- Do we need to teach MRS GREN?

- Do pupils really need to memorise kingdom, order, phylum…?

- Do I need to teach the rock cycle?

- Do pupils need to use the terms igneous, metamorphic and sedimentary?

Are you relieved to find out that the answer to all these questions is, no?

Throughout my ten years of supporting schools to reflect on and develop their primary science curriculums, I have had countless discussions about content that was being taught but was not actually in the primary science curriculum.

It is not uncommon for schools to be teaching content that goes beyond the primary science national curriculum requirements, without realising it. This could be because the national curriculum requirements are not well understood. Sometimes it is because a scheme or resource has gone beyond the requirements and subject leaders and teachers are not aware of this.

In The 10 key issues with children’s learning in primary science in England report published in 2021, one of the issues identified was that children’s learning in science can be superficial and lack depth. An observation made in relation to this was that sometimes there was an ‘overload of inappropriately selected science.’ This was described as when, ‘Planning fails to consider the national curriculum requirements relevant to the age group resulting in teaching including content that is beyond the expectations.’

Ofsted also mentioned this in its Finding the Optimum report:

‘In a few schools, pupils were being expected to learn content that was too technical. This was because they had not secured prerequisite knowledge first. For example, Year 6 pupils in one school were learning about genetics without having learned relevant prior knowledge. This was not surprising, given that in the national curriculum genetics is not introduced until the secondary phase.’

There are many potential consequences of teaching content that goes beyond the national curriculum requirements including:

- Misconceptions -Teaching some content too early can lead to superficial understanding or the creation of misconceptions. For example, respiration is sometimes discussed as being similar to breathing which is a misconception that can be hard to correct and is best avoided.

- Less time available - Teaching additional content will mean there is less curriculum time available to secure the fundamental knowledge and understanding. This includes the disciplinary knowledge needed to understand and work scientifically and the time to practise working scientifically skills.

- Too technical - Content which is covered within the KS3 and KS4 programmes of study, may be too technical, or pupils may not have the required prerequisite knowledge to understand it. This may result in pupils not understanding and reaching the conclusion that they are not very good at science and switch them off to science learning.

The aim of any school should be to have an ambitious science curriculum that supports all pupils to understand the world around them. New learning should be connected to pupils’ experiences and prior learning to help them build rich and detailed schema. Jumping ahead in content can result in possible connections being missed.

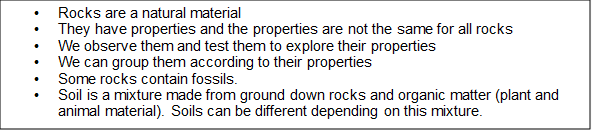

Content that is sometimes taught in ‘rocks and soil’ in year 3 demonstrates this well. Although the topic title, ‘rocks and soil’, only appears once in the primary national curriculum it is part of learning about materials and should be connected to what pupils have previously learnt in KS1 about materials. This can be done by focusing on the content in the box below:

Pupils can be supported to learn this content through a range of practical experiences that will develop both this substantive knowledge and also their working scientifically skills. This might include observing and testing rocks, observing uses of rocks (for example in buildings and graveyards) exploring how they have changed over time, researching fossils and exploring and investigating soil. (All of this is suggested in the notes and guidance section of the national curriculum for this topic).

Unfortunately, what sometimes happens when pupils learn about rocks in Y3, is they miss the learning described above and are instead taught about the rock cycle and expected to learn and use terms such as sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic, which is the content outlined in the KS3 programme of study. By jumping straight ahead to this content, the opportunity to ground, connect and link new learning to what pupils already know may be missed. Some teachers also find that teaching the KS3 content has to be more teacher led and provides less opportunity for the practical work that develops working scientifically skills as well as substantive knowledge.

‘But what about challenge?’

One potential argument for the inclusion of additional content is that it has been included to challenge pupils. However, there is plenty of opportunity to challenge pupils’ thinking and get them to think deeply while focusing on content that is in the primary national curriculum.

For example, when comparing living and non-living things we can spend time correcting the misconception that plants do not move. This can be done through time lapse videos on Explorify or on the BBC Green Planet and through looking at examples pupils can see such as daisies and dandelions closing overnight or when it is very overcast. We can also introduce questions such as: ‘Is a seed alive?’ This aims to provoke thought, discussion and encourage children to justify their ideas.

