Analysis of the papers can take many angles and I don’t hope to cover them all in this series of blogs; instead, I intend to use an analysis of the reading SATs to allow for insights into our current teaching practices in the hope of developing and sharpening classroom pedagogy.

If I miss anything of particular interest, please do get in touch, and I will try to explore that avenue.

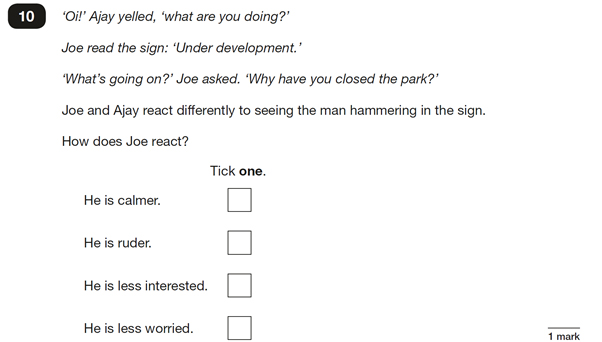

‘And, the award for trickiest question goes to…

Question 10!’

(Correct response rate = 53.9%)

To clarify, this question yielded the lowest national correct response figure out of all the questions relating to text 1 – The Park. In fact, only 4 questions relating to text 2 received a lower correct response percentage. Whatever way we look at it, we can safely say that many children found this one tricky.

According to the mark scheme, this question pertains to testing domain 2h (making comparisons within the text) – this was the only question relating to this testing domain. The challenge of this question relates to the subtlety in the author’s use of dialogue to indicate the characters reactions to the event. There are several clues within the text that would have allowed the children to note Ajay’s indignant response to finding the man hammering a sign onto the park gate: the most obvious is the use of the colloquialism ‘Oi!’ in Ajay’s opening remark. Most children will have been told off at some point or another for using this impolite method of gaining someone’s attention. This is closely followed by the verb ‘yelled’ in the dialogue tag. More subtle, but still accessible to most children, is the impertinent use of the direct question including the personal pronoun, ‘what are you doing?’ In contrast, in the wording surrounding Joe’s dialogue, the author uses the neutral verb ‘asked’ in the dialogue tag. Joe also begins his line of enquiry with a less direct question: ‘What’s going on?’ – omitting the personal pronoun ‘you’ that Ajay used in his question.

As a next step, the children had to work their way through the possible answers deciding what the cumulative information told them about Joe’s emotional response. I would argue that having read the text leading up to this scenario (if indeed they did! – see below for further exploration of this point), the children could have quickly eliminated the last two possibilities (he was neither less interested, nor less worried). I can see how some children would then have got in a muddle and ticked the second box, mistakenly offering a reflection on Ajay’s manner rather than Joe’s, but putting aside this potential confusion, I would have expected more children to have selected the correct response for this question.

This question provides us with an opportunity to reflect on our teaching practices and to consider if we are doing all we can to support children in paying attention to the subtle spells used by authors to craft their writing.

Essentially, this question invites the children to reflect on the author’s skill of character development through dialogue. This skill should not be new to the children. In fact, they should be adept at using this skill themselves in their own writing, as according to the Y6 writing Teacher Assessment Framework a pupil working at the expected standard can:

- integrate dialogue in narratives to convey character and advance the action

(NB. I have added the bold for emphasis)

I would argue that if children have successfully managed to master this skill in their own writing, then they should be able to spot it in a text with ease. We do know however, that the use of effective dialogue in writing can be a potential pitfall for young writers who are attempting to reach EXS (see HfL blog: ‘Write Away’ and other lessons derived from the KS2 writing moderations, plus associated links within the blog). Following the 2018 moderation visits, our Herts moderators noted that beyond issues associated with poor punctuation, some children struggled to make the dialogue within their narrative writing effective – it often failed to give the reader an insight into the character’s feelings or motives. From my experience, I can say that for the most part, the dialogue that I encounter in pupil’s writing more frequently performs the function of ‘advancing the action’ rather than ‘conveying character’. If, on reflection, you conclude that your teaching of writing has focused more on the use of dialogue to advance action rather than convey character, then this might explain why your children struggled to get under the skin of question 10.

In order to rectify this situation, you may need to reflect with care upon the texts that you choose to share with your pupils. It could be argued that there has been a noticeable shift in recent years towards the use of books for class study that prioritise action over character development. I recently stumbled upon a debate on Twitter arguing for and against the use of Kensuke’s Kingdom as a class text. Whereas in the not-too-distant past, this text was a stalwart of the Y6 reading spine, many people involved in the conversation felt that the book was too slow, or boring; some went as far as saying that nothing happened in it. In terms of epic gun battles, car chases and fantastical beasts, the book is somewhat lacking, but many in the same conversation argued that the magic of this book comes not from the fast-paced action, but from the slow and careful revelation of character across the story.

