History and geography are inextricably linked as subjects in their exploration of our planet, how we live and why we live the way we do. However, they are very different from a planning and teaching perspective, in terms of their national curriculum content and structure.

The national curriculum for primary history is clear on which aspects and time periods of the past we should focus on, particularly at key stage 2: A single bullet point such as ‘the Roman Empire and its impact on Britain’ can become the main content focus of a unit of learning.

Geography is organised differently. Let’s explore this further:

In geography, although the national curriculum sets out the broad content that we must teach at the respective key stages, the objectives are not neatly divided into year groups or topics, and the places to be studied are not specified beyond which continent. This leaves subject leaders and teachers to craft their own projects and units of work or to look to published schemes and materials to support them. This can be both liberating and confusing!

For example, one attainment target for ‘Locational knowledge’ in key stage 2 says:

- locate the world’s countries, using maps to focus on Europe (including the location of Russia) and North and South America, concentrating on their environmental regions, key physical and human characteristics, countries and major cities

This target is designed to be broken down, rather than taught as a single point. For example, a Year 3 or 4 unit might take a European focus, where a Year 5 or 6 unit might take a South American focus. These are school-level choices. Published schemes have often made these choices for us, but it is up to school leaders to reassure themselves that these choices are right for their setting.

With this level of choice in mind, where do we begin? How do we develop a scheme of work that:

… should inspire in pupils a curiosity and fascination about the world and its people that will remain with them for the rest of their lives.

National curriculum aims for geography

Another challenge is around how we create a curriculum that enables children to secure deep understanding and make progress as they move through the planned units? What connects the units of learning? What are pupils making progress with?

In order to ‘make progress’ it is likely that we will want to identify strands (concepts and threads) that repeat and deepen.

The final challenge is weaving in disciplinary learning - helping children to understand what it means to think and behave like a geographer, through meaningful experiences, that again build and progress over time.

With these elements in mind - the level of choice we have, and the need to have concepts/threads and disciplinary thinking which connect the learning across units, progressing and deepening over time - let’s consider how we might build and structure a curriculum, or simply interrogate and refine our existing geography curriculum.

