When the Teacher Assessment Framework (TAF) for writing was released in 2015 (then updated in 2018), there was almost a collective gasp from teachers across the country regarding the apparently heavy grammar weighting. ‘Why has composition and effect disappeared? What about authorial intent? What does it mean to exercise an assured and conscious control over levels of formality.’ Grammar needn’t be controversial, as it is implicit in spoken and written communication and quite simply makes meaning of words.

I wonder whether we may simply need to re-frame our thinking around the teaching of grammar. Our chosen approach can provide a ‘tool’ for the writing job at hand. What if we avoid the ‘tick-box’ approach which oftens sees grammar taught discretely and aims to provide evidence of grammar objectives? By teaching children how to use grammar for effect within their writing – carefully considering its impact on the intended audience – we may just see those desired skills of composition and effect come through. What if we focus our teaching time on developing children as authors? It is almost akin to the chicken and egg analogy. What comes first in creating a successful piece of writing and consequently a successful writer – grammar or composition? It is true that one relies heavily on the other.

What does the key stage 2 teacher assessment framework (TAF) tell us?

Let’s take a closer look at those meatier key stage 2 TAF statements which do not appear to explicitly reference grammar:

Working at the expected standard

The pupil can…

- write effectively for a range of purposes and audiences, selecting language that shows good awareness of the reader (e.g. the use of the first person in a diary; direct address in instructions and persuasive writing)

- in narratives, describe settings, characters and atmosphere

- integrate dialogue in narratives to convey character and advance the action

All three of these statements necessitate an understanding of how to use grammar in writing. For example, if pupils are being taught how to write a diary, they need to understand how to manipulate language for informality. As such, they would benefit from learning how to make use of the (always joyous to teach) apostrophe for contraction. In contrast, if children are learning to write a newspaper article, they will need an understanding of more formal aspects of language such as the passive voice, as well as direct and reported speech, impersonal tone and so on. Children will only be able to describe settings, characters and atmosphere if they understand how to successfully use noun and prepositional phrases to give detail, and how the manipulation of clause structure can help develop mood.

Focus on ‘the why’

Let’s take the fronted adverbial which takes pride of place in year 4. I would hedge my bets that many children would be able to explain the function of this piece of grammar quite confidently:

‘It tells us where, when or how…’

I wonder, however, if we posed this question to the children: ‘So why do authors choose to use them?’ whether they could answer so confidently? We must consider that if children are not taught how to apply grammar through their writing - the effect the device creates and, consequently, how the grammar choice affects the experience of the reader - they cannot truly understand its purpose.

Connect reading and writing

“Every hour spent reading is an hour spent learning to write; this continues to be true throughout a writer’s life.” – Robert Macfarlane.

How can grammar be taught through writing, for children to better understand its purpose and effect? Quite simply - by reading. If we provide children with high quality models for writing, from high quality texts, they will be able to see how authors manipulate and utilise grammar for effect. What better way for children to develop as writers, than to explore how other writers use grammar to convey a message to the reader?

Let’s delve into the opening page of The Children of the King by Sonya Harnett.

“She heard it: footsteps in the dark.”

Consider the rich conversations that could be had with children concerning the use of grammar in this opening line alone. The use of the short, one clause sentence immediately hooks in the reader with a feeling of impending threat. We could explore the use of the colon to join the two ideas together and to introduce the ‘it’ that she was hearing with a dramatic pause, maintaining the brevity of the sentence. We could delve into the use of the prepositional phrase ‘in the dark’ which instantly helps to create an image in the reader’s mind.

“Cecily Lockwood, aged recently twelve, quailed in the darkness beneath her bed and listened to the steps getting closer.”

In this second sentence, we see the use of an embedded clause giving us additional information about our female protagonist – key to introducing the character. The use of a multi-clause sentence creates a contrast from the previous single clause sentence, ensuring cohesion for the reader but continuing to develop that feeling of suspense in the setting. These are both examples of how the effective use of grammar can build mood and atmosphere at the start of a story leading to… don’t worry, no spoilers here!

