Differentiation in maths - scaffolding or metaphorical escalators!

Recently, I have been working a great deal with teachers on developing their skills at scaffolding learning rather than setting different levels of challenge (also referred to as ‘Tiered Learning’). Let me start by clarifying one thing. I am not opposed to presenting different levels of challenge. There are times when it is absolutely the most appropriate form of differentiation for the learners. For example, pupils who have significant gaps in learning or cognitive difficulties. However, it is the dominance of this approach within our primary maths classrooms that concerns me.

What is differentiation?

At its most simple level, differentiation is the teacher’s response to the variation amongst learners in a classroom. However, differentiation is a vast field, with multiple aspects and opportunities that need to be considered when deciding on the most appropriate adjustments to facilitate maximum learning. There is not a ‘one size fits all’ approach; nor is there a magic bullet. It relies on our professional knowledge of our pupils and consideration of a few key questions:

1) What is the long term learning outcome that is required?

2) What is the learning goal of the individual lesson?

3) How do we get our diverse classrooms to the desired outcomes? In essence, how do we go from Q1 to Q2 and back again?

Tiered Learning

This is the dominant form of differentiation that I encounter not only in classrooms, but also in published (hard copy or digital) resources. Fundamentally, teachers provide different tasks/activities to meet the needs of different learners. This approach has been used in UK classrooms for a number of years because it does have benefits. It allows pupils access to learning that they can (or should be able to) complete independently. In examples of best practice, this is a short term change in the learning goal to support pupils to acquire the knowledge, skill or experience to allow them to move to the next stage of learning. It is successful when a pupil has:

i) a cognitive difficultly and is working on a detailed personal curriculum that reflects their individual learning needs

ii) a significant gap in conceptual understanding that must be addressed to ensure that they are able to continue to develop their schema with clarity. A short term drop to accelerate rapidly back up to the levels of their peers.

I am not going to discuss those pupils with cognitive difficulties in this blog – it would be far too long. Please refer to our previous blogs here and here for focused conversation if you would like to explore this further.

I ran, and will continue to run, classrooms where self differentiation of tiered learning will be part of my teaching style. Warning: this form of differentiation needs very close monitoring.

Let us consider the ultimate outcomes if some of our pupils constantly access less complex or less challenging learning than their peers (either through teacher direction or self-differentiation). When do they get to reach the age-related expectations (ARE) pitch? If in Year 1 they are constantly exposed to learning experiences that are just below ARE, what happens to them in Year 2? Year 3? The gap continues to get bigger. Many Year 6 teachers feel the eventual outcomes of this – a pupil who was just off ARE in year 1 is now significantly off by Year 6. The pupil has missed many of the key learning experiences and their schema is fragmented, limiting their ability to translate learning across the curriculum. Used constantly and without consideration, children could be placed on metaphorical escalators that have different pre-set outcomes, and once you are on one it is incredibly difficult to jump to the escalator above as the gap increases throughout a school career.

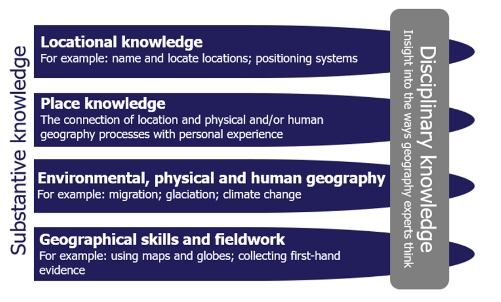

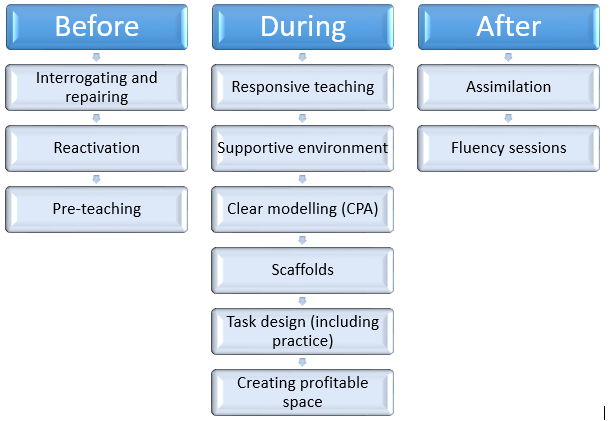

Figure 1: Some of the strategies which can be deployed to support learning

It can be successful though, if carefully managed through clear gap diagnosis, focused intervention, careful small step management, and most importantly, that those expectations are firmly attached to ‘getting back on track’. As such, tiered learning is both very time and energy demanding. I would always ask, is there another way to achieve the desired learning outcome?

Scaffolding

But what about these other ways? What else should be considered? This is where the list is almost endless. Figure 2 summarises the more common strategies that a teacher can deploy.

Do bear in mind that other forms of enabling access and tiered learning are not always mutually exclusive. They can have a symbiotic relationship.

For the purpose of this blog, I am going to focus upon scaffolding.

‘[a scaffold is] that [which] enables a child or novice to solve a task or achieve a goal that would be beyond his unassisted effort’ Wood et al 1976, p90

Scaffolding works in a similar way to its physical counterpart – it allows pupils who are ready to learn the concept but with certain barriers, access to learning that they would not be able, or willing, to reach without it. A key outcome of this approach is that they access the same thinking / learning experiences and continue to develop their understanding on a par with their peers.

When working with teachers, consideration of scaffolding opportunities has shifted their thinking about how to approach the needs of their learners. It makes classrooms more manageable, as through successful scaffolding we can all grapple with the same learning, collective power to conquer together. Then on to the next… together.

