When the new National Curriculum was first published a few years ago, I used to talk about the three ‘C’s’ of curriculum design with mathematics leaders. These being cohesion, coverage and consistency.

Cohesion referred to the design of the curriculum. The National Curriculum document simply presents a series of statements in domain content order for each year group. Leaders had to decide how best to connect this learning in a way that ensured the mathematics in the classroom flowed from lesson to lesson and helped pupils see the interconnectedness of concepts. Think, for a moment, about pupils you know who do not really have a sound understanding of proportionality. I wonder if this is a result of how they have experienced fractions. As part of the number system, as quantities and in the context of shapes – but separately. Developing cohesion is somewhat trickier than deciding which bits of learning need to be apportioned to which terms and weeks.

Leaders also had to ensure there was coverage. By this, I do not mean that pupils had to simply ‘experience’ all of the curriculum statements and deep learning would follow. More specifically, pupils experienced the breadth of learning required to help build their schema. The skilful curriculum design provided sufficient opportunities to revisit and deepen understanding.

And what about the three aims of the curriculum? Don’t forget fluency, reasoning and problem-solving. Not as bolts-ons but manifested in the way that the curriculum is delivered.

With regards to consistency, I meant maintaining an unwavering focus upon ensuring high quality teaching in all classrooms. Simple to say – much trickier to do!

Inherent in all of this was the pressure upon leaders to ensure that colleagues had sufficient subject knowledge and teaching expertise. By subject knowledge, I am referring to the expertise teachers need to have about the conceptual development in maths. And how this informs the selection of effective teaching approaches for a concept. This being across the phases teachers work in and not just the year group they currently teach. This is challenging in one subject let alone across all of the others that make up a primary school’s curriculum!

The challenge of this for leaders is the reason, I assume, most have reached out for support. By support, I mean resources.

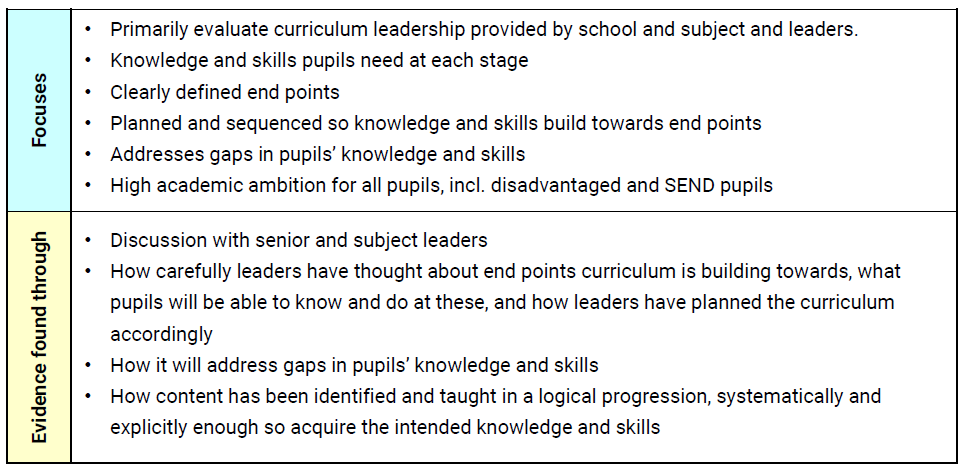

Only a few years have passed and it would appear that another important organisation has become very interested in curriculum design as part of their quality of education judgement[1]. I would accept that my original three ‘C’s’ were very broad. They were presented as useful hooks for thinking. I am now happy to accept OFSTED’s three I’s: Intent, Implementation and Impact as the new lens and language that all leaders use.

It is not my intention with the rest of this blog to offer a critique. Let’s not start about how often I have heard that this is the year of reading – that’s perhaps for another time! Instead, I wish to use this as an opportunity to re-explore curriculum design for mathematics and offer some points of reflection and support. I think these new lenses are helpful. I also wish to consider sources of evidence that might be used in an inspection. This isn’t offered as a checklist to help leaders feel they have all bases covered if visitors arrive. Instead, as points of note to consider the reliability and accuracy of our own evaluation.

It was, and still remains, our key intention to help leaders ‘take control of their curriculum’. The National Curriculum is a broad framework. It needs to be adapted and made right for each school’s context. So what does that mean?

The inspection framework offer an insight.