This is not just the case in key stage 2. The national curriculum programmes of study for years 1 and 2 focus on the building blocks for writing: securing sentence structure, embellishing this with the introduction of coordinating, and some subordinating, conjunctions for pupils to communicate their intended message to the reader. If we are to nurture aspiring authors at the earliest point in their schooling, pupils need to understand how to purposefully communicate that message, by noting how successful writers use sentences for effect.

The opening two sentences from The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson demonstrate both single and multi-clause examples for pupils to consider.

“A mouse took a stroll through the deep dark wood. A fox saw the mouse and the mouse looked good.”

Imagine the rich discussion that could be had with the children about why the author may have chosen to start with this simple sentence: perhaps to create the setting for the reader to visualise. Why might the author have used the coordinating conjunction ‘and’ in the second sentence to link two ideas? Perhaps so that the reader understands the relationship between and fox and the mouse. Do you notice how the author has repeated ‘the mouse’ for emphasis across the two clauses? Have you spotted how the noun ‘wood’ has been expanded to help the reader visualise? Normalising the discussion of grammar as part of the writing process across all primary classrooms is essential so children are consistently taught how their writerly choices impact their writerly goals. Yes, read it first and enjoy the writing as a reader, then dive back in to consider it as a writer.

Going for greater depth

If we consider our high attaining writers, or those walking that greater depth line, their choice of grammar (and its impact on the reader) is the driver to securing this standard. There is no coincidence that the opening statement of the key stage 2 greater depth standard states:

“Pupils can write effectively for a range of purposes and audiences, selecting the appropriate form and drawing independently on what they have read as models for their own writing (e.g. literary language, characterisation, structure)”

‘Drawing independently on what they have read’ is at the forefront. If children receive a diet of connected reading and writing teaching, which explores a range of grammatical techniques, they can innovate on these examples, making choices, so their writing is geared towards their audience and purpose - their writing goal.

What does the research tell us?

Through their 14 key principles, The Writing For Pleasure Centre, highlights the significance of reading when nurturing aspiring writers. The principles outline the importance of connecting reading and writing and allowing children to think of themselves as writers. Reading aloud others’ work can increase engagement as well as having an impact on increasing the range of grammatical features used in their writing.

Professor Debra Myhill, Director of the Centre for Research in Writing at University of Exeter, has undertaken extensive research on this topic. She states that “Using authentic texts... shows developing writers how different grammatical choices change how their writing communicates to a reader. We see this as a way to empower young writers and help them understand the power of choice.” Her LEAD principles offer a useful structure for the teaching of ‘Grammar as Choice’ and the University of Exeter website offers up plenty of resources to exemplify the approach.

A grammar toolkit

Children could consider grammar as a toolbox of cumulatively acquired skills allowing them to select the most appropriate skill to communicate their intended message. Using metacognitive talk with children when we are modelling writing is a great way to teach children about how they have the authorial choice when it comes to utilising grammar:

‘I have used a single clause sentence here, but an embedded clause could add some crucial information for my reader…’

When grammar is woven into the writing process, we can support children in understanding how its effective use can communicate the author’s meaning and purpose to the reader.

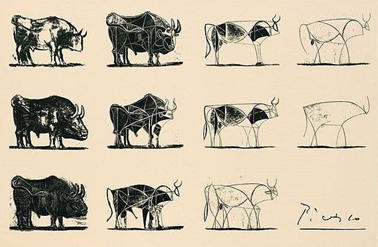

A final thought with thanks to Pablo Picasso.

If we teach children to learn the rules of grammar, with a view to their impact on the reader, only then can they learn to bend and break them. We may associate Picasso with the ‘simple’ line drawings on the right of this image. Indeed, all of these images were created by Picasso. He learned all the skills necessary for accuracy within his compositions and then chose those he wanted to use to best suit the purpose and intended effect. I would argue that writing is no different – that is how we can create a new generation of authors.

References:

Literacy for pleasure: reading and writing connecting – The Writing For Pleasure Centre (writing4pleasure.com)

Read, share, think and talk about writing – The Writing For Pleasure Centre (writing4pleasure.com)

Resources for Teachers | Writing resources for teachers | University of Exeter

Grammar for Writing? An investigation into the effect of Contextualised Grammar Teaching on Student Writing. Jones, S.M., Myhill, D.A. and Bailey, T.C. (2013), Reading and Writing 26 (8) 1241-1263