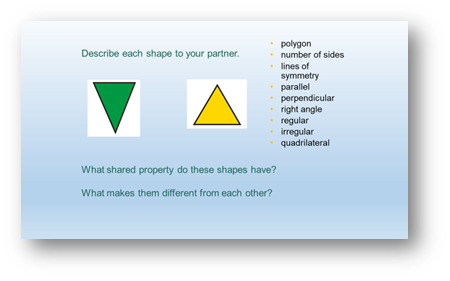

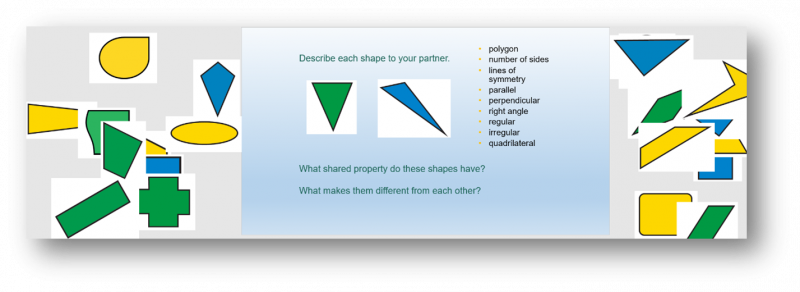

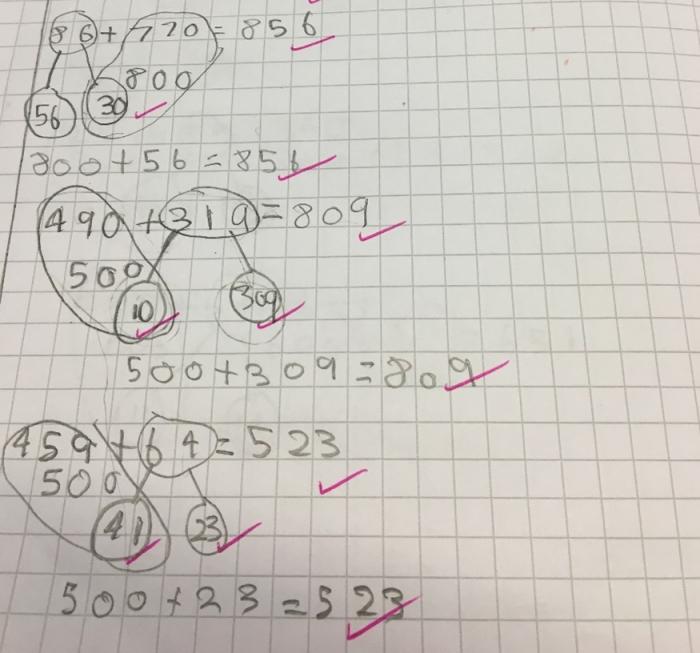

So what would this look like in the classroom?

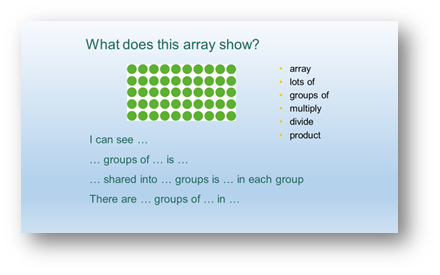

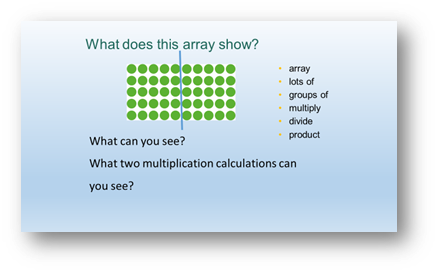

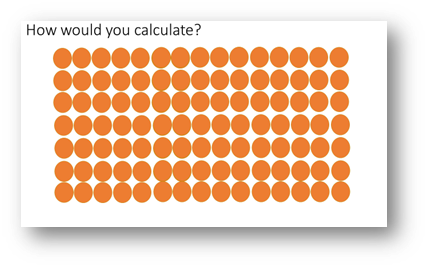

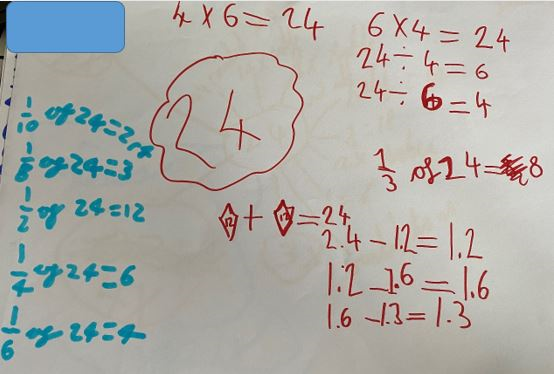

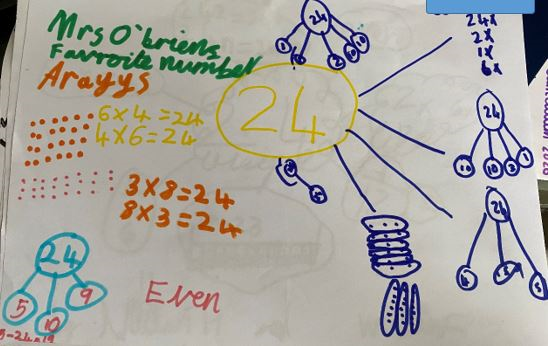

Beware of cognitive overload, try to keep it in mind. Stay focused on the key learning outcome, what exactly do you want them to learn in this sequence or step? For example, if the desired learning outcome is to be able to use the language of multiple and factor accurately, and pupils don’t know their multiplication facts, then providing them with a multiplication chart could be the scaffold (after making sure that they how to use it). If they don’t know their facts, this is going to be a barrier to understanding and accurately applying the language. By being given access to a simple chart, they can explore, secure and feel confident in the use of the key vocabulary language, and they will be able to apply it rapidly when they acquire more facts. The focus of the learning is not to be able to recall multiplication facts (that’s a different much longer journey).

