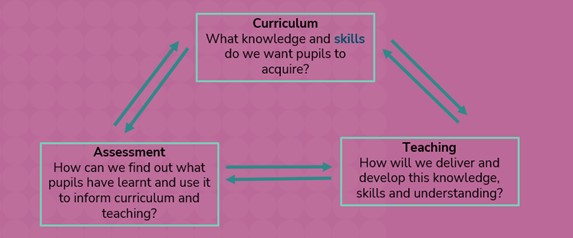

Let’s be honest, assessment itself doesn’t simply begin with assessment. In fact, if we want to assess effectively, we need to first be thinking about our curriculum as a whole. What knowledge and skills do we want our young scientists to acquire? And then, how do we deliver this to ensure we are developing the knowledge, skills and understanding we intend to? Next, does the task we ask the children to complete show the knowledge and skills we intended for them to learn? Finally, does the work they provide show us that they have met the requirements for that particular lesson?

So where do we need to begin?

Ultimately, the ‘intention’ of learning is the key – what is the focus of the lesson? You may call this a WALT, an LO, an LI, an ‘I can’, but at the end of the day it is what we want the children to learn.

So, what could be the focus of a science lesson (particularly if you are completing a practical task)? It may be:

- developing understanding of the scientific approach to enquiry;

- developing knowledge and understanding of the natural world (substantive knowledge);

- learning how to use a piece of equipment or follow a practical procedure; and/or

- quite possibly a combination of some of the above.

And then, within that, which particular skill/what particular knowledge is the focus?

Armed with a clear objective and adding some success criteria, that shows how the children can achieve the learning you laid out, the purpose of the learning becomes crystal clear (Sarah Earle, Assessment in the Primary Classroom).

However, we all know that this is easier said than done…

How do we word it?

In fact, building learning objectives is, arguably, the most important part of planning and delivering a lesson. Should they be long and explanatory? Should they be short and to the point (especially if you are expecting the children to record it themselves)? Should they use technical vocabulary or aim to be more in child-speak? As Shirley Clark points out, the crucial part of any learning objective is that every child understands the intention of the lesson – whether they’ve written it themselves or not is not what matters.

Ultimately, the technical language we would ask the children to use in a science lesson should definitely be used in the learning objective (particularly if it is a specific skill or a new concept, we wish for them to learn/use).

Secondly, it should be context-free which allows children to understand that the skills or knowledge they are gaining aren’t tied specifically to that context but can be used in many different ways and returned to on a regular basis (Sarah Earle, Assessment in the Primary Classroom). We often do this particularly well in English where the focus of the learning intention is generally linked to the convention or genre as opposed to the specific context or text that is being used as the vehicle.

Within science, this is also possible by thinking about our learning intentions as skills or concept-specific as opposed to context-specific. This then leads teachers to know exactly what they expect to see when they assess the children against the substantive or disciplinary knowledge; it invites the teachers and children to answer the question: How well have I achieved this outcome? The success criteria can almost be used as a checklist to see how well the objective has been met.

Example

The below example shows how to build this kind of objective within a pattern seeking activity and shows explicitly the difference between a context-specific and concept-specific intention:

| Context-specific | Skills/concept specific |

|---|---|

| How can I find a pattern between the size of a person’s handspan and the number of sweeties they can collect? | How can I find a pattern in the data? |

|

Success criteria:

|

Success criteria:

|

It is very clear how this skill/new understanding can actually be applied to many different contexts and can be a talking point to show the children that we could actually use this exact objective and criteria in a different context.

When children focus their recording on the learning objectives they cut down the time spent writing just for writing’s sake (recording what they’ve done) and they have more time to think, discuss and record what they’ve actually learned (Thinking doing, talking science).

This precision and the outcomes we see will allow us to be confident that pupils have acquired the necessary knowledge and skills rather than just experienced them.

So, let’s spend more time making our learning intentions purposeful for our outcomes and assessments of the skills and knowledge the children have acquired work to inform the next cycle of our teaching and learning.

To receive more information like this and to be informed of the release of part 2 and 3, please subscribe to receive our subject leader updates.

Voices from the Classroom

Our new blog series, Voices from the Classroom, allows primary science teachers to share particularly effective practical experiences they have had with their classes. It’s a great way to showcase what your school is doing and written guidance and examples are available for those of you wishing to participate.

If this is something you would be interested in participating in, please e-mail Charlotte Jackson charlotte.jackson@hfleducation.org