“Inspectors will take a rounded view of the quality of education that a school provides to all its pupils, including the most disadvantaged pupils (see definition in paragraph 86), the most able pupils and pupils with SEND. Inspectors will consider the school’s curriculum, which is the substance of what is taught with a specific plan of what pupils need to know in total and in each subject.”

(paragraph 167)

Now to Oftsed’s three eyes, I mean I’s.

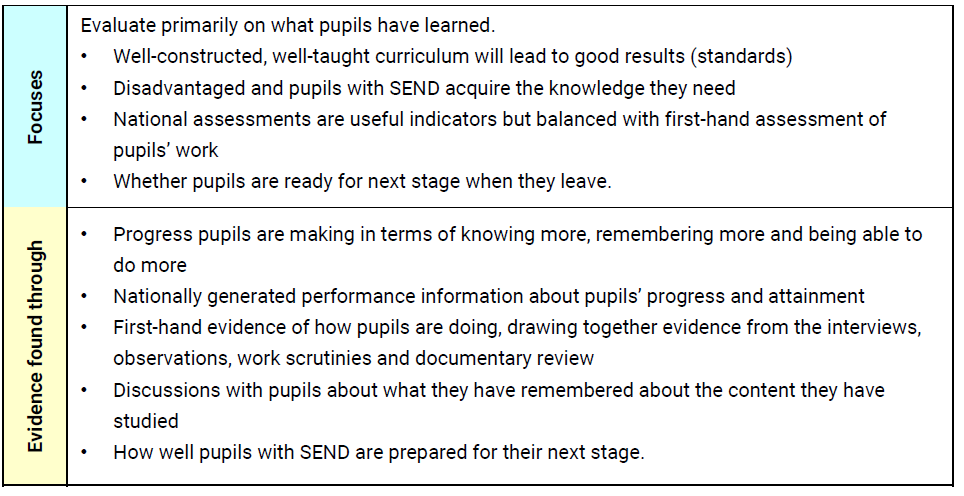

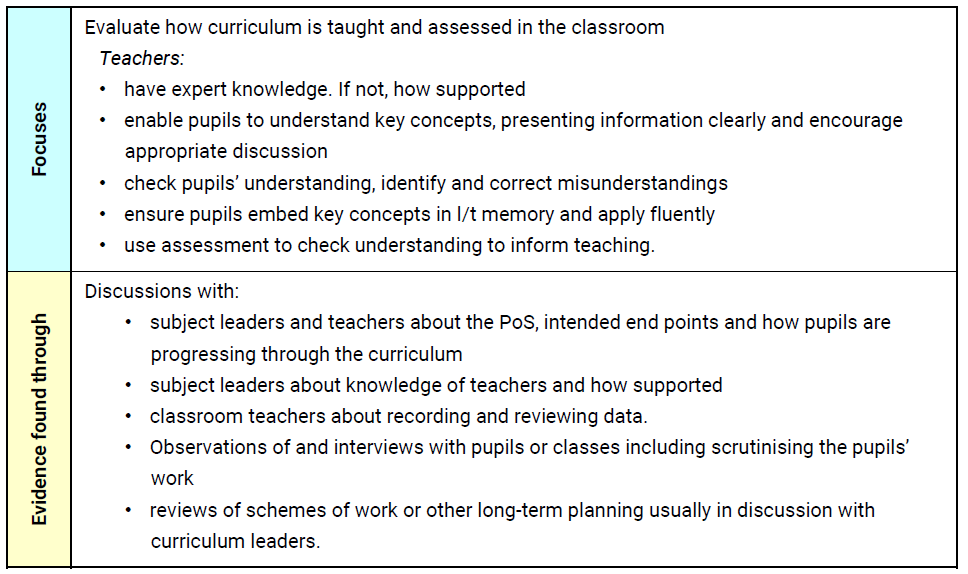

Intent is defined as the way a school’s curriculum sets out the knowledge and skills that pupils will gain at each stage. In essence, the curriculum plan. Implementation refers to the way in which it is taught and assessed. In Ofsted’s words, “to build their knowledge and to apply that knowledge as skills”. I often describe this as the way in which the planned curriculum manifests itself in the classroom. Finally to impact. This is the outcomes pupils achieve as a result. It is important not to lose sight of this aspect as I have frequently and incorrectly heard leaders suggest that Ofsted are no longer interested in outcomes. Secure and deep learning is the reward for a rich maths curriculum, well planned and expertly executed. Whether that manifests itself in test outcomes is a slightly different point.

