A current DfE initiative is encouraging more schools to facilitate more flexible working for teachers to aid recruitment and retention. The DfE are interested in understanding perceptions of flexible practices such as job sharing and part-time working, and hearing more about barriers (actual or perceived).

There are definitely perceived difficulties involved in constructing a secondary school timetable with a number of part time staff, as well as real challenges. The challenge is to encourage more headteachers to feel that flexible working works well in their schools

As an experienced timetabler. I know that incorporating all the requests of part time teachers can be a challenge. Many timetablers that I help perceive that part-time teachers will give them less flexibility in an already complex situation. I always use the analogy of a jigsaw, that you always start with the edge pieces of the puzzle and part-time teachers are some of those edge pieces.

I often encounter two extremes of thought: the first is that we must do everything possible to accommodate the wishes of the part-time teachers, sometimes to the detriment of other staff and students; the other is that if they want to work in the school then they will accept the timetable they are given. I think the best route, as always, lies somewhere in between these two.

The most important factor is that there must be clear communication and planning when there are part-time teachers involved in a school timetable. For example, if sixth form lessons must happen at particular times due to consortium arrangements, then leaders need to consider the needs of the part-time ‘A-level’ teachers when deciding on the structure of the curriculum. Similarly a part-time teacher may need to be given the choice between teaching A Level and taking their non-working day on a particular day, based on the structure of the A level curriculum. All of this needs to be clearly explained to all parties in good time in order that a solution that suits all parties can be found. In addition, there needs to be a consideration of the impact on full-time staff. If, for example, all the part-time teachers do not work on a Friday, almost all the full time teachers will be teaching a full timetable on that day so there is very little flexibility and potential compromise to the quality of the timetable. It is important that these sort of issues are resolved as early in the timetable planning process as possible to ensure that any arrangements that the part time teacher may need to organise, such as childcare, can be facilitated.

Both school leaders and part-time teachers need to be clear and candid about where there is room for flexibility, and where there are reasons why school leaders would like the part-time teacher to work at a particular time and/or why part-time teachers would like a particular day or time of day as non-working.

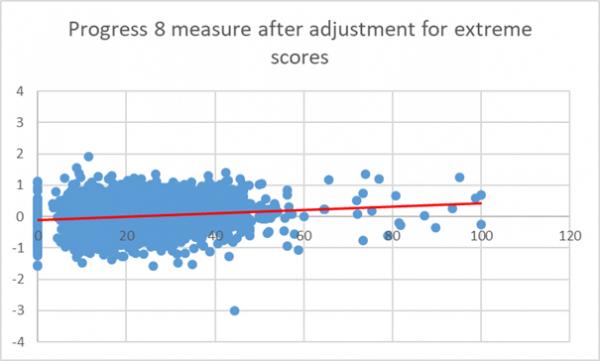

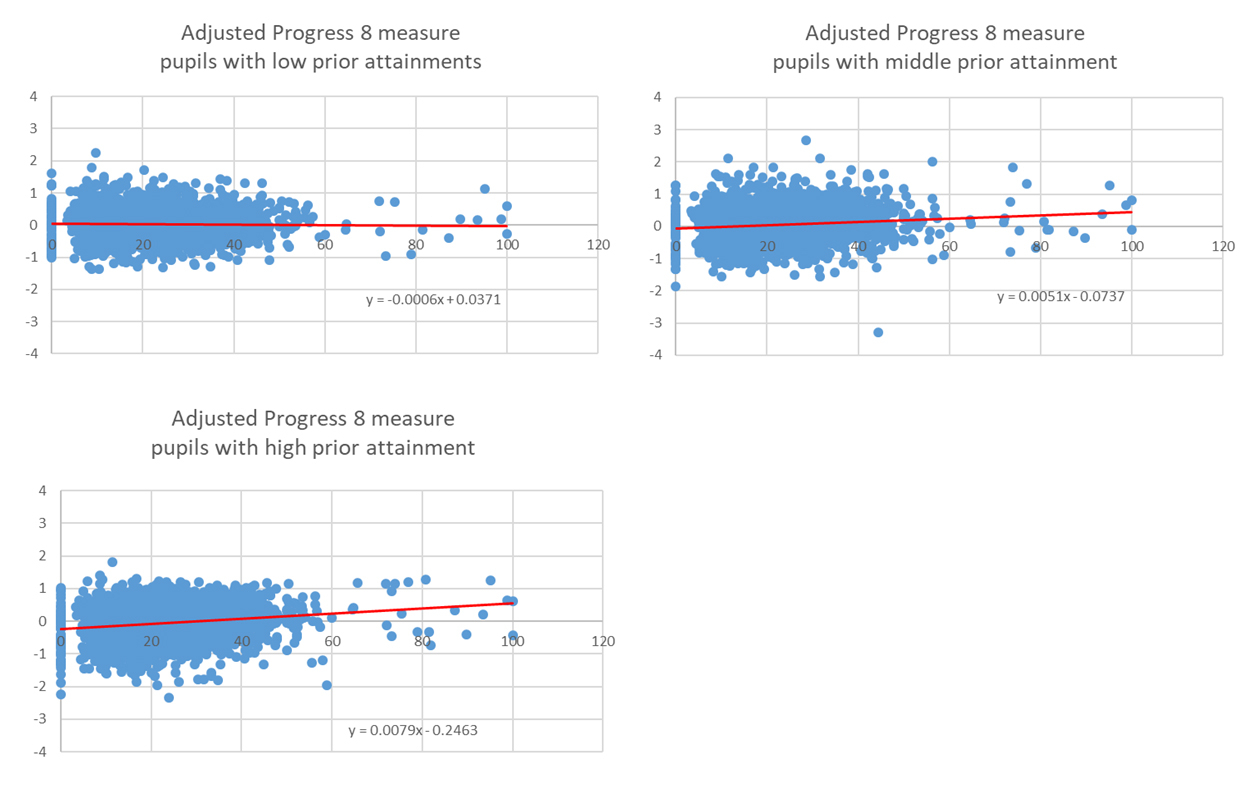

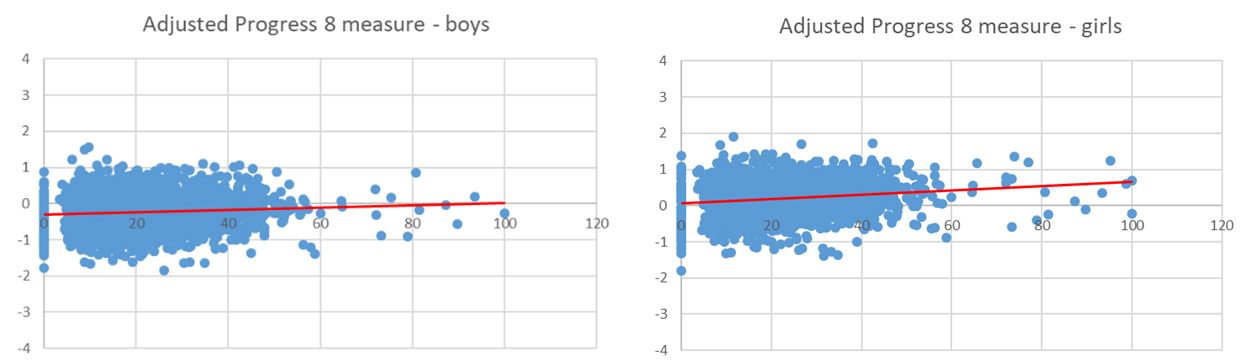

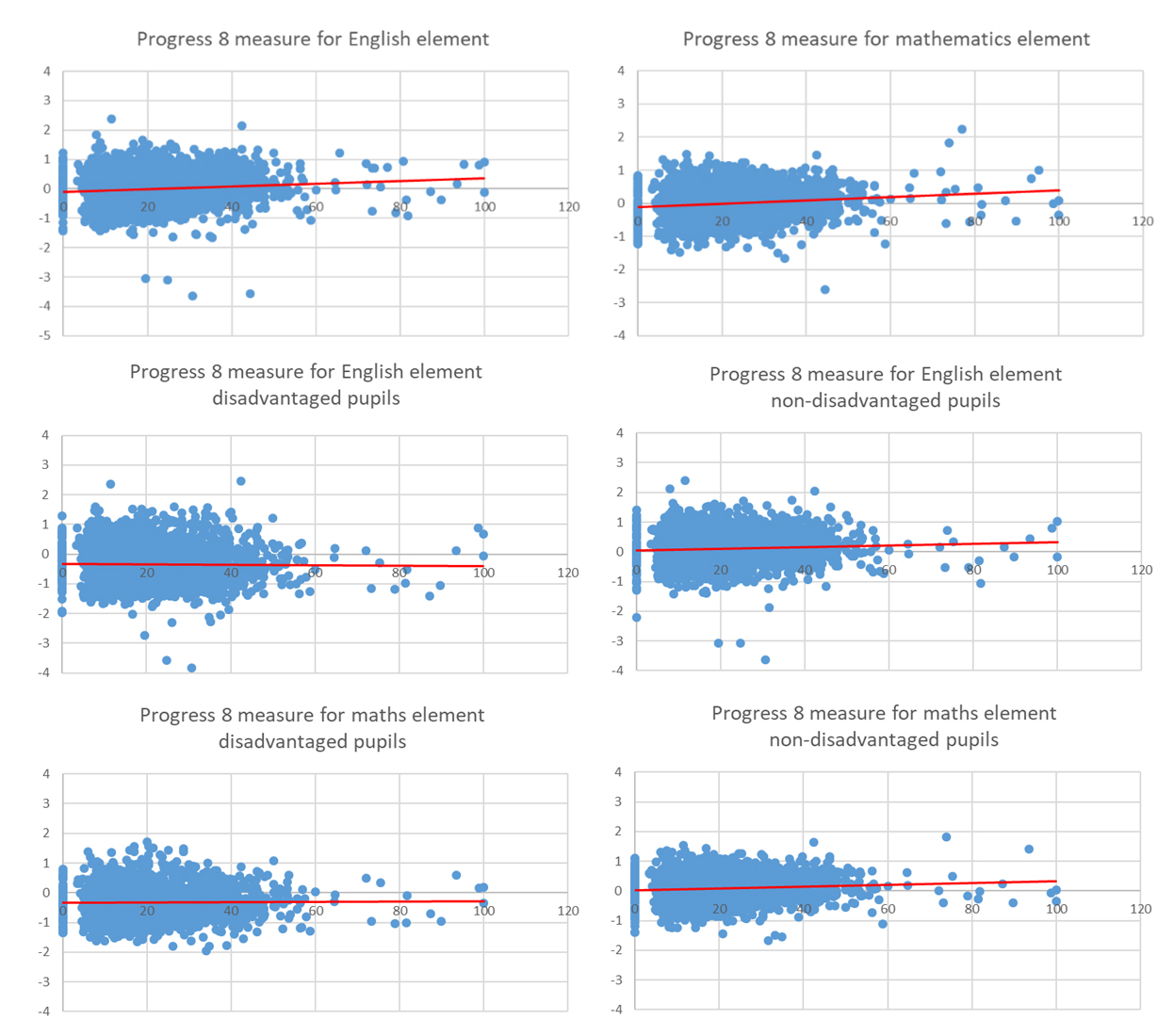

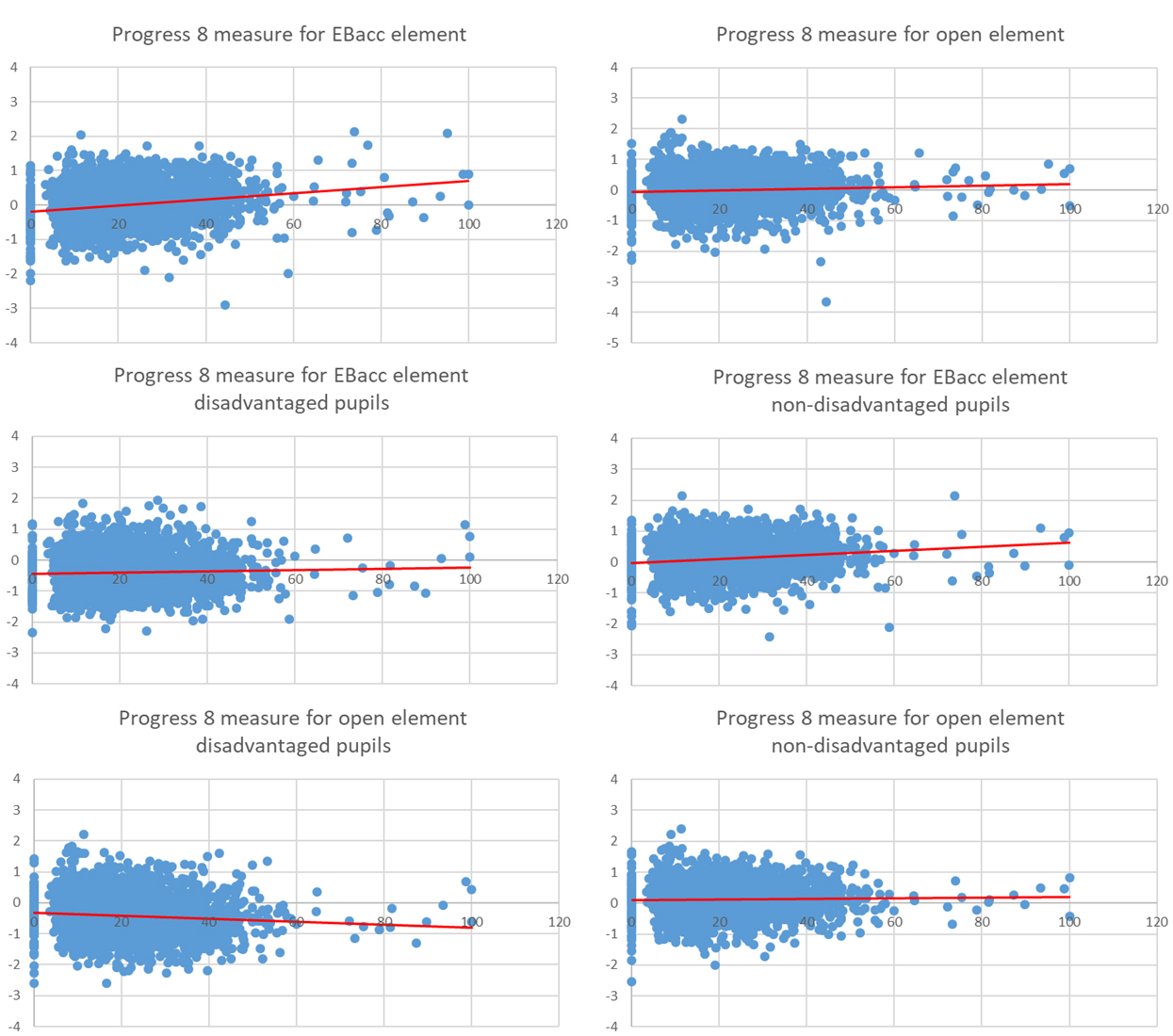

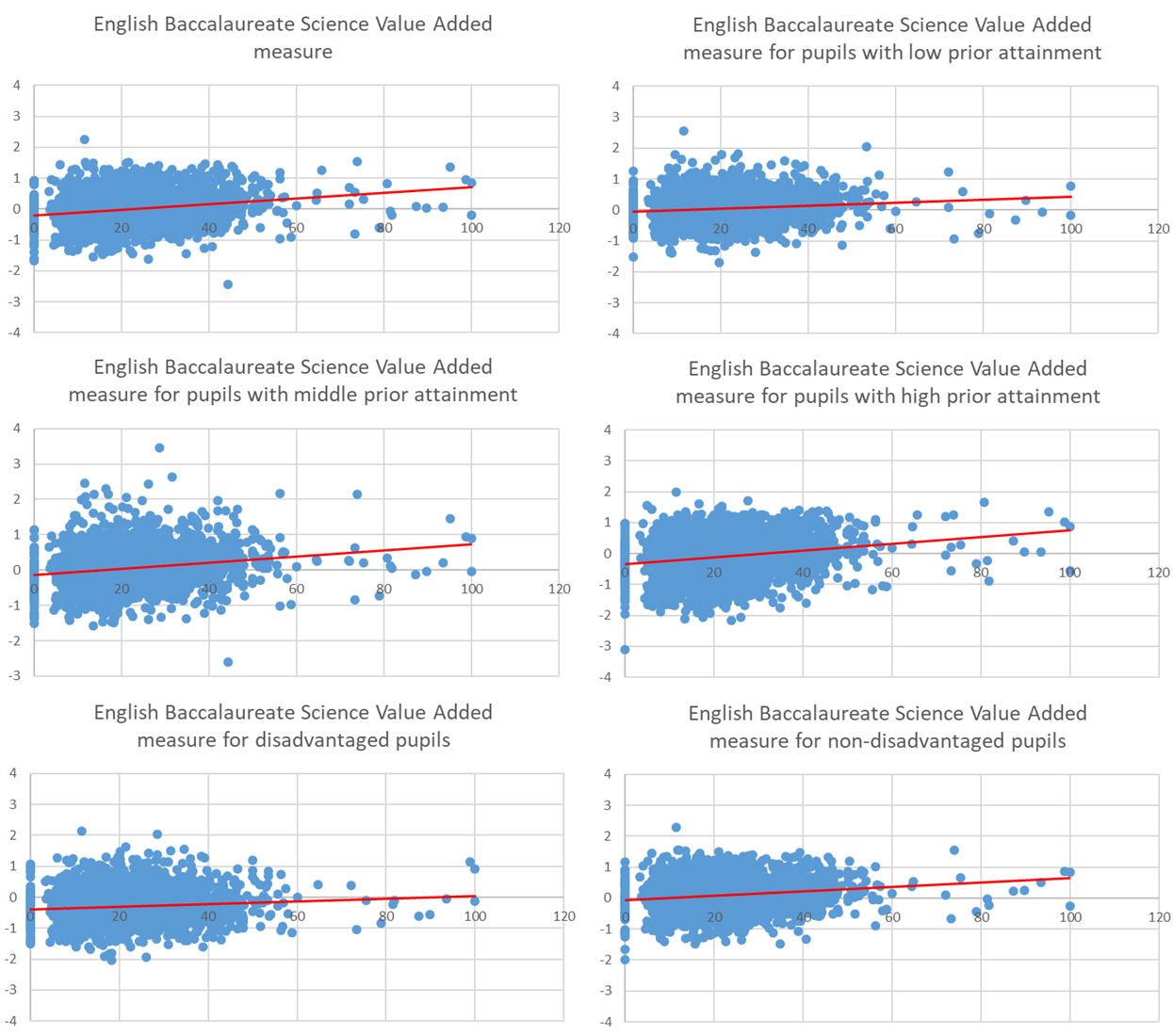

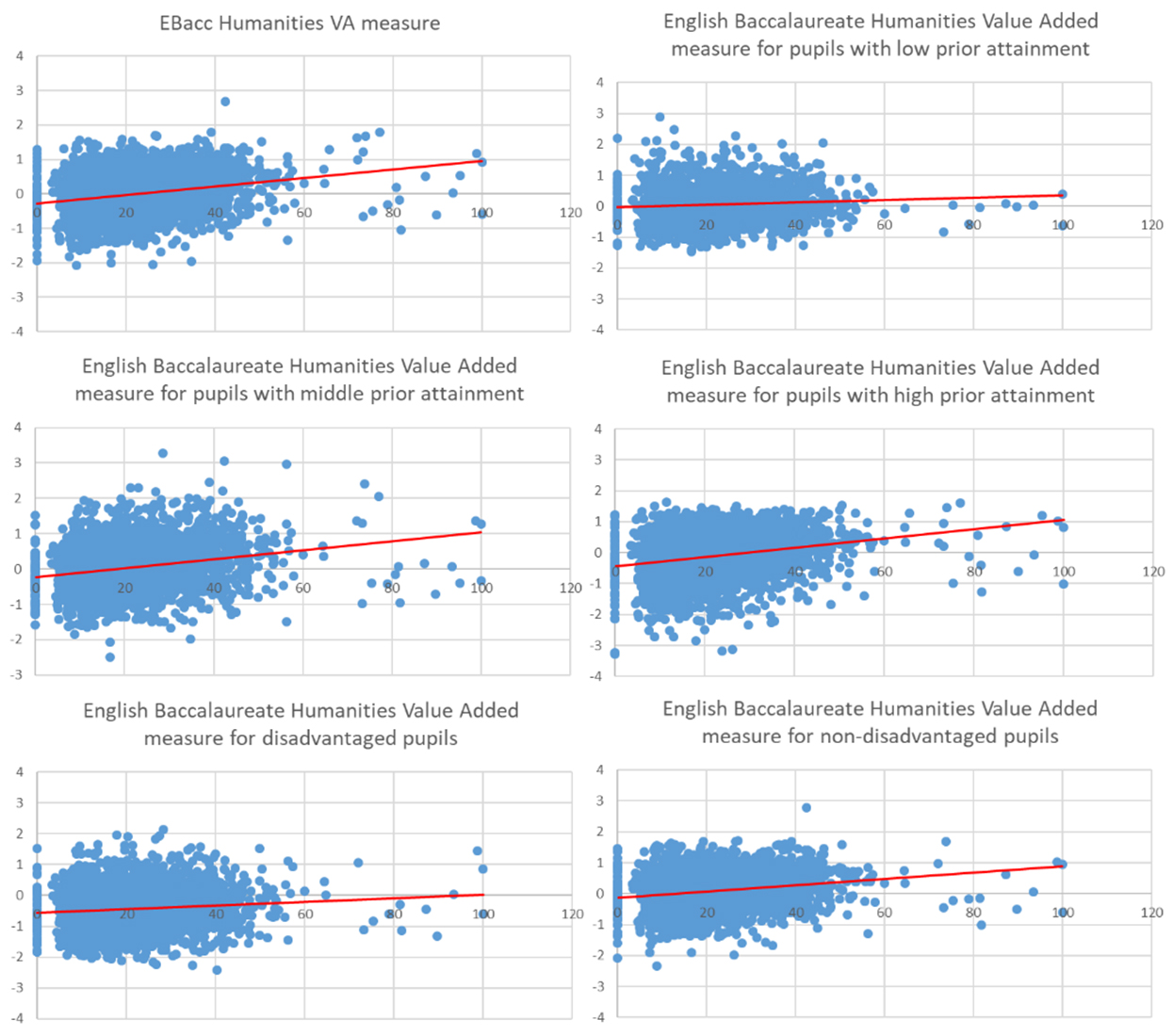

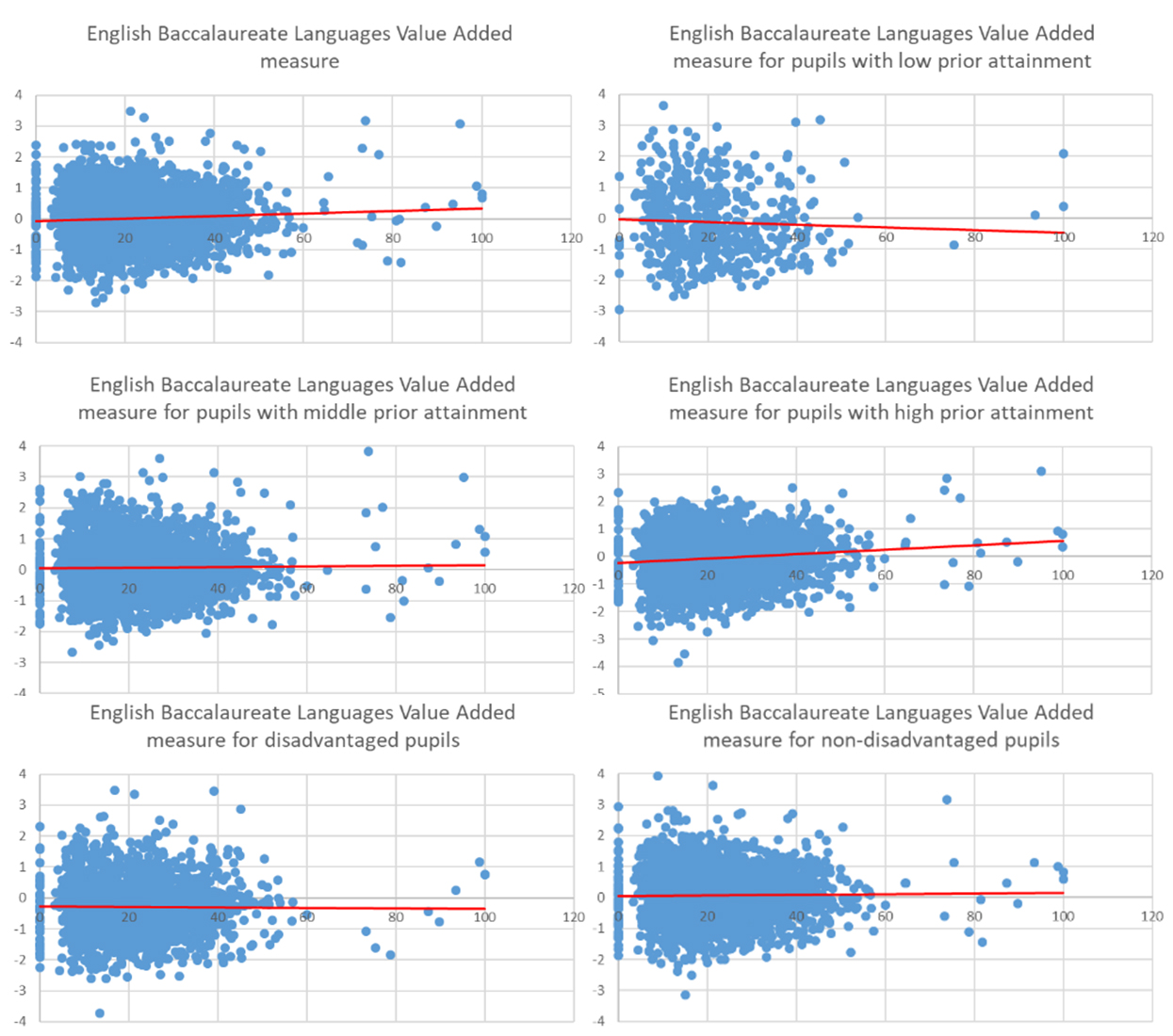

The benefits or otherwise of part time teachers to the progress of students is a vital part of the conversation that needs to take place. I