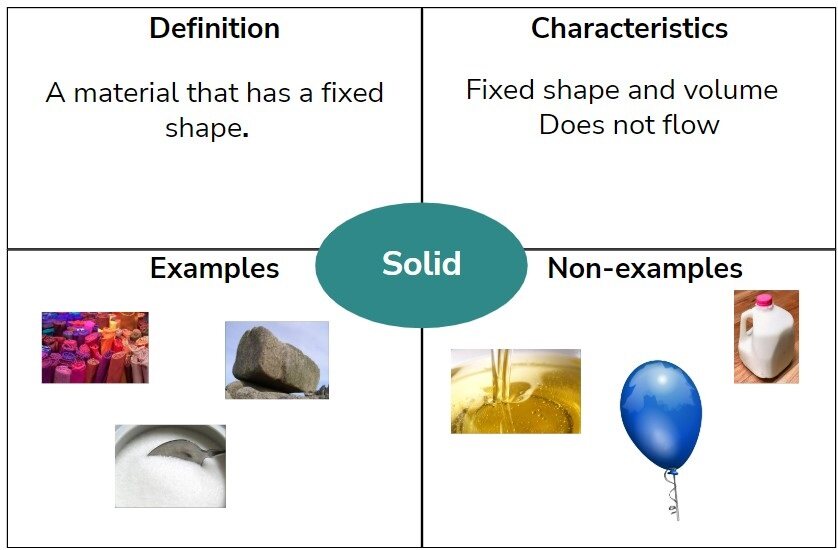

Another good example comes from the ‘states of matter’ topic in Y4. We can challenge pupils to really think about the properties of solids, liquids and gases by looking at a range of examples. Through using many examples of new vocabulary or a concept, more is learnt about the concept being studied as different examples will allow different aspects to be made clear. In the Frayer model image below three examples of solids are given. The rock displays many of the properties pupils typically think about when thinking of a solid it is rigid and hard. However, the fabric is flexible, can change shape, and can possibly be torn which are not properties typically associated with a solid. Granular solids, like sugar, are interesting examples to discuss as they take the shape of the container and can be poured. This is because they are a collection of grains which are solid. Pupils can be guided to look at grains individually to realise individually they do have properties of a solid. Pupils could also explore interesting mixtures of solids, liquids and gases such as shaving foam, toothpaste or my favourite: cornflour gloop sometimes referred to as ‘Oobleck’ which acts like a solid when under stress but will flow like a liquid at other times. These examples will challenge pupils’ thinking and preconceptions and ensure they have stronger understanding of the properties of solids, liquids and gases which is a great foundation for the next stage of learning in this area.

We could also challenge pupils by giving more time for pupils to take greater responsibility in planning, doing and reviewing enquiries which support their understanding of substantive knowledge but focus on developing the full range of challenging working scientifically skills. This is particularly relevant in UKS2 which lists a range of working scientifically skills that are not easy.

For example, in year 6, rather than spending lots of time trying to memorise Carl Linnaeus’s classification system (including kingdom, phylum, class…), pupils could plan their own enquiry to investigate variables that affect the volume of gas produced by yeast when learning about microorganisms.

Including additional content

There may be occasions where a school chooses to include content that goes beyond what is outlined in the national curriculum and extend learning for good reasons, such as it reflects their school community or pupils have asked questions that the teachers decide to answer.

For example, one school I worked with decided to spend more time in KS1 ‘materials’ discussing the impact of plastics, particularly plastics in the ocean, as they had recently switched to using pasta straws in the school canteen and the children were curious about why this decision had been made.

Another school explored sensory impairment when learning about senses in KS1 as they had members of the school community with sensory impairment.

Extending learning through additional content, should only be done if it can be explained at an age-appropriate level and pupils are secure with the fundamental learning outlined in the national curriculum and have had opportunity for reinforcement and practice of this.

Where can you go to for support in reviewing choice of content in your science curriculum?

We have created a document (understanding the national curriculum requirements for primary science) listing some of the most common content that is taught but is not in the primary curriculum. The aim of this document is to develop understanding of content in the national curriculum and facilitate discussion about what is in a school’s curriculum to support leaders and teachers to make conscious choices about what they choose to teach and why. If your school subscribes to Primary PA plus, then this document is free to download when you are logged into the HFL website. If you are not yet subscribed to PA Plus, then the same document can be accessed for a small charge on our HFL shop.

For further support on reviewing content in your science curriculum, the first stop is to go back to the national curriculum paying particular attention to the notes and guidance section. PLAN assessment also has free knowledge matrices which outline key learning in each topic alongside prior and future learning. If you are interested in a wider debate about the purpose and content of a primary science curriculum you may also be interested in Primary Curriculum Advisory Group.

We also offer bespoke in school science support to help evaluate, develop and implement a science curriculum that is logically sequenced to enable all pupils to gain a strong foundation. If you would like to discuss this, please do get in touch: charlotte.jackson@hfleducation.org.