As a professional in the education sector for many years, it never ceases to amaze me how, once you are made aware of a ‘new’ initiative to address an issue, your focus of attention is inexplicably drawn to its potential influence. Over the years this has, for me, involved multifarious ‘fads’ that are ‘in vogue’ for short spaces of time. They become ephemeral as impact is minimal or they are based on subjective research.

The opposite of this situation has had such a profound impact on me recently, both professionally and personally. I am drawn to share my experiences and ideas in a wider context through the writing of this blog. I will separate it into three parts. Part 1 will provide an overview, rationale and intended impact. Part 2 will focus on ‘what that actually looks like’ in practice in Primary Schools and Part 3 will explore specific examples of the implications of what happens with young adults when their needs are not met early in their education.

Rationale

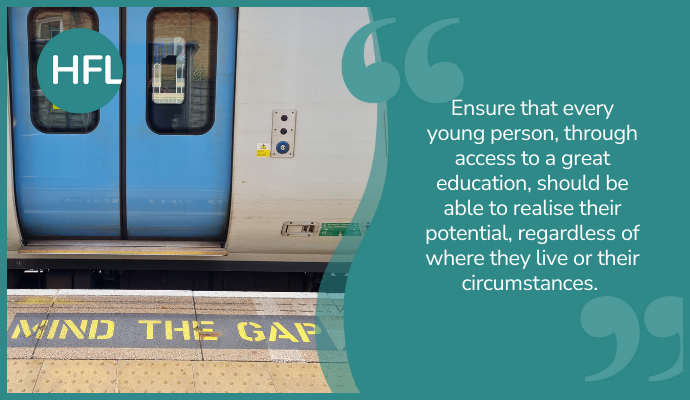

Led by Rachel Macfarlane, our overarching purpose at HFL Education is to ‘ensure that every young person, through access to a great education, should be able to realise their potential, regardless of where they live or their circumstances. Their education should be free from barriers presented by a lack of equality, diversity, and inclusion’.

As a Primary Maths Adviser, a key part of my work focuses on the removal of any existing and potential barriers to learning. Within this, ‘barriers’ can sometimes be unintentionally introduced across the range of children’s needs from all prior attainment points. This will be explored in detail in Part 2 of this blog.

Influencers

HFL’s Education Services Team continues its focus upon meeting the needs of disadvantaged and vulnerable children. This has involved engaging with nationally recognised educationalists. Dr Dan Nicholls’ recent input has had a profound effect on my thinking and subsequent actions. Especially with regard to the theme of ‘belonging’ and its associated barriers. This includes heightened understanding of ideas such as ‘invisibility’, ‘disconnection’, ‘trapped by circumstance’, ‘security of a far greater equity through education’ and (linked to the title of this blog) ‘giving individuals what they specifically need and seeking to close the growing chasm between ‘those that have’ and ‘those that have not’ and ‘the curriculum as a lever’.

I am not alone in my thinking. A recent blog by Kate Kellner-Dilks explores the whole curriculum as being ‘The moral imperative: creating a curriculum that develops identity, broadens horizons and enables success for all’. And in her recent and insightful blog, Nicola Randall asks the question ‘How can we advantage the disadvantaged?’ and states ‘…a child who has experienced economic hardship at some point, may not have developed a deep sense of self, built up over years of making meaningful connections with others and so do not feel that this community, this education system, is for them’.

‘Belonging’ (from both a professional and personal perspective)

I have been influenced by the collegiate approach within HFL. This has enhanced my thinking even more profoundly and led me to reflect on situations and circumstances in both my professional and personal domains. Within those, I recognise that conditions outside of the academic curriculum have had significant impact. These include instances from roles as a teacher and a leader, including being the Designated Person for Safeguarding and Professional and Personal Well-Being Lead, and as a child and father:

- a boy in Year Five, whose father was a doctor and mother was a solicitor trashing the classroom

- children hiding in various locations around the school

- a girl in Year Four who was constantly looking out of the window as she was concerned about what state her alcoholic mother would be in when she went home

- following a boy through a South London town centre (whilst in constant contact with the police) who had escaped from school to visit his estranged sister who was in another school as a result of domestic abuse

- dealing with a stream of parents/carers who were about to be homeless – many of these families were living in one room

- providing food for children who came to school hungry

- discovering that for a group of recent arrived Romanian children, the curriculum was not fit for purpose (explored further in a blog here)

- finding out by chance that my son was lip-reading in Year Two as he was deaf in one ear

- overcoming my own profound stutter/stammer during my time in Secondary School with multifarious strategies – which is almost resolved but still apparent on occasions – (this will be explored further in Part 3)

In all these situations, the personnel had different ‘belonging’ needs and either adapted to the situations as ‘best they could’ or, at breaking point, implicitly ‘cried’ for help. One incredibly challenging situation was attempting to address gang violence and its associated racism that was having a severely negative impact in a school in a London suburb.