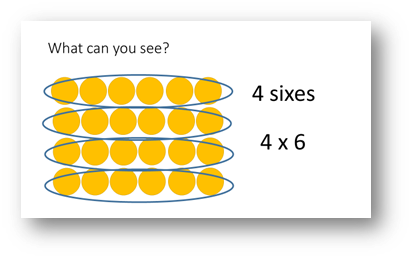

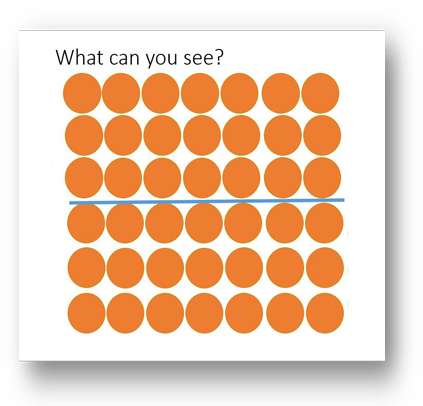

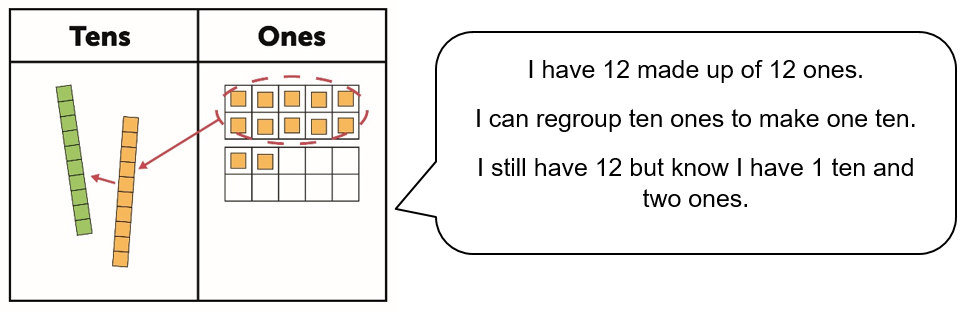

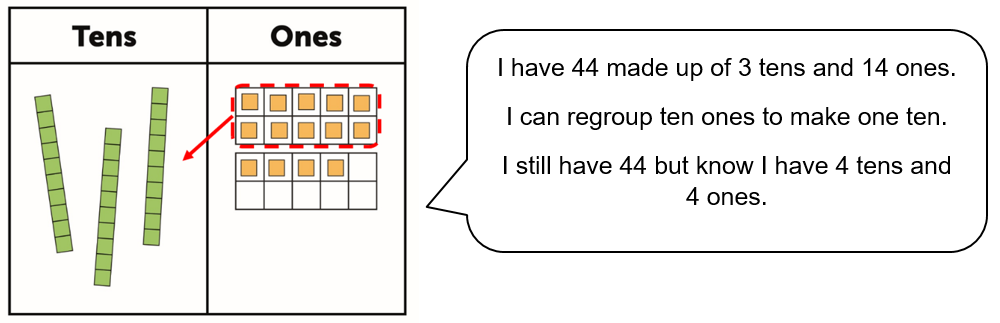

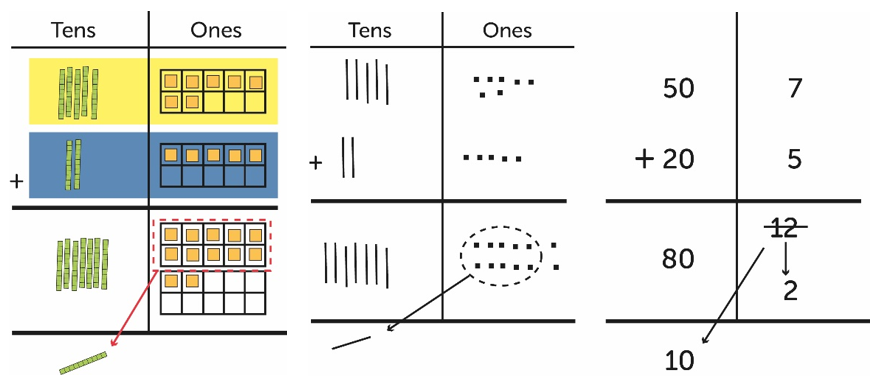

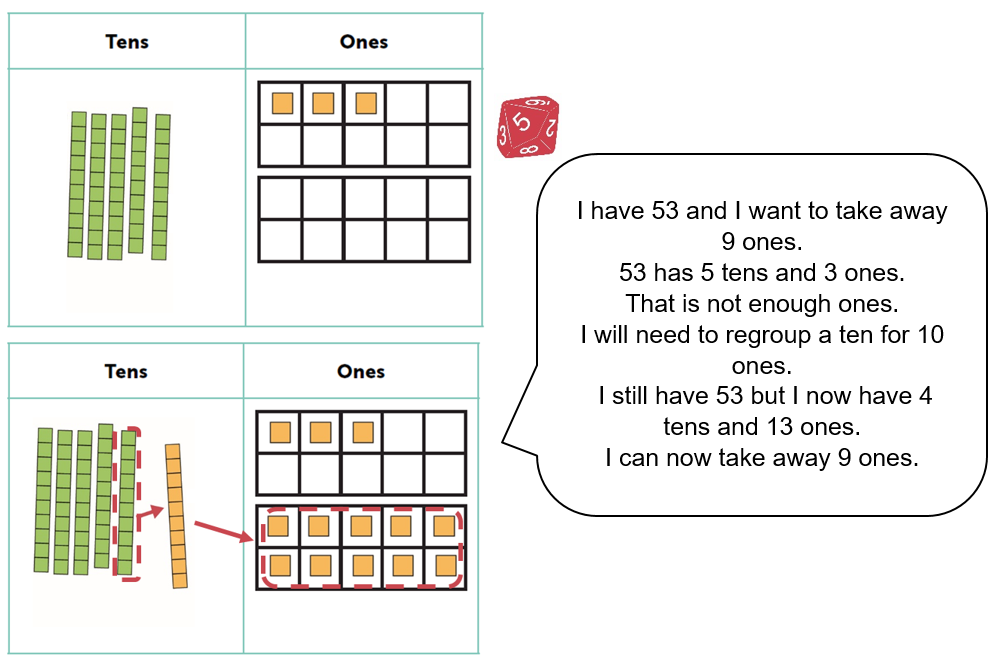

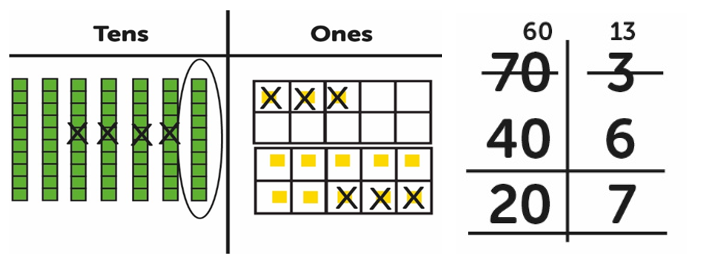

1) Are there any concrete manipulative or printed resources that would ease cognitive load? Do they have access to the same resources that were modelled? Pupils should have access to allow them to model out, explore and confirm for themselves as and when they need to. Some pupils may need a manipulative mat in order to contain/structure their resources – or they might get ‘lost in the sea of Dienes’.