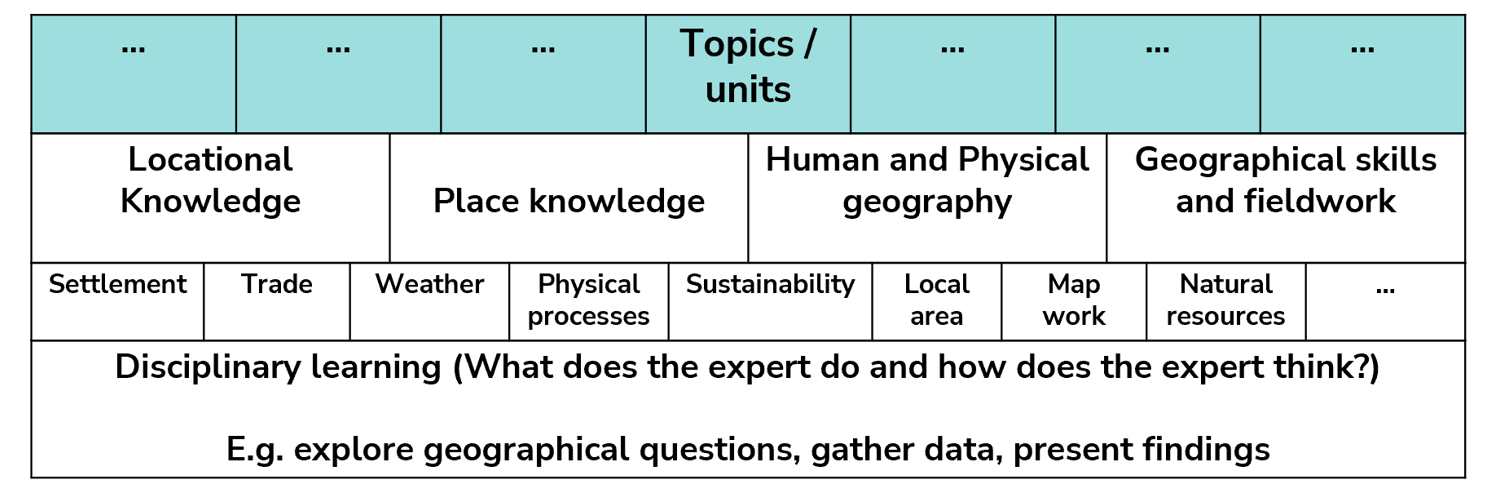

Let’s start by looking at the possible layers of learning that a geography curriculum could contain, presenting some of the above thinking in the form of a diagram.

Layers of learning in geography

In the diagram above, we can see the top layer of learning refers to the projects, topics or units of work. These are commonly found on a school’s long-term plan and are an overview of what the children will study in different year groups. Here, we may see topics such as, ‘Kenya,’ ‘rivers,’ ‘farming in the UK,’ ‘How is life in Mumbai different from life here?’ or ‘What is it like to live in the Amazon?’

The next layer down refers to what we will call the concepts of geography. There are four broad concepts identified in the geography national curriculum, used as headings for the attainment targets at both key stages 1 and 2: ‘locational knowledge’, ‘place knowledge’, ‘human and physical geography’ and ‘geographical skills and fieldwork’. These are identified in the national curriculum as components to be studied and are the pillars of geography. They are what make geography, geography. Each topic or unit will have aspects of these four broad concepts.

For example, if we were creating a topic for a KS2 class about the Amazon River, we would weave locational knowledge into the unit by using various types of maps to locate the continent, country then river. We would explore its relation to the other continents, countries and the equator etc. Depending on the age of the pupils, we may look at the lines of longitude and latitude the river falls on. We would employ our place knowledge by exploring what it is like to live near the Amazon River. How is the region similar and different to our home? What are the buildings like? Where are the major settlements? We might explore what jobs people have and what the people of the area produce and export. This would rely on our human geography. Using maps and computer-based mapping systems such as Google Earth, we may begin to predict weather, climate, and investigate what sort of vegetation may grow there. This would rely on our physical geography. We may investigate what sort of crops are grown near the river combining our human and physical geography. Depending on whether the substantive content had been taught in a previous unit, we may teach or retrieve information about how rivers are formed. Finally, to underpin all this research, we would be continuously employing geographical skills and fieldwork to collect, analyse, and present our data.

Why might we want to weave these four concepts together, as in the example above? If we look at the aims of the geography national curriculum below, we can see that it is important for children to develop contextual knowledge about the places they study. They do this by leaning on both human and physical geography and how they interact and affect each other. We cannot understand a place and what it might be like without looking at both aspects - human and physical geography. They are interdependent - one effects the other. The variations in climate, physical geography and natural resources across the globe have directly influenced human settlement patterns.

Therefore, to encourage a richer, deeper exploration of a place, we could combine sections of attainment targets to create a more well-rounded exploration of places.

Referring again to the layers diagram above, we will call the third layer (with ‘settlement’ and ‘trade’ named in the example), threads. These threads are chosen by the school and/or scheme and are woven through our geography curriculum, some appearing in more units than others. Children could make progress within these threads in a hierarchical manner (incrementally build their knowledge and understanding), as well as in a mastery approach (developing and building a stronger schema each time they meet a thread in a new context).

