There are pivotal conversations currently happening about how we enable and empower all young people to get the very best out of their education, with a focus on genuine equity: How we support all young people to develop positive self-identity, have broad horizons and experience success, through the curriculum we construct and education experiences we provide.

This could be our judicious choices of curriculum content; a manageable amount of well-chosen knowledge and skills that build (not over-cramming the curriculum), the careful mapping and sequencing of learning so that the accumulation of knowledge and skills closes gaps rather than allowing them to open, or using our curriculum to build a sense of identity for our young people (through the curation of what and who we study and why), helping pupils see themselves reflected. For each of these elements there is a growing awareness of the need to have this conversation openly – and for it to lead to action.

Our work on the curriculum is not finished; it is still evolving, and it is of great importance to all our young people that it does

This thinking permeates the work I do alongside schools – with leaders, class teachers and in the school community as a whole. We have a growing sense that there is a moral imperative within the curriculum we offer: To select judiciously and sequence carefully, so that the curriculum becomes a vehicle for promoting the success of all young people in their learning.

Making this really happen in schools relies on leaders (at all levels) feeling informed and empowered to make choices that they believe will build greater equity; within subjects, as well as across the curriculum and the learning environment as a whole.

In considering, researching and writing this article, I have been on an inspiring, but sometimes uncomfortable journey; exploring Emily Style’s article ‘Curriculum as Window and Mirror’, closely followed by the well-known ‘Windows, Mirrors and Sliding Glass Doors, by Rudine Sims Bishop, as well as blogs from Dr Dan Nicholls and the opening keynote from David Olusoga at The HFL Education Race Equity Conference: Time to Act (March 2023). More on each of these later. But suffice to say the reading and exploration of this area has motived me to want to take further action, and my aim is to further motivate schools in the same vein.

All four of the brilliant people mentioned above (and many others) have expressed the importance and power of the curriculum and in particular the content choices made, which shape our young people, how they view the world and their part in it:

Rudine Sims Bishop wrote ‘Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience.’

Similarly, Emily Styles referred to it as ‘the need for curriculum to function both as window and as mirror’.

Both writers use the analogy of a mirror to reflect, revealing the importance of our curriculum and content being chosen explicitly for this purpose of reflecting identity, as well as to act as a window to broaden horizons.

I wonder to what extent each school feels that their curriculum fulfils this vital role of acting in part as a mirror for their young people?

Our ‘windows and mirrors’ should be chosen to reflect and inspire – whether this is the artists and designers we choose as examples, the locations we explore in geography, the musical genres and musicians we encounter... The potential to craft bespoke ‘windows and mirrors’ individual to each school community is almost endless.

In David Olusoga’s keynote for HFL Education’s Race Equity Conference: Time to Act, he was clear that in his own school experiences he craved seeing his own identity within the history taught at school. He did not feel the teaching or curriculum he experienced held up a mirror in which he could see his own reflection in the content taught. He spoke about how our teaching of history needs to be more inclusive – sharing the real experiences of people, including where these are uncomfortable.

He also spoke about the danger of focusing on the ‘heroes’ of history – telling the stories in an overly positive and simplistic way, that cosmeticises history, rather than tackling some of the more challenging aspects within history. One example given by David was of teaching the industrial revolution, focusing on the textiles industry but without mentioning where the majority of the cotton came from; leaving out the enslaved people tasked with picking the cotton. This was an uncomfortable realisation for me – that I had also studied the industrial revolution at school, but don’t remember acknowledgement of the production of cotton by millions of enslaved people.

Our content choices should move beyond the ‘heroes’ of history, the standard artist selections or the cliché locations for geography. We need to be ambitious in the way we weave together content so that it (sensitively and appropriately) portrays the real challenges of the world we live in. In curating the content well, we offer a richer tapestry and we acknowledge imperfections for what they are, with a view to moving forward, with better intentions for the future.

In moving beyond the simplistic representations – the ‘usual’ selection of history, music, locations, literature or significant people – we also acknowledge that everyone should feel connected to our curriculum and that they play a significant part in what comes next – it could be them as the musician, artist, designer, scientist, architect or inventor we study in years to come.

Dr Dan Nicholls makes a further link to children experiencing disadvantaged and the sense of disconnect that can often go with this. In his recent blogs, exploring the reality for pupils experiencing disadvantage versus advantage and those who feel connected verses disconnected, he puts the point starkly:

‘As educators what we choose to include and how we sequence and curate the curriculum confers or denies power for our disadvantaged learners. Designing the curriculum as the golden ticket to the world for all children is a weighty ethical responsibility.’