have taken data on the percentage of part time teachers in each school from the November 2017 School Workforce Census, together with the Key Stage 4 performance tables data that provides progress data in different subjects and for different groups of student. From this I have produced a number of graphs showing percentage of part time staff (as of November 2017) and Year 11 progress data (for Summer 2018). Where possible, the data has been adjusted for extreme scores. The data has to be used with caution in that we do not know who taught the students, but it provides a starting point of ideas for schools to discuss.

‘Split classes’ and deployment of non-specialist teachers

There is also information that should lead schools to consider what to do when they have a situation where classes need to be taught by more than one teacher across the timetable cycle, often (but by no means exclusively) due to accommodating part-time teachers. Heads of department might allocate the high prior attainment (HPA) students to a single teacher thinking they will benefit most from consistency. The data here appears to be telling us that the lower prior attainment (LPA) students and disadvantaged students are those who would benefit from more consistency. There is also possible evidence that HPA students may actually benefit from a variety of teachers.

Science staffing at Key Stage 4 should also be considered. Recently there has been an increase in the number of schools where science classes at Key Stage 4 are taught by a single teacher (usually a specialist in only one of the three science subjects) for up to 10 hours a fortnight (across all three science subjects), with the driving force being the ease of maintaining accountability for results. The data here suggests that schools who have embarked on this policy should analyse their data to see what the effect is and work with other schools who have followed a different path to work out the best model for student progress and attainment.

How a school uses a non-specialist teacher in a core subject area is another area worth consideration. Often these staff teach classes of students with lower prior attainment, or in KS3. Schools should consider whether another way of utilising these teachers could be, for example, to give them one lesson per cycle with a HPA group and teach standalone units of work.

Implications

The data suggests that the effect on LPA and disadvantaged students is different from the effect on HPA and non-disadvantaged students when it comes to the proportion of part time teachers in a school. In essence, the data suggests that being taught by part time teachers appears to have a more negative effect on the progress of LPA students and those who are disadvantaged. This bears out the rationale that some schools use in ensuring that the LPA in Year 7 are taught by a fewer number of teachers than their peers.

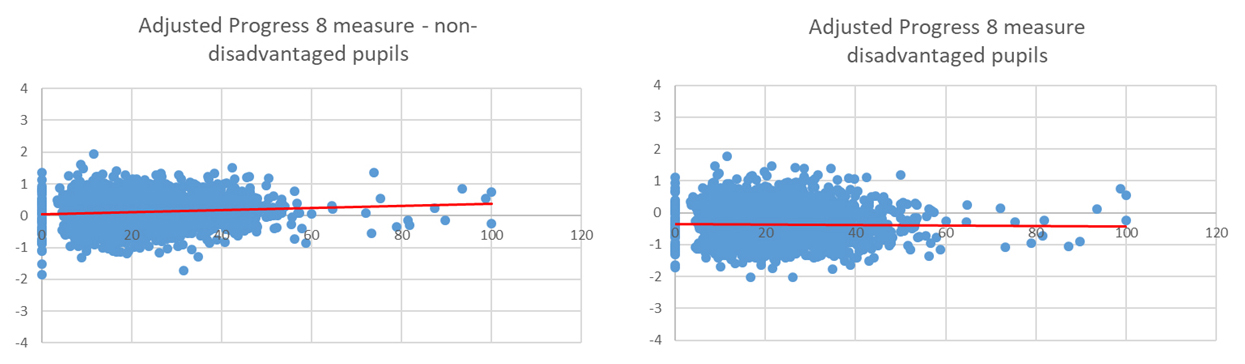

For each of the following graphs:

- the x-axis represents the percentage of Part-Time teachers a school had in the year the students were in Year 11

- the y-axis represents the Progress measure from Key Stage 2 to GCSE

Overall progress 8 measure

As we can see the trend line is positive, potentially indicating that having a greater proportion of part time teachers has a positive benefit on student progress, but it is not conclusive.

Disadvantaged/non-disadvantaged students

Comparing these two graphs is interesting. Firstly we notice the difference between the progress of disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students, but also the difference in the gradient of the trend lines. For non-disadvantaged students the trend line is very similar to that for all students, whereas the line for disadvantaged students has a negative gradient, indicating that, as the proportion of part time teachers increases, student progress decreases.

Prior attainment

Here we can see a marked difference between the graphs for LPA students and HPA students. The trend line for LPA students is negative, indicating that, as the proportion of part time teachers increases, student progress decreases. It is interesting to look at the data on all three graphs for schools with 0% part time staff, which gives a different message for LPA than the other 2 graphs, in as much as progress appears to be better for LPA students in schools with no part time teachers. It is also interesting to note that the gradient of the trend line for HPA is greater than that for middle prior attainment MPA, suggesting a stronger correlation between a higher percentage of part time staff and better student progress.

Boys/girls

Of note here is that the trend line on the girls’ data is steeper than that for the boys’ data, as well as the boys’ trend line being consistently lower.

Questions that schools might ask themselves, based on this data:

- which staff are part time, and in which subject areas do they teach?

- how do we plan for part time teachers?

- how flexible can we be as a school?

- how flexible are our part time staff prepared to be?

- how many split classes (classes that are taught by more than one teacher over a timetable cycle) are there in our timetable?

- how do we plan for split classes?

- have we analysed the progress of students in classes taught by part time teachers, and students that have been taught in split classes?

- how many teachers do year 7 students encounter in a timetable cycle?

- how many teachers do Low Prior Attainment and Disadvantaged students encounter in a timetable cycle?

- how do we deploy non-specialist teachers so as to maximise student progress?

Subject progress

In the following sets of graphs the trends seen in the overall data are replicated, with there being a marked difference in the impact on progress of LPA students and that of both middle and HPA students. Similarly, the difference between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students is also consistently replicated.

English and maths

EBacc measures

Science

Humanities

Languages