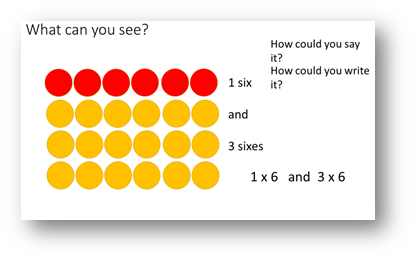

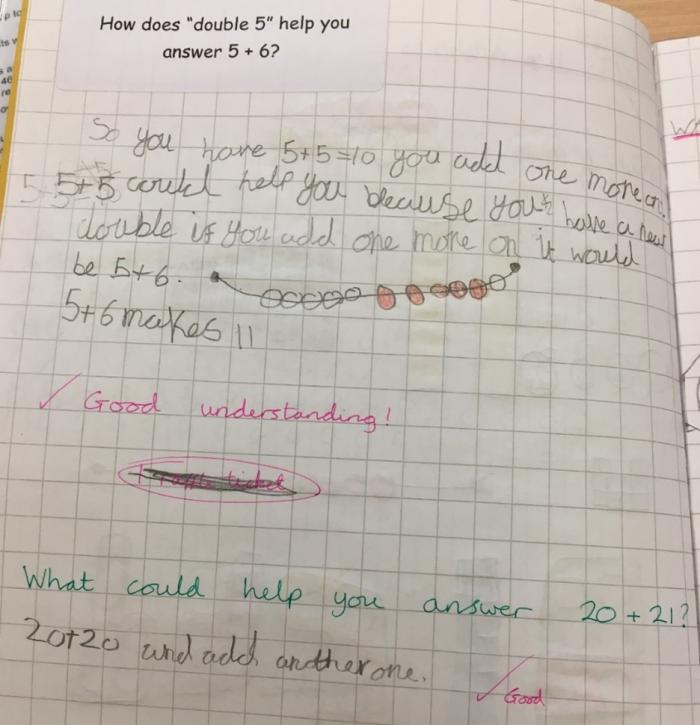

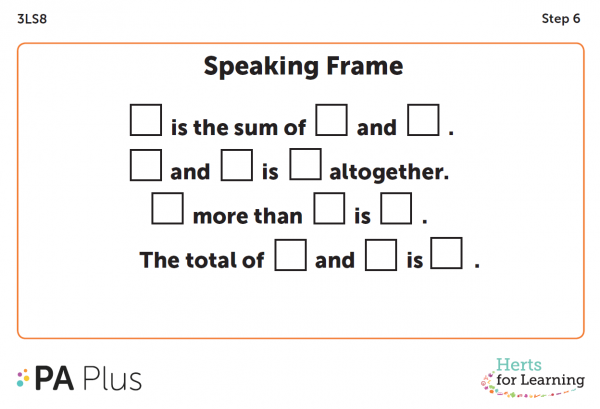

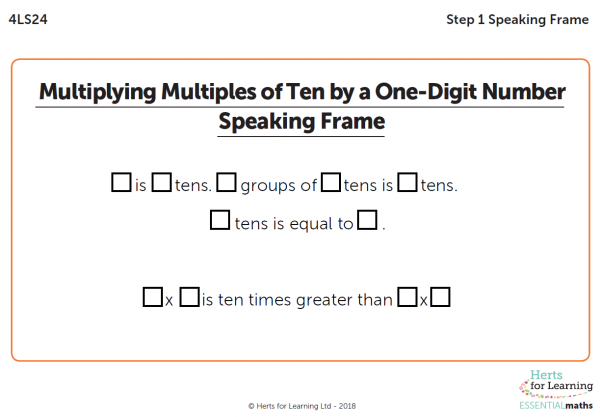

2) Speaking frames support pupils to structure responses in full sentences and in how to use new vocabulary appropriately. These have been a hugely successful part of ESSENTIAL maths, as the development of verbal reasoning is closely linked with the ability to construct personal schemas and knowledge into long term memory. In some cases, pupils are not able to track from the modelled speaking frame and need their own personal copy, so that they can track with their fingers etc.

