.

A bit more behind the thinking of the review: Gov.UK: What is the Curriculum and Assessment Review and how will it impact my child's education?

Suspensions

It’s very clear from national data that exclusions and suspensions are on the rise with significant increases in primary schools as well. Recent data from the DfE, analysed by the BBC, shows that there were 37,000 suspensions in primary schools in the autumn term 2023 which is almost as many as there were in the entire academic year 2012/13. This rise in school suspensions is clearly of great concern nationally but also at a school level where school leaders grapple with suspension decisions and governors try to understand the trends, what mitigations are in place to manage and reduce suspensions plus dealing with an increasing number of parental representations leading to an increase workload for governors having to consider these. The pupils affected are disproportionately those from vulnerable groups including those with SEND, from disadvantaged backgrounds and those who receive free school meals – the link between suspensions & exclusions and poor outcomes and life opportunities, often with unmet mental health conditions, just compounds the challenge for governors and school leaders. For all governors and trustees, being trained is an essential prerequisite to be able to effectively challenge and support your schools and affected pupils, make it a new year’s resolution to enrol on some training!

Internal alternative provision

Many of you will be aware of the importance of considering alternatives to suspension or exclusion Part 4 of the DfE’s Exclusion Guidance. These can include managed moves, offsite or alternative provision. Whilst not going into the details of these here an emerging school of thought is around providing internal alternative provision, particularly in secondary schools.

If you would like to understand a bit more about this the Education Endowment Foundation are undertaking a project looking into this in more detail: Education Endowment Foundation: Understanding the use of internal alternative provision for pupils at risk of persistent absence or exclusion

So, as we approach the end of 2024, we will no doubt hear a lot more about the above as the DfE works to deliver the new government’s education priorities. Hopefully we will see some positive outcomes and guidance emerging from the various reviews that have taken place over the recent period as well, we will try to cover all of these in future blogs.

As we move into the new year and the spring term, we need to remain focussed on our schools and pupils whilst being mindful of the many and ongoing changes and challenges that seem to be baked into our system of education.

At a recent governor conference, I was really struck by the words of our CEO Carole Bennett, when reflecting on her education journey and upbringing she suggested two things for governors to live by – if nothing else ‘be useful’ and ‘challenge your school leaders with positive intent’ – I think that’s a great summary of two key roles we play as governors!