Whilst thinking about writing this blog, I went back to Richard Skemp’s book, ‘Mathematics in the Primary School’, published back in 1989 and promptly disappeared down a rabbit hole. Several hours later, this quote stuck with me:

“If the processes of multiplying numbers of any size are learnt as mechanical rules, little understanding and no creativity are involved. Children are simply being taught to function mechanically like a calculator, and for getting the answer quickly and accurately, it is much better for them to use calculators.” Pg 80

Relational vs instructional teaching

Skemp is a great advocate of teaching relational maths rather than instructional maths. He describes relational understanding as knowing what to do and why and instructional maths as rules without reasons.

In the first chapter, he provides arguments for both, and refers to the effect that assessments, tests, and exams, have on teachers’ decisions on how to teach. The vast majority of tests focus on getting the right answer and have a pass mark, so how the answer is achieved is not considered. This means that if the answer or process can be correctly recalled, the correct answer can be achieved with little or no understanding.

Skemp also lists ‘time’ and ‘an over-burdened curriculum’ as other reasons why teaching for relational understanding is a challenge.

Nearly 35 years later, have things changed?

I would argue yes, and no.

The need for relational understanding

I think we have a much better understanding of the need for relational understanding. Schemes of work that support teachers to deliver the curriculum are designed to support learning for understanding, but the tests children sit in maths are still about right and wrong responses, and how those answers are achieved is less considered – mainly because this is very difficult to do in a written test.

That means teachers are sometimes torn - I know I was.

I regularly asked myself the question, ‘Do I teach this properly or do I teach this in a way that the children will remember the rules and achieve the mark in the test?’. For some children, this doesn’t impact their progress but for others, especially those that struggle with maths, it does.

Without understanding what has been taught previously, it is very hard to progress, make connections, and learn new content.

Another challenge listed by Skemp was time. Teachers are still time-poor, and we still have a very full curriculum. So how do we support children to understand maths better, in manageable ways, to help create links and include creativity?

Finding a balance

In this blog, I can’t provide a solution for the whole of the maths curriculum, but I can offer a simple idea that will help when teaching and learning times tables. The Year 4 Multiplication Tables Check is one of those ‘hoops’ that our children must jump through and is purely about regurgitating a right answer. Many teachers are not fans of this assessment, and I think Skemp’s quote sums up why.

I do think it is very important for children to learn their times tables so that they can use and apply their learning. I meet a lot of children who can give me the answer to a multiplication fact but then can’t make connections to other learning (when trying to simplify a fraction, for example). I also meet a lot of children who, due to not having quick recall of times tables facts, feel they can’t do any maths.

Preparing for the Multiplication Tables Check (MTC)

In Rachel Brown’s blog Put your school in the driving seat for the Year 4 Multiplication Tables Check | HFL Education, she provides great advice on how to teach times tables in preparation for the MTC. I am going to drill down further and specifically look at those tricky facts. Many of the times table online practice sites, can provide a ‘heat map’ of children’s scores for the different facts. This means that you can pinpoint which facts are less secure. But to be honest, I am sure you could list the specific facts you know children find hardest to learn.

Once we know which facts need extra rehearsal, practice can be introduced.