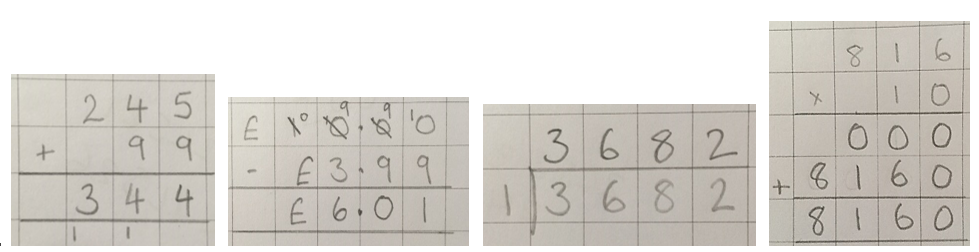

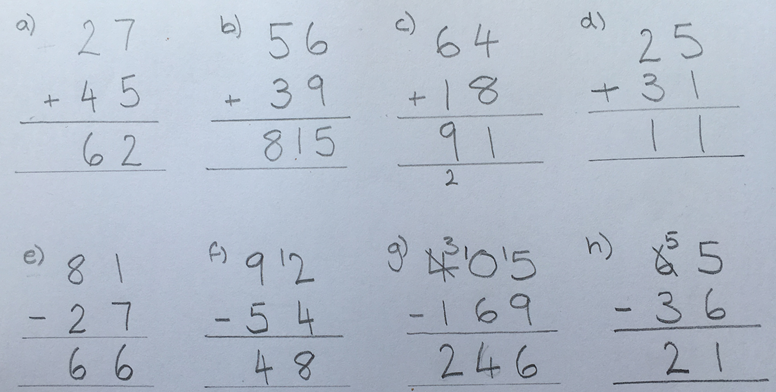

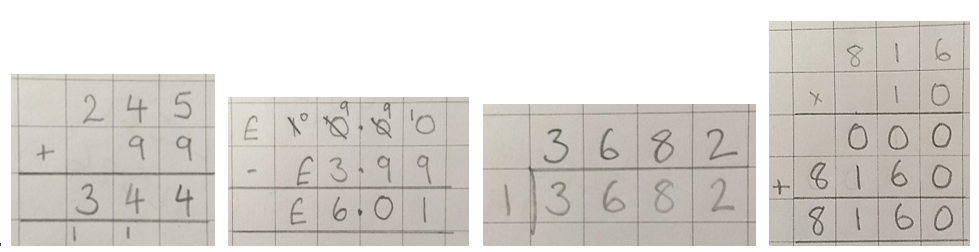

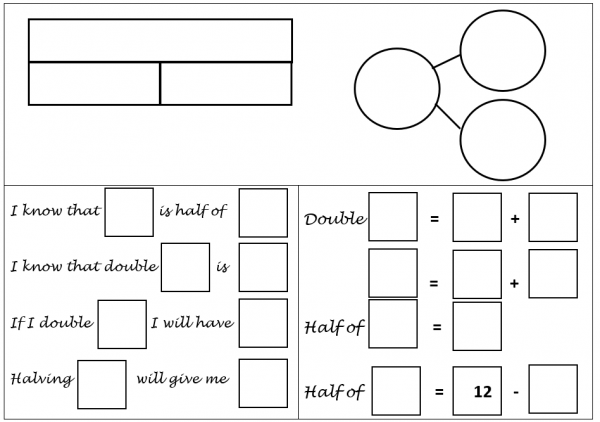

3) Recording frames work as organisers, supporting pupils to stay focused on key learning and enable some pupils to have more practice. Let’s take these two key functions separately.

4) Check-it stations support the development of independence and self-correction at the point of learning. It has been proven that to find and identify errors in your own learning is vastly more powerful than having them identified for you. Recently in a classroom, I asked one boy who had completed a set of calculations how he knew if he had them all correct. He shrugged his shoulders and said Mr X would mark his book. How much more powerful would it have been for that pupil to have checked some of his responses as he was working through them? Check-it stations can vary in content and level of support, but the default setting is simply just some of the answers. Then the responsibility lies with the pupil to identify where and what the error is and how the correct solution is reached. This prevents the proliferation of error within a lesson, has the added bonuses of more confident, self-checking pupils and frees the teacher to work with guided groups. Many schools who employ this now have editing pens at their check-it stations as well. A quick word from the experienced check-it station user – have at least 2 in your classroom to avoid the bun fight as everyone heads at the same time.