The handbook outlines a number of points that are worthy of further consideration. So let me take each of these in turn and offer some thoughts.

I referenced ‘cohesion’ earlier. In many respects, this is equivalent to intent. As such, it is reflected in the careful planning of the curriculum. The way that the knowledge and skills are identified and sequenced. Both in terms of conceptual development across the primary phase but also the conceptual development within a year group. It is seen in the clear end points that this is building to. For most schools, the national curriculum steer this.

The bullet point I am interested to ponder on in paragraph 170 is this one.

“The curriculum reflects the school’s local context by addressing typical gaps in pupils’ knowledge and skills”

I agree. The school’s context in this sense is about what your learners are like. Patterns in weaker areas of mathematical understanding and mathematical behaviour that inform curriculum design. So pause for a few moments and consider these questions.

Are there any areas of learning in your mathematicians that are not as strong as you would like?

Is this common across the school or isolated to classes or groups?

As a result of this what adjustments are needed to your curriculum?

Your response maybe to focus upon increasing time for certain key learning focuses. Sharpening fluency. Some schools have identified key skills in each year group. This is a useful step. What is required here though is to ensure that these are secured. Of course, these skills may change over time as learners will be different. Identifying and prioritising certain areas of learning is very helpful but the ensuring that pupils actually do secure these is the most important aspect. Clear intent. It is skilful implementation that leads to impact. Read more about this in Siobhan King’s excellent blog Detecting shaky learning and dealing with it .

The handbook suggests that the main source of evidence for this is discussion with senior and subject leaders. It is essential that you own your school’s mathematics curriculum. Most schools make use of resources to support this. It is crucial that leaders know how the resources supports them. That it was selected and adapted because it provided the key focuses that teachers and learners need. Does it help with the sequence and flow of learning? Does it support the effective use of representations that secure deeper conceptual understanding? Often referred to as ‘Concrete Pictorial Abstract (CPA)’. Does it support the use of the correct mathematical conceptual language and the language to work on the mathematics?

I move now to explore implementation. As I have previously stated, I think about this as the ‘reality in the classroom’. When you are next describing what you think is happening in each of your mathematics classrooms, pause and consider what your thoughts would be if this was the reply. “Let’s go and see this in action.” In some ways, this is the thread of the ‘deep dive’ approach to evaluation in the inspection framework. As leaders, it is fundamental that we have an evidenced view of the reality. Hoping that your colleagues are is not the same as knowing they are. This isn’t about engaging in increased monitoring exercises. Talk to any of the maths team and they will tell you that ‘weighing the pig doesn’t make it any fatter!’ This is related to how leaders actually lead on professional development in mathematics. How they improve teaching. And the final part of any improvement (or enhancement) cycle – knowing it is working as you want it to.

This is the essence of the bullet point that references teacher’s ‘expert knowledge’. I would suggest that this is the perennial challenge and core motivation for leaders. It may seem obvious but is nonetheless worth stating. With strong knowledge of conceptual development and a repertoire of effective teaching strategies, practitioners are then more likely to teach more effectively. Ensuring that learning is secured for all because they are very acutely aware of what misconceptions pupils face and so can teach to expose and address them. They are secure in what to look and listen for and so are the masters of assessment.

I have the frequent pleasure of supporting teachers so an example may help. It is from a Year 1 classroom a few weeks ago. The lesson focused upon developing pupils’ use of the 0, 5 and 10 benchmarks. A crucial skill that takes time to develop in Year 1. Pupils were using a demarcated number line to place various single digit numbers. The aim here was for pupils to use the 0, 5 and 10 as anchor points to help position other numbers. Indeed, the pupils were able to place 6 quickly using the 5 benchmark. They also had ’0-20 beadstrings’. I asked many pupils to show me ‘6’. In each case, pupils counted the beads individually. They were still counting and so hadn’t secured the notion of helpful benchmarks in numbers. Not once did any pupil slide the 5 red beads and then 1 further white bead. You might say that this is where the teacher was going next.

As leaders, it is crucial to not be too presumptuous. In our roles as leaders and supporters of teachers we need to ask. I did. It was clear that the teacher hadn’t noticed. And as we explored the journey to date in year 1, it was also evident that many of the earlier key learning points were not quite secure either. The teacher, by their own admission, was not that clear about these essential components. So we unpicked this in a bit more detail and identified precisely what learning needed to be revisited and secured. Importantly, also identified what this would look like when it was happening.

I do not offer this vignette as criticism of teachers at all. I have a very privileged position in working with and supporting lots of teachers to develop their practice. More crucially, I offer this as an example of what leaders need to do. The teacher had planning support resources but needed to spend a bit more guidance to unpick the conceptual learning underpinning this sequence of learning.

I had a recent conversation with an Ofsted inspector and we talked about the need for leaders to ‘look at’ and not ‘look for’ in classrooms. It may be pedantic but the former provides the leader with a position of inquisitiveness. To look carefully and consider what the information is really revealing. Further questions really help. In the example above, the discussions with pupils in lessons really helped understand what they hadn’t quite developed yet. From moments like this, the skilful leader is able to identify the support and guidance that will have the greatest impact.

In the handbook, there is reference to the transfer of knowledge to the long-term memory. I am not quite sure of my own understanding of this neuroscience and so are more enamoured with the phrase “new knowledge and skills build on what has been taught before and pupils can...” use these in a range of contexts with fluency (that last bit is my addition). This relates again to the design of the curriculum. Its flow and connectedness that supports teachers to manage the learning journeys for pupils. I am looking forward to returning to work with the Year 1 teacher in a few weeks.

As with intent, the handbook identifies a range of sources of evidence. These are well known. Discussions with leaders about the programme of study and how pupils are progressing through it; observations of learning in classrooms; pupils’ ‘work’; and discussions with pupils. Of note and I applaud it is the reference to the support for teachers. I refer to this as the professional development of teachers. I regularly talk about this essential ingredient with leaders. It can take a myriad of forms but is the only catalyst for even greater practice.

The framework also identifies how this can be evidenced through conversations with teachers. I note this last point as I rarely hear leaders talk about this and it can be a really rich source of feedback.

Impact, in the handbook, is aligned to “what pupils have learned”. This is hard to disagree with. Positive learning outcomes should and will be the result of a rich maths curriculum, which is well constructed and taught. National assessments are useful indicators but not necessarily the only measure. A view of what is happening in classrooms, in books, through interviews will add to that picture.

Aligned with the earlier point about ‘local context’ to address gaps in learning, there is reference to the learning success of disadvantaged pupils and pupils with SEND. In many senses, this will be the ultimate litmus test of your curriculum intent and implementation. The extent to which your curriculum design and delivery supports the success of your most vulnerable learners. By vulnerable learners, I do not necessarily preclude this to the ‘defined’ groups. I simply state that any pupil who is in danger of not securing the learning is vulnerable.

To support subject leaders, I have generated a short set of questions. These are not intended to be exhaustive or used as a definitive script. Instead, they are offered as further prompts for reflection and evaluation. They have been created from many conversations with school leaders and listening keenly to those involved in school inspections or curriculum evaluation.

Subject leaders

How do you decide what to teach in each year group? Why this? Why now?

How do you support the development of subject expertise?

With regards to the sequence ... what learning is next? ... what came before?

What is your approach to revisiting key learning?

How do you check pupils are making progress through the curriculum?

How well do pupils secure key learning?

How are your pedagogical approaches matched to the learning taking place?

What’s the reality in the classroom? Let’s see that in action.

Teachers

Why did you teach that...? Where is the learning heading? What came before? How has this shaped your decisions?

Why have you decided to teach it like that?

How did the lesson content and activities ensure the learning was secured?

How are you supported to develop your understanding of the key components pupils need to learn?

How are you supported to develop the best ways to teach these?

What has been the impact of that?

I believe that the three lenses offered to us by Ofsted are useful. I would, however, urge readers to return to the crux. This is not about the need now to write out a lengthy statement for three I’s. A quick reflection to ascertain salient points would be helpful. Not swathes of time dedicated to create a set of rhetorical soundbytes. The quality of your mathematics curriculum and how well it is served up in classrooms is what you need to invest energies into. This will be evident in what you say about how you have designed it for your school, but ultimately about what happens in classrooms and the secure learning pupils build as a direct result.

References

Handbook for inspecting schools in England under section 5 of the Education Act 2005, The Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted), May 2019