In a recent meeting at HFL Education, David Cook referenced our ‘sphere of control’. We have control over the content of the curriculum, what we place emphasis upon, and also upon how we deliver it.

We, too, can influence the culture within the school. Both must meet the needs of all. There be may other issues outside of the curriculum to which we are not in control, and this may involve situations as dramatic as I have shared here. There could potentially be issues that affect a child’s understanding of belonging, or of not belonging; and this needs to be addressed. It can only be achieved through schools ‘getting to know’ each child as an individual to ensure that their needs are met and this ongoing process needs to be an integral part of the curriculum.

Dr Dan Nicholls refers to this as a ‘call to arms’: ‘Our collective endeavour, is to use education to illuminate and bring more colour, to more lives. It is through our leadership and in teams, that we can unswervingly focus on our best levers, teaching and culture to bring light to this darkness and to say, “yes, you do belong.”

In her wonderful blog, (Part 1 and Part 2) Kirsten Snook, when referring to reading and disadvantaged children, uses the analogy of: ‘Think of the difference between having the stress chemical cortisol flooding the brain and body rather than the ‘feel-good’ factor of serotonin’.

How powerful would it be to have that scenario as the ultimate aim to enable a sense of belonging for all and thus removing all barriers?

Moving forward

The title of this blog (Part 1) refers to ‘Mind the Gap’. In this instance, I am not referring specifically to the gap in academic progress and attainment but more to the combined process of allowing ‘access for all’ children, which are inseparably linked, of course. I will use the analogy of alighting of a train to explain the intended outcomes and associated challenges.

On a recent train journey, it struck me that the doors providing the access to the destination are not initially in your control. As you arrive, you receive the following message: ‘We are approaching your destination. The doors will open automatically on the right-hand side. Please ensure that you mind the gap and take all your belongings with you. Have a safe journey’.

For me, this is figuratively similar to the ‘access’ gaps:

- the doors are access to the curriculum via a journey – different starting points and personal circumstances does not guarantee automaticity of access

- access needs to be rapid or there is risk of being locked out – lack of progress

- trusting the process is optional – reliability of content

- access can be confusing – personalised needs not being met

- being locked out with no access means another journey – disjointed path

- one person in control – relies on complicity

- personal belongings are similar but also different – backgrounds and societal situations can define needs

- some people stumble and fall when crossing the gap, despite warnings – insecure application

Ironically, all doors share this warning sign on the inside. Continuing the analogy of allowing ‘access for all’ through alighting the train, this makes me think it suggests that ‘If you do not fit in then please distance yourself’. Is this how children feel when they do not have a sense of belonging?

On the same train, there are these posters:

‘For many of the 1 in 5 disabled people in the UK, the attitude of others can make or break a journey. Remember, not all disability is visible. A little extra time and consideration can make a world of difference to everyone’s journey.

Look out for each other.’

‘1 in 5 people have a disability, and not all are visible, so think twice before getting frustrated and be kind to others while travelling.

Because everyone deserves a safe journey – We’re with you.’

These posters and associated dialogue speak for themselves when they are linked to the idea of ‘belonging’. The key realisation for me here was the link to values in society such as humility, accountability, collective responsibility, dignity, fairness, honesty, humanity, and individual rights.

These values should be an interwoven part of any curriculum and linked to the personalised needs of each individual child, where fostering a sense of belonging for children can create an environment in which learning can thrive. When learning feels open and collaborative, children feel safe to share ideas. They are confident in applying their knowledge or skills and are supported when they take a risk or even experience failure. When children feel like someone knows them and believes in them, there is a greater motivation to succeed.

There are often words and phrases in education linked to the gap such as ‘reducing’, ‘closing’, ‘diminishing’ or ‘removing’ it. Perhaps, in the 21st Century and beyond, the ‘gap’ will remain as societal, and other conditions mean that it exists and can be out of our full control. Our mission remains though. To enable all children to access and engage in rich learning and feel a deep sense of belonging in it. This will be explored further in Part 2 with the implications of not acting accordingly analysed in Part 3.