Staying focused on learning

A maths classroom is full of distractions. A recording frame can support a pupil in internalising a thought process, supporting development of efficient and clear recording, learning to contain their pictorial representations and symbols to ensure that they can follow their own chain of thought. They can also be adapted to enable greater depth.

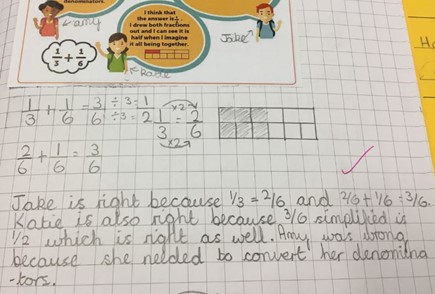

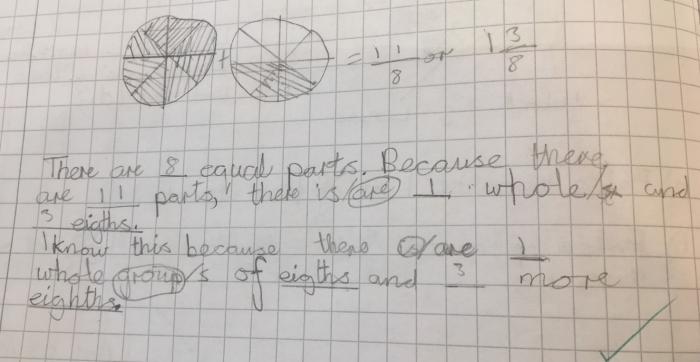

Figures 2 and 3 Examples of speaking frames from ESSENTIALmaths

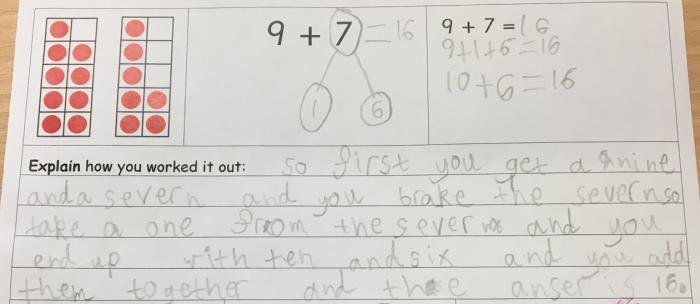

Figure 5 year 1 recording frame with challenge, ‘Can you complete the rest of the recording frame to make this true?’

Imagine you are a child who doesn’t write as quickly as your peers. Perhaps you get lost half way through a sentence as you are having to work harder on spelling and letter formation. You get through less practice. You might never get to the ‘tricky’ questions (this is why misconceptions must be exposed early in a practice sequence, but that’s for another time). What is the impact on your learning? Is this because you couldn’t ‘do the maths’? No, it is possibly because your fine motor skills aren’t as well developed as your peers or that your working memory is getting overloaded with other stuff. But you will eventually fall behind and the gap will grow – this isn’t fair. This is further explored in this blog here.

We need to get as many pupils as possible to become fluent and confident mathematicians. This is not for school league tables, this is because maths is a key life skill required to function successfully in our society. The longer children stay on parallel curriculums, through constant tiered learning, the harder it is to move them off. Are we content to have different expectations for pupils? Is it okay to leave children trapped on metaphorical learning escalators?

In this blog, I have only outlined a few of the different differentiation strategies that a teacher can deploy. If you would like to explore this further and gain a wider portfolio of strategies, please join us on our central training.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Child Psychiatry, 17, 89−100

Berk, L., & Winsler, A. (1995). Scaffolding children's learning: Vygotsky and early childhood learning. Washington, DC: National Association for Education of Young Children