Therefore, by reflecting on our book choices and ensuring that we select texts that have plot and action as their central themes, alongside texts that prioritise character development, we may find that our children recognise the role that dialogue can play in achieving both with greater ease.

Don’t forget the performance!

Readers familiar with Herts for Learning will know of the KS2 Reading Fluency Project. The principle underpinning this project is that we gain a better understanding of the texts that we read if we read them in the way that they are meant to be read. By that, I mean by scooping adjacent words and phrases together to create cohesive chunks of meaning, adding the correct intonation, inserting the correct audible micro pauses and using the correct emphasis, all of which allow the message of the text to become clear to the reader. Pupils who have taken part in the project will be familiar with the term ‘performance read’. This is a term that we ask teachers to use regularly with the children throughout the project so that it begins to signify a type of reading that goes beyond simple functionality, and that moves them away from a monotonous and robotic form of reading that may have become the norm for some children. When a child gives a ‘performance read’, they read the text like they mean it, and as the author intended it to be read – this is achieved through intensive modelling of prosodic reading of a range of challenging texts. Towards the end of the project period, we ask teachers to support their pupils to develop a silent ‘performance read’ voice, which only the child will hear in their head. I would argue that a child who is experienced in the fluency project strategies, and who has been regularly directed by their teacher to do their ‘performance reading’ (even – and perhaps especially - in the context of the SATs test) then a child should be able to hear that Ajar is indignant and angry, whilst Joe is calmer and more considered.

My assumption is that many children – in the heat of the moment, or due to a lack of prompting by the teacher to read the text aloud in their head using their ‘performance reading voice’ – didn’t utilise this strategy. This is a shame as our project has shown the power of this approach, especially for less confident readers.

Non-fiction needs fluency too

I would go on to argue that even fewer children would have brought their ‘performance reading voice’ to the table when tackling the non-fiction text that followed ‘The Park’ extract. Recently, we have been studying video footage of project pupils reading both fiction and non-fiction pieces and we can see that children are more likely to use their ‘performance read voice’ when tackling fiction, rather than when tackling non-fiction. Seeing as the Bumblebee text held the second position within the test paper, it was always going to be more challenging; combine this with the fact that many children may not have thought to use the skill of performance reading to help them gain a clear understanding of this text, we can see why some children may have found it a challenge.

Going forwards, teachers may choose to reflect on the priority they place on non-fiction reading in their classrooms. Specifically, how often to pupils hear the teacher modelling expert prosody when reading aloud a non-fiction piece? Do teachers – like many children – reserve their ‘performance reading voice’ for fiction, as opposed to non-fiction texts? These questions are worth exploring if your pupils appeared to struggle with text 2.

Embrace Disorder!

The English Reading Test Framework document provides the following statement under the ‘Breadth and Emphasis’ section, p.11:

The questions are placed in order of difficulty, where possible, while maintaining chronology with the text.

This tells us that we can expect the questions to align to the texts in a sequential manner, with each question requiring information from progressive sections of the text. I know that some teachers have translated this statement into test guidance for their pupils, suggesting that they mark a line after they have found information that answers a question, assuming that they will not have to read back before that line to answer any subsequent questions.

In reality though, the tests do not adhere strictly to this guidance. To exemplify this point, we can turn to the questions pertaining to the second text in the 2019 test, ‘Fact Sheet: About Bumblebees’. The set consisted of 14 questions. These were indeed sequential until the final 4 questions (from question 24 onwards). Each of these final questions required the pupil to take a jaunt back through the text, sometimes going as far back as paragraph 1. Seeing as question 23 asked children to focus on the sub-section entitled ‘Energy drink for bees’, if the children had been geared up to expect a strict adherence to the sequential questioning guidance, then many would have been left trying to tease out answers to the last 4 questions from the small sub-section entitled ‘Act now’ – an impossible task!

The answer to this predicament is to ensure that pupils recognise the importance of reading the whole text, and most importantly, getting a feel for the structure and key themes/messages of the entire piece before embarking on the questions. Furthermore, if they are taught to summarise as they read – perhaps circling some key words, or providing a make-shift sub-heading in the absence of any provided by the author – then you would hope that they would have a pretty solid overview of the piece before beginning to track down answers to specific questions. This overview would hopefully trigger directional pointers to the child when faced with a question that appears to not stick to the chronological rule.

I hope that this blog provides enough to get teachers thinking about some of the ways in which they might interpret the findings of this year’s reading SATs paper outcomes, and how their findings might be translated into effective classroom pedagogy.

For more insights into the effectiveness of the HFL Reading Fluency Project,