Practice and rehearsal to make meaningful connections

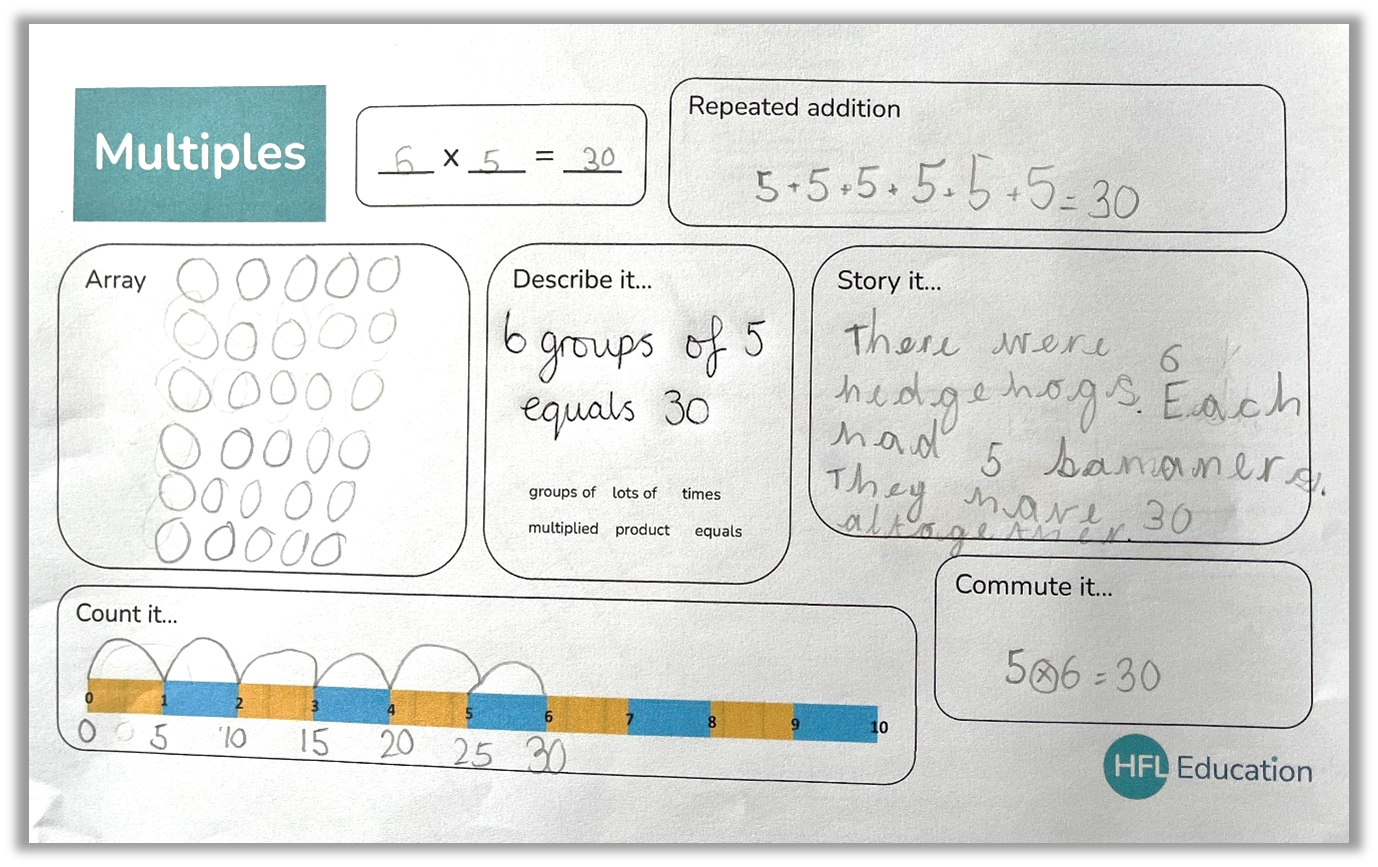

The idea of a practice scaffold is to rehearse a multiplication fact in multiple ways, to make connections between different models and language, and to build relational understanding. They also provide opportunities for overlearning. Once the learning rehearsed within the scaffolds has been taught, the children should be able to access them independently.

A practice scaffold example:

The starting point provided by the teacher could be the calculation. However, it doesn’t need to be. In the example above, ‘Describe it…’, is the starting point.

The rest of the scaffold is then completed by the pupils, who must make connections to various representations of the calculation. This draws upon the CPA approach with the option to include a ‘build it’ element.

Variation in representation on the scaffold

Repeated addition

Understanding multiplication as repeatedly adding equal groups is essential. ‘Timesing’ is a common shorthand for this.

Array

The array, drawn or built, is a visual area model. When creating the array, you are showing the space it covers. This is a link missed by many. The array also clearly shows the commutative nature of multiplication.

Count it…

The linear counting stick model shows that an equal group is being added each time, alongside repeated addition and the array model. Using a dual-coded counting stick enables a clear link to be made to multiples, for example, “the 6th multiple of 5 is 30”.

Commute it…

Knowing that when you learn one times table fact, you actually gain two, is a lovely ‘secret’ I enjoy exploring with children when commutativity is first introduced. The array clearly shows that the product stays the same whether you multiply the number of rows by the number in each row (6 groups of 5 in the example) or multiply the number of columns by the number in each column (5 groups of 6 in the example). Practically building the array with multilink cube enables you to physically turn the array to show this.

Describe it…

Interpreting the language of mathematics is often a stumbling point for children. In this box, vocabulary or sentence stems can be provided and if the scaffold is used repeatedly, children should be encouraged to vary how they describe the calculation.

Story it…

This box allows children to do something we very rarely do, which is require them to contextualise the calculation. Children regularly solve contextualised problems but here, they have to create the context themselves. It could be in the form of a question with a solution (as in the example), a question to be solved or a statement. Many children find this tricky but once they get into the swing of writing them, it is a great opportunity for them to be creative.

Adaptations for even deeper thinking

Practice scaffolds can be altered, depending on the age and confidence level of the children. You might want to include inverse facts, for example, so a box labelled ‘inverse’ or ‘fact family’ could be added. Space could also be included for building a model.

For older students, the language of factors could be included. This could be further extended through scaling and understanding of related facts such as 60 x 500.

Another box I sometimes add is titled, ‘Tell me something else…’ This allows freedom for children to be as creative as they wish.

Repetition is key

The practice scaffolds are designed as an overlearning task so need to be done repeatedly. Once the structure of how to complete them has been modelled and taught, they can be completed independently. I have seen them being used as an early morning task and as part of homework.

The same practice scaffold can be used multiple times to either practice the same calculation – for this, vary the starting point – or for different calculations that you know are the tricky ones. Every child in the class can have the same scaffold, but you might personalise the calculations to practise.

Some schools I have shared these with have them in a plastic wallet and the children complete the scaffold using a white board pen to reduce printing and make repetitive use simpler.

Maths as a tool for life

As Skemp said, a calculator is the best tool for mechanically solving a calculation, and nearly all of us carry one around in our pockets – despite my teachers telling me otherwise – so we don’t need our children to robotically recall facts.

We want them to know their times tables but in a way that encourages them to make and see connections, so they can use and apply the learning across their maths curriculum, not just to be able to jump though one of the many hoops put in front of them.

Is the teaching and learning of times tables a key focus in your school?

The HFL Education Primary Maths team can work with you in school to develop the teaching and learning of multiplication facts through The Multiplication Package.

Find out more about the HFL Education Curriculum Impact Packages: