As educators, we are very familiar with the term ‘feedback’. Its plays a vital role in our own CPD and providing feedback – in all its forms - takes up a large proportion of our time. Feedback can be transformational. We know that “providing feedback is well-evidenced and has a high impact on learning outcomes,” (Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), T&L Toolkit but we also recognise that when “Done badly, it can even harm progress.” (EEF, Teacher Feedback to Improve Learning)

Before we explore forms of effective feedback in the writing classroom, let’s remind ourselves of the purpose of providing feedback: to move learning forward. This blog by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), provides a series of recommendations to support teachers and leaders to ensure that pupils are making effective use of the feedback they receive. As Dylan Wiliam states, “no matter how well the feedback is designed, if students do not use the feedback to move their own learning forward, it’s a waste of time. It is essential that the feedback is productive.” (Helping or Hindering? 2014)

In classrooms where writing is valued, there can be a beautiful synergy between the joy of writing and the art of providing reflective, motivating feedback. When used thoughtfully and constructively, this feedback has the power to inspire, motivate, and guide young writers, contributing to improved self-esteem and the development of writer identities.

The joy of self-expression

“Writing is something that is both personal and intensely social, both analytical and emotive." (Young & Ferguson 2021)

If writing is a form of communication and expression, then it is our job as educators to ensure that our young writers feel safe and motivated to leave a little piece of themselves on their page. The art of providing feedback to writers is being able to mentor and guide them to make improvements, whilst allowing them to maintain agency and autonomy so that they can still feel a sense of ownership and responsibility. Writing is a powerful human act, and it is imperative that our feedback remains human too – whatever form it is delivered in.

Seeking feedback in supportive settings

Feedback is most valuable when it provides actionable suggestions for improvement. Instead of simply pointing out errors, offer guidance on how to address them and provide a purpose for this.

We can begin by shifting the spotlight from just the final product to the entire writing process. Acknowledge the effort put into generating ideas, planning, drafting and revising. Highlight the value of revision as a tool for improvement, reinforcing the idea that writing is an evolving craft that requires time and dedication. Use feedback as an art that shapes the budding authors of tomorrow.

Do children know that real authors add, remove and substitute words and full sentences all of the time, and often as a result of feedback from others? Do they see making improvements as a positive step to improving written outcomes and readability for a real reader? And as a result of all of this, do they seek feedback themselves?

In all its forms, feedback should be delivered by a trusted source, with ample time and opportunity to respond and use the feedback provided.

“I’m ready for my feedback!”

“Feedback is what happens second, after high-quality teaching and careful selection of assessment tasks that reveal how well students have understood the learning.” (Dylan Wiliam, 2021)

High quality instruction and effective formative assessment will reduce the work that feedback needs to do. First, it may be worth evaluating the impact of your writing curriculum. This blog on what makes an effective writing curriculum will help you to make further considerations.

Let’s consider how we can use timely and specific feedback for writing in the classroom:

For you, my reader

When writers have a clear goal in mind, it enables them to reflect on their intent and effect throughout the writing process. Do children know who they are writing for? Do they have their audience in mind throughout?

When the answer is yes, this can enhance engagement and motivation hugely. Whether it’s a friend, teacher, parents, or a broader audience, having a specific audience in mind gives young writers a sense of direction. The feedback we provide should also relate to this notion.

Evidence shows that feedback is less effective when it is about the person. So instead of using generic comments such as, “fantastic writing!” or “you’re a natural!”, let’s relate this feedback to the impact the writing has on their reader. Be specific about what you appreciate in their writing. Highlight specific sentences, phrases, or details that stand out. For instance, you might highlight a specific area and say, “I love this vivid description of the setting in your story—it really transported me there,” and give specific examples.

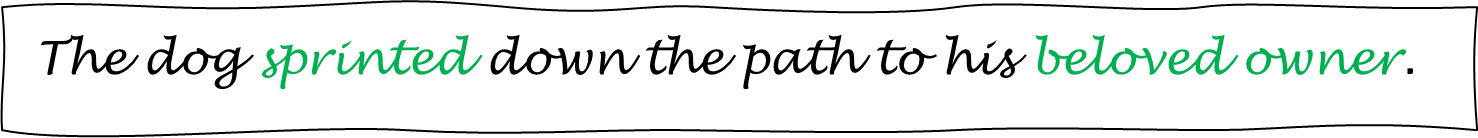

When improvements or adaptations are required, provide a purpose here, too. For example, if the child wrote:

Always start with a specific piece of positive praise – “I love how you have thought about giving your reader information about how the dog ran and where it was running to. This is essential.”

Then, provide one clear suggestion that guides them to improve further, with their reader in mind:

“How could we develop this even further to help our reader understand the reasons for the dog’s urgency and speed?" Or “Which words - verbs/noun choices - could be tweaked here to help the reader understand and empathise more?”

“Fantastic! Now your reader will really understand the dog’s reason for sprinting. We understand him more and can relate to his excitement.”

Keep reading for more about this ‘conferencing’ approach and other feedback approaches.

We’re live in 3, 2, 1…

Live marking has recently been deemed by many as the more superior form of ‘marking’. Whether this feedback is delivered as a whole class, with target groups or individuals, in written form or verbal, it can allow us to address misconceptions as they arise and adapt our teaching as necessary. In addition to reducing teacher workload, live marking or ‘fast feedback’ is considered a useful tool for quick wins. However, the EEF advises that “teachers should judge whether more immediate or delayed feedback is required (EEF Feedback Recommendations, 2021) to ensure that feedback is personalised and impactful”.

Live oral feedback can allow pupils to make impactful changes or reflect deeply as they write in the moment.

Many schools implement pit stops/mini plenaries within whole-class feedback to provide opportunities for whole-class improvement. Here, children can check and ‘live mark’ themselves during the writing process.

On the contrary, delayed feedback might provide pupils with time away from their writing. Returning at a later point may help them to evaluate their initial choices more effectively.

Continue to consider the timing of your feedback and when it is most impactful for individual learners. Ask yourself: Is it moving learning forward? Is it addressing the learning gaps that your pupils have?

Is it serving the needs of struggling writers?

Conferencing

Conferencing can be used within, or away from, ‘live marking’ in the moment. It provides a short and supportive moment for teacher-pupil dialogue. So, what might a ‘conference’ look like?

- First, put the writer at ease. Start with simple, open-ended questions that prompt effective dialogue.

“How’s it going?” “Tell me about your writing so far!” “Is there anything you’d like to read aloud?” “Anything I can help with?” - Encourage them to read their writing aloud. You can then ask more specific questions to prompt the writer to think about the impact on their reader. “What did you want your reader to imagine/feel here exactly?” “I felt quite fearful reading this bit. Was that your intention? How could we add to this emotion?”

- Using the knowledge gained from the discussion, provide one piece of really clear feedback - based on the success criteria - for them to implement.

- Make them feel proud and successful – be specific and human throughout.

If pupils require further support (perhaps with the transcriptional elements of their writing) this can then inform your assessment and future feedback or support.

Read more about conferencing over at the Writing for Pleasure Centre.

Written feedback

Whether in marks, scores, comments or through use of tools such as sticky notes and speech bubbles, its success will vary depending on when and how it is delivered and of course, when children have time to act on it. Remember: is it timely? is it specific? Read more about this in the EEF Guidance Report.

Here are some impactful examples of written feedback that you may wish to try with your writers:

“You can’t edit a blank page”

True – but a blank page can certainly be useful for providing feedback during the drafting process. Some teachers find that leaving a blank page next to pupils’ writing is beneficial for recording personal notes and peer/teacher feedback. This is particularly useful if you didn’t have time to feed back verbally during live marking and/or want to provide some focused suggestions in the form of sticky notes or when you are away from the child. Remember to follow this up with dialogue and give the writer time to respond.

Build independence with signpost marking

A simple arrow, highlighted area or asterisks in the margin can point children in the right direction to areas that may need a further look. Again, time and further dialogue may be needed here too.

Box marking

A simple highlighted box around a small, focused area within longer pieces of writing can be used to provide specific and focused feedback during live marking moments or even conferencing. Within this box, you may guide writers to make compositional or transcriptional improvements. Using the knowledge gained from this focused feedback will support them when editing or proofreading the rest of their piece independently or with a partner.

Peer perspectives

Foster a collaborative writing community by incorporating peer feedback into the process. Encourage students to share their work with classmates, promoting a culture of constructive critique. This not only provides additional perspectives but also cultivates a supportive atmosphere where students learn from each other's strengths and areas for improvement. However, this needs to be planned carefully within supportive environments, so children feel safe and successful taking part.

Like any form of teaching, children need to be explicitly taught how before having some time to practise. Prepare them by:

- Walking them through it: model what effective peer discussion can look like and help them to understand the purpose of successful collaborative dialogue

- Getting them reading their writing aloud to their friend

- Maintaining agency so learners see feedback as providing ‘suggestions’ for correction or improvement

- Providing question prompts that allow their peers to elaborate on their thinking and justify their choices

- Using speaking frames to guide their conversations: focus on specific praise and a specific area for improvement (linking back to the effect on the reader)

- Being positive and specific!

- Allowing the writer themselves to make any necessary amendments – there’s no scarier feeling than seeing someone else’s red pen heading towards your precious writing

- Making use of resources such as sticky notes if written feedback plays a part in peer responses

- Trying working in groups of 3 or 4 instead of sticking to pairs

- Providing ample opportunity for reflection and evaluation.

It is important to note that peer feedback is not a replacement for teacher conversations. Feedback should be inclusive and immersive and when children know that it is a supportive component to improvement, this will hopefully remove the fear factor and put them at ease having these discussions.

Explore the EEF’s teaching and learning toolkit to read more about how other high quality, carefully planned interactions between pupils can contribute to success.

Read about how this Year 6 class sought and received feedback from a range of esteemed experts. (The Writing for Pleasure Centre, 2022)

Pupil voice

A good place to begin with developing feedback for writing in your school could be by conducting a pupil voice questionnaire. Ask your young writers, “what do your friends think about your writing?” and “how do you know?” or “tell me about a piece of writing that your friend wrote.” This will give you a real sense of whether peer feedback is actually happening, if it is happening effectively within an authentic environment and whether children see themselves as real writers.

Showcase their work

Celebrate the achievements of young writers by showcasing their work. Whether it's through classroom displays, school publications, or sharing with their readers, giving young writers a platform to share their creations boosts their confidence and reinforces the value of their efforts.

In the world of writing instruction, feedback is not about correction - it's a conversation that shapes the next chapter of a student's literary journey. By celebrating strengths, providing specific guidance, and fostering a growth mindset, teachers can inspire a love for writing and empower their students to become confident and skilled authors.