For example, a child may meet the idea of ‘settlement' in EYFS when they create small world towns and train tracks or when they take a walk around their local area noticing and naming features. In Year 1, they may delve further into a local area study and take a wider look at where they live, investigate any significant local features and notice and name the human and physical features. In Year 2, a child may encounter a settlement in a non-EU country and begin to compare it to their own locality. In LKS2, a child may encounter settlements when they study a region of an EU country and compare it with their own. And finally, in UKS2, a child may encounter settlement again when they look at a region in North or South America and possibly their own local area again through a different lens. These planned opportunities allow the idea of settlement to become a rich schema, seen from multiple views, multiple places and where possible, some places that are visited more than once through

Revisiting the same region or country in a curriculum is not necessarily to be avoided. In fact, it may be beneficial to explore fewer places in greater depth than many places at a superficial level. After all, we are aiming for rich schema development and trying to avoid creating a single lens view of a place.

It may be beneficial to explore fewer places in greater depth than many places at a superficial level. After all, we are aiming for rich schema development and trying to avoid creating a single lens view of a place.

An example could be a KS1 study of a Brazilian village and what it may be like to live there, investigating settlements, jobs and weather etc. Returning to the study of Brazil in LKS2, pupils might explore the Amazon River whilst learning about rivers. And finally, an UKS2 unit might investigate Brazilian land use, natural resources and a case study of coffee farming utilising knowledge of climate, vegetation belts, trade and fairtrade.

Indeed, this very point was made in Ofsted’s geography subject report: Getting our bearings.

Make sure that pupils learn about places in an appropriately nuanced and complex way. They should encounter the same places at different tims and in different contexts, or look at a place through a range of geographical lenses. Pupils should have some opportunities for regional as well as thematic studies.

Ofsted– Getting our bearings: Geography subject report Sept 2023

In each geography topic, unit or project, our planning and teaching should make clear links to other related learning, to deepen it and to build schema, to prevent learning sitting in isolation.

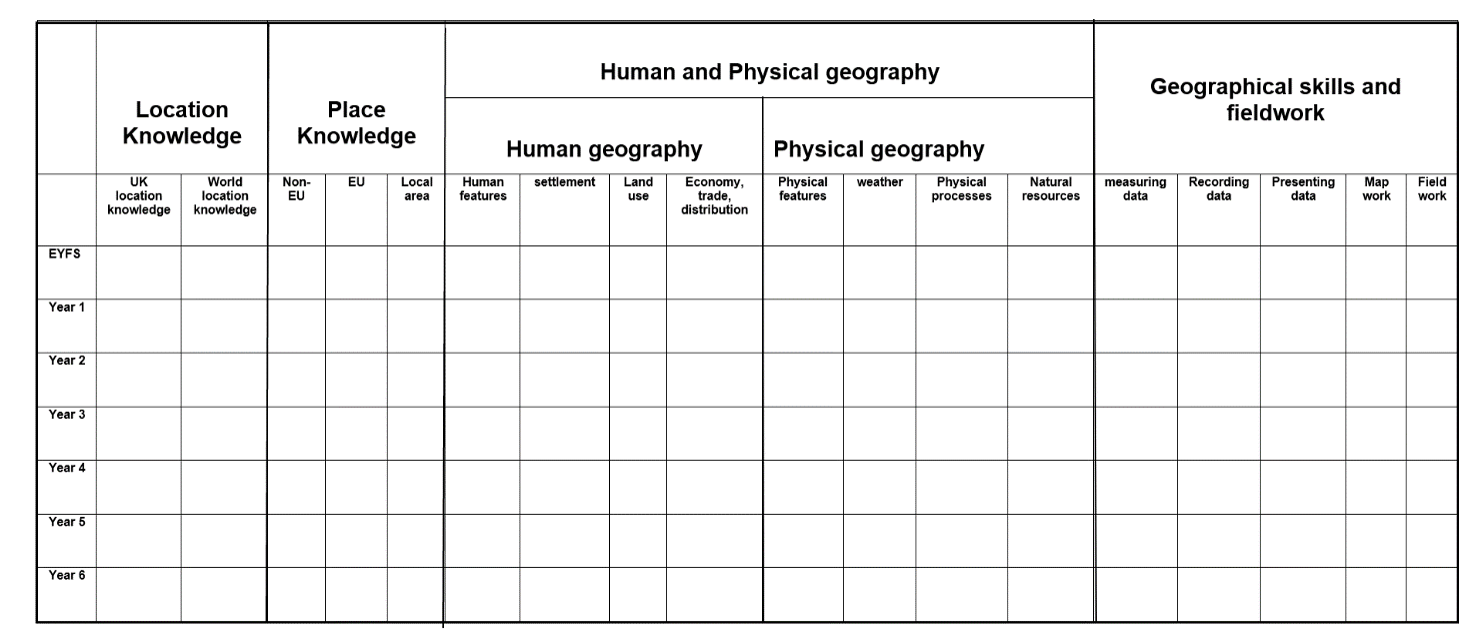

How might we track these concepts and threads through our curriculum so that our teachers and then children are aware of the prior learning? Possibly by using a progression document like the one above.

Geography progression map

Here, the four major concepts of geography are broken down into component threads. Tracking where these appear across the year groups and what learning objectives are encountered could be a valuable exercise for staff. This is not an exhaustive list, and schools may have other chosen threads they might wish to track.

When all staff can see where a concept or thread has been taught previously, they are enabled to make strong curriculum links, activating prior knowledge and thus creating a firm landing and sticking place for new learning. For example, drawing children’s attention to the fact that they worked with maps in their Year 2 project about Melbourne and made simple symbols for features of the area on a map will help reactive knowledge about symbols and keys. This will link with the new learning in Year 3 about particular OS symbols on a map of the local area. It will strengthen the schema around maps and symbols.

Drawing children’s attention to their learning about tectonic plates in the Year 4 Earthquake unit, for example, will reactive this learning and help the new Year 5 learning about mountains and volcanoes stick. Completing a retrieval activity about tectonic plates, what they are and what happens when there is friction, paves the way for learning about how mountains are formed.

This point was made as one of the recommendations in Ofsted’s geography subject report: Getting our bearings

Curriculum

Schools should:

Consider how pupils will build on knowledge, not only within a topic but over a series of topics, so that they can apply what they have learned in different scenarios.

Ofsted– Getting our bearings: Geography subject report Sept 2023

Making these explicit links between units of work is one way we can help children make progress in geography, developing their schema and strengthening learning. Linking the four major concepts of geography in each unit of work ensures that the teaching is deeper. It avoids the teaching of merely surface level detail and paves the way for a more analytical approach to understanding places, our world and how we affect things and are affected by them.

What if your school has bought a scheme of work? How might you utilise this approach if you are already using a scheme. Here, I will refer to Ofsted’s inspection handbook:-

Paragraph 241 states, ‘Inspectors will consider how well the curriculum developed or adopted by the school is taught and assessed in order to support pupils to build their knowledge and to apply that knowledge as skills.’

The important point here is the extent to which the scheme of work has been adapted to make sure that it is suitable for the particular school context. In adopting and/or adapting a scheme, a school will want to ensure that the content is well suited to its context. The school will also want to ensure that there are suitable threads and concepts that build over time, allowing pupils to build learning and make progress.

In summary, here are my top tips for developing a connected primary geography curriculum that enables progress and promotes depth in learning:

- Utilise learning from all four concepts of geography in each unit of work: ‘locational knowledge’, ‘place knowledge’, ‘human and physical geography’ and ‘geographical skills and fieldwork’.

- Contextualise human and physical geography by including it in the study of places: What are the human and physical features of this place? How do human and physical processes affect this place?

- Revisit places studied previously, with a different focus to avoid single lens viewpoints and to deepen learning.

- Think about creating a progression map so all staff can track and then support pupils to retrieve prior learning within the concepts and threads thus building rich schemas.

- Adapt your existing curriculum or scheme to make sure it is right for your school community, for example, in the places studied and the lenses used to study these places.