Dr Dan Nicholls - Closing the disadvantage gap | Curriculum as the lever (February 2022)

‘The decisions we make about how we organise provision, have consequences for learners, that create or deny connection, systematically over time. We have come to accept the alternate realities, where those presently disadvantaged are disproportionately represented in the less connected, lower performing, under ambitious, alternate reality. They do not often feel the privilege of the high attaining reality.’

Dr Dan Nicholls - The disconnection of disadvantage | reconnecting the disconnected (March 2023)

There are several aspects now at play here: young people’s self-identity, their feelings of belonging and the position of advantage or disadvantage in which they currently find themselves.

This is certainly not to imply identity and advantage or disadvantage as being the same; they are not. But we need to accept that if a child does not feel connected to their curriculum, their school, their peers, then there is a disconnect. The disconnect maybe around self-identity and whether pupils see themselves as ‘belonging’.

It is this feeling of being disconnected that is potentially damaging to a young person’s education. We have a moral duty to ensure that the content of a curriculum and the way it is carefully sequenced and enacted impacts positively on all pupils’ sense of identity and belonging. In working through the carefully sequenced learning, both substantive and disciplinary, all pupils should feel empowered and experience success.

We need to acknowledge, however uncomfortable it may be, that having a curriculum which does not enable success, reflect identity, build belonging and broaden horizons is falling short - it is not yet doing its job, and so needs further work.

As Christine Counsell wrote in her blog ‘In search of senior curriculum leadership : Introduction – a dangerous absence’:

Curriculum is fundamental to schools. It is also fiendishly complex

Working on a curriculum is no small or easy task. Schools are not alone in navigating this; there is support available. HFL Education advocates the need for this continuing conversation and is keen to support schools. It may also be a case of small tweaks making a big difference, initially.

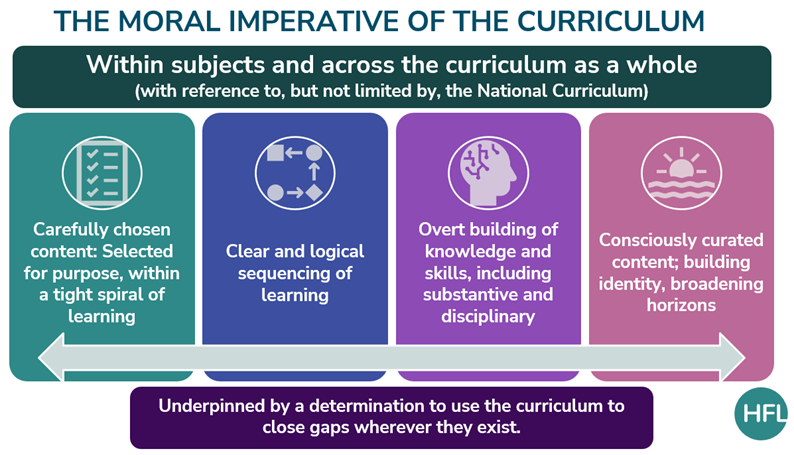

To navigate some of the complexity, this visual representation has been developed to help explore the various parts of this thinking. The moral imperative to continue to review and adjust the curriculum could be summarised as:

The purpose of the graphic is to break the thinking down into parts, so that each aspect can be explored, allowing us to focus on what matters, when it might otherwise feel like an overwhelming ask.

Alongside the graphic above, some points for schools and leaders to consider:

- how carefully and judiciously are content choices made? Who makes the choices? What has their lived experience been and therefore what biases might they have?

- do the content choices help to build identity and broaden horizons? Is it evolving into a curriculum of mirrors and windows?

- how clear are leaders about the knowledge and skills, both substantive and disciplinary, that pupils should learn? Ensuring that the amount is manageable with focus on the most important aspects.

- how logically sequenced is the learning, so that it builds gradually and cumulatively, allows the learning to be revisited, embedded and secured? Does it enable everyone to succeed, and how do you know?

If you’ve found this blog useful and would like support in any of these areas, please do contact us: kate.kellner-dilks@hfleducation.org

To keep up to date: Join our Primary Subject Leaders’ mailing list

To subscribe to our blogs: Get our blogs straight to your inbox

(If you are interested in blogs that relate to the content of this blog, select the equality and diversity and/or foundation subjects and curriculum design